From Dolomites to No. 1: Inside Sinner’s Piatti Academy Path

At 13, Jannik Sinner left the Dolomites for Riccardo Piatti’s academy in Bordighera. A host family, high‑repetition drills, modular fitness, and a measured schedule built the base for his 2024–2025 surge to majors and World number one.

A 13-year-old leaves the mountains for a system

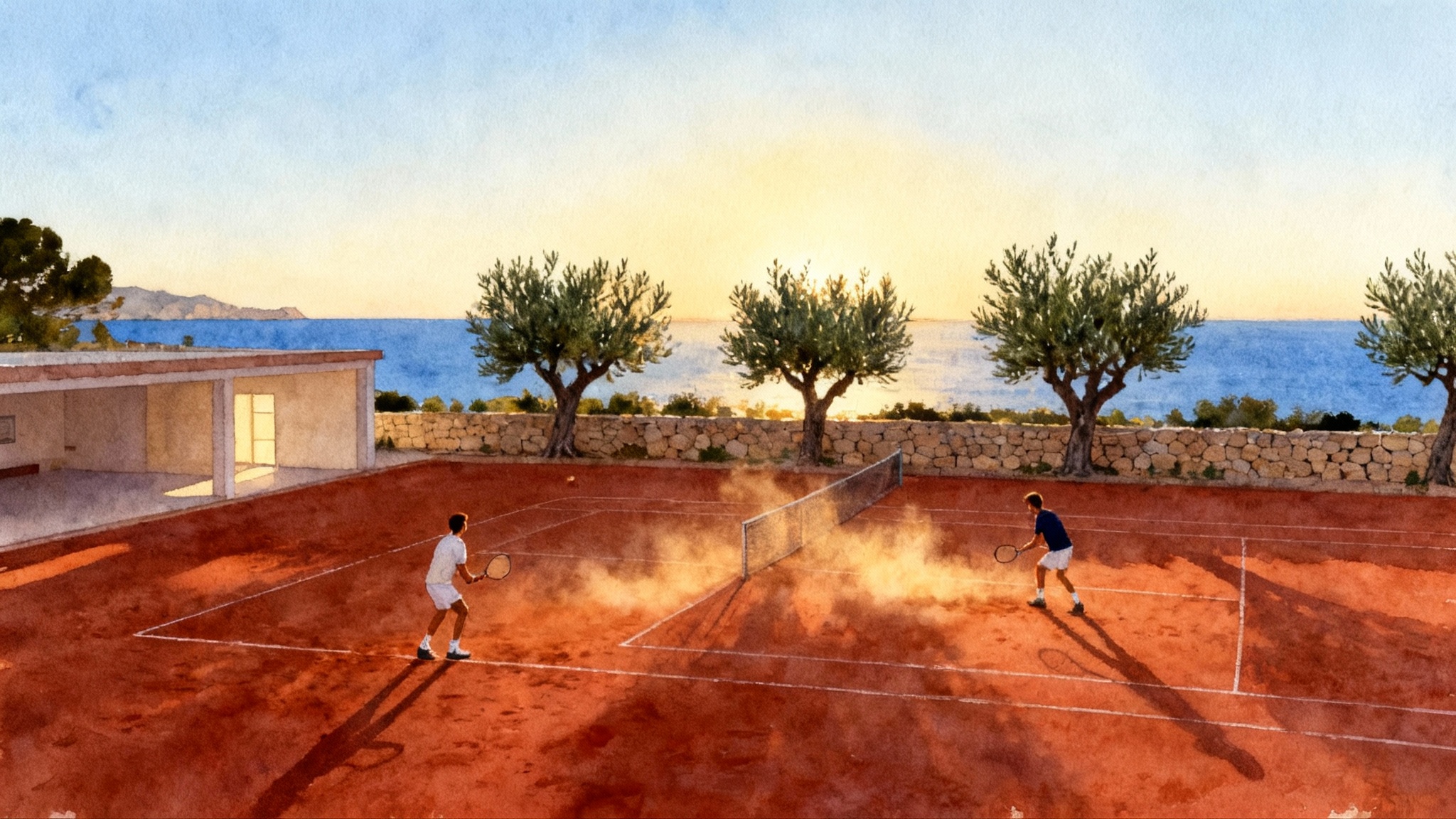

Jannik Sinner’s rise looks sudden if you only watch finals. It was not. At 13 he left Sesto in the Dolomites for Riccardo Piatti’s center in Bordighera. He did not move into a dorm. He lived with coach Luka Cvjetkovic’s family, took trains to junior events, and learned to be self-sufficient off the court as much as on it. That combination of structure and independence is the origin story of his resilience and reliability, as detailed in Piatti on Sinner’s first years.

The setup mattered. A safe home base, clear practice blocks, and a travel routine that Sinner could manage as a teenager created the habits you now see in tiebreakers against top five opponents: calm, consistent footwork, and decisions that do not wobble under pressure.

The Piatti method in plain language

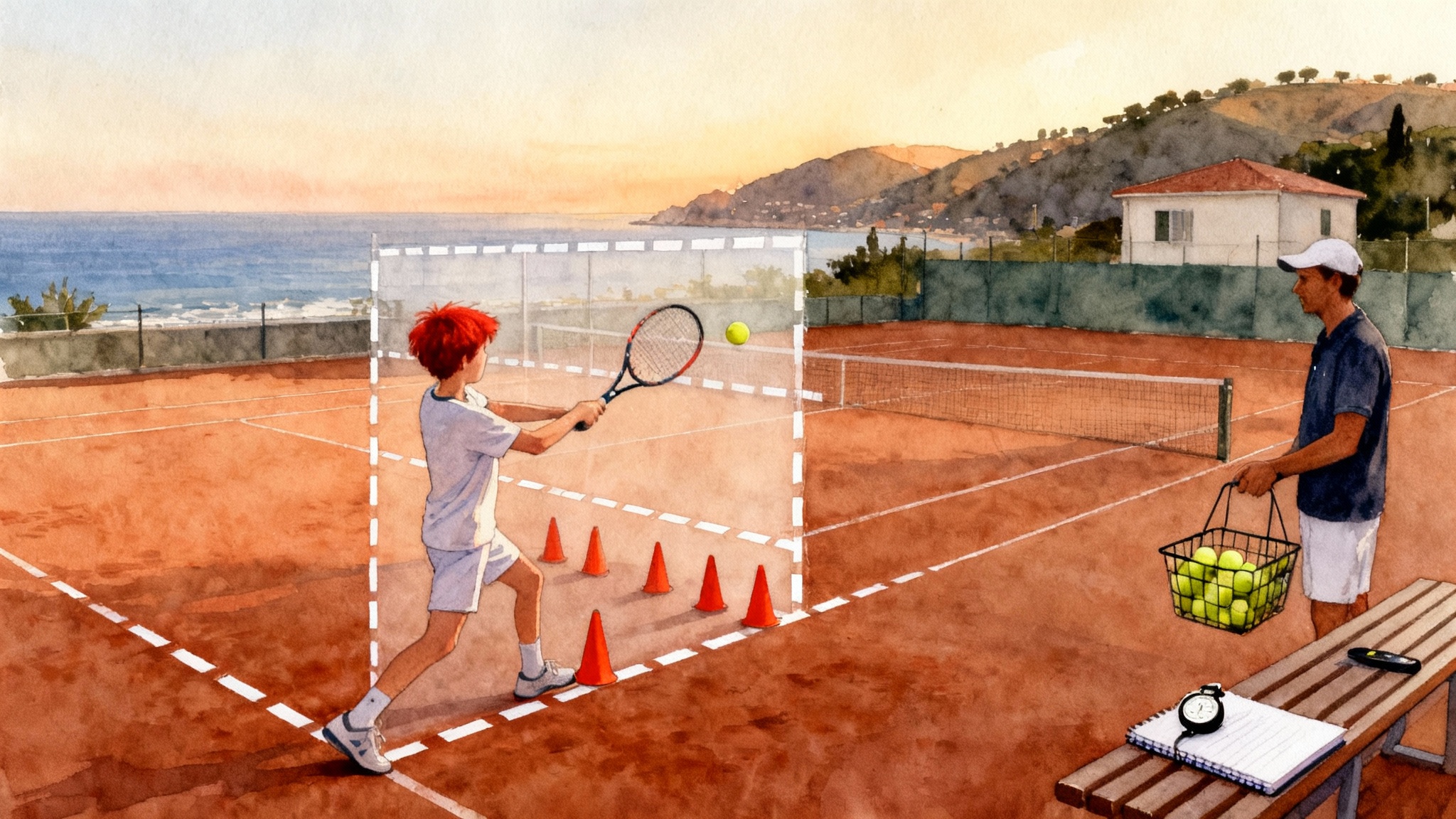

Riccardo Piatti’s approach is simple to describe and hard to execute: repeat the right actions so many times that they hold up at 5–5. He likes to build a player’s floor first, then raise the ceiling.

- High repetition with constraints: hundreds of balls through the same contact window, using cones and tape to narrow the target. The constraint forces precision without overthinking.

- Modular fitness: short, frequent strength and movement blocks placed between hitting to keep quality high. Instead of one long session that degrades technique, you see three micro blocks of mobility, core, and acceleration inserted around live ball.

- Measured tournaments: early on, fewer events than peers. More practice than prestige. Matches are chosen for learning, not for photos.

You can see similar sequencing in other elite paths such as Djokovic’s Niki Pilic Academy years and Alcaraz’s JC Ferrero Academy path.

Drills that turned into weapons

Backhand and return patterns

Watch Sinner’s backhand in slow motion. The racquet path is short, the shoulder turn is big, and the contact is consistently in front of the hip. That does not show up by chance. Two staple patterns in Bordighera made it automatic:

-

Two cross, one line: a live ball rally where the hitter must drive two crosscourt backhands deep to a taped zone, then redirect the third down the line without adding shape. The goal is to train the change of direction without a tell. The constraint is depth first, then line.

-

Short cross to line counter: the feeder plays a sharper, shorter crosscourt; the hitter steps inside the baseline and flattens line to a narrow corridor. The purpose is to own the redirection when an opponent gives angle.

Returns got the same treatment. Piatti likes three return stations per game: five points from a step behind the baseline, five with toes on the line, five from a half step inside. The receiver is forced to solve the same serve with different distances, adding the tiny forward hop you now see when Sinner anticipates a second serve. The intent is not to guess. It is to start the point with balance and depth.

What does that look like on tour? Against big servers he often starts neutral deep, then inches in once he has seen locations, using a compact block backhand to the middle third. Against medium pace serves he begins on the line and takes time away with a firm return to the opponent’s weaker wing. When servers start jamming the body, the trained forward hop frees his hands and keeps the swing short. The drill structure maps directly to those choices.

Serve efficiency, not just speed

When Sinner first appeared on the ATP Tour, his serve was more about starting the rally than finishing it. In Bordighera he spent heavy basket time on three targets on both deuce and ad courts: wide, body, and T. The job was not aces. It was immediate advantage. Two practical rules guided the work:

- First serve location charts must show variety. Ten balls out of ten to any single target is a fail because it becomes readable.

- Second serves must hit the outer half of a hand sized box above the net tape. The shape changes with the score, but the margin does not.

The result is what you now see in elite finals: a first ball that pushes returners into uncomfortable positions and a second serve heavy enough to stop them from attacking freely. Efficiency is the output. You notice short third ball forehands, cleaner service holds, and opponents missing more first serve returns than they expect.

Footwork, the skiing transfer

Late specialization can go wrong if the new sport fights the old movement. Here it fits. Alpine skiing taught hip shoulder separation, early weight transfer, and how to manage speed on uncertain footing. Piatti translated that into tennis with short step load and release drills. Example: a coach tosses two ankle high balls wide, then one high and deep. The player must keep the same upper body posture through all three. The aim is a stable head and a quiet hitting side while the feet work fast underneath. That is why Sinner slides into open stance backhands and still keeps the swing compact.

Scheduling choices that protect development

The academy did not chase every junior trophy. At 14 to 17, Sinner’s calendar favored extended training blocks and a limited set of tournaments that tested specific needs. There is a well known internal test from those years that reveals the logic. Piatti told him to navigate a local event independently, including trains and match logistics, and accept the result without the full team around. He lost in the Round of 16 and gained something more valuable: independence. The point for parents is not to engineer hardship. It is to set clear, age appropriate responsibility and let the athlete own the day.

Another often overlooked choice was surface exposure. In Bordighera he split time between clay and hard courts, but the technical targets never changed. Depth windows, height windows, and footwork tempo stayed constant. That choice reduced the typical dip when switching surfaces as a pro. If you are exploring an Italian base, study the daily rhythm at the Rome Tennis Academy training base and compare the structure.

The 2022 pivot: from academy to a pro team

After seven formative years with Piatti, Sinner made a clean professional decision in early 2022. He left the academy environment and built a touring team led by Simone Vagnozzi and Darren Cahill. The goal was not reinvention. It was refinement.

- Serve mechanics: they narrowed the toss window and stabilized his base, lifting first serve percentage without losing pace. It also improved the quality of his second serve under scoreboard pressure.

- Patterns at the top: against the best returners, they emphasized body serves to the backhand and quicker plus one plays to the forehand corner. Against the best baseliners, they added more down the line backhands earlier in rallies to break rhythm.

- Return variety: they kept the Piatti stations but added more aggressive starts on second serves, including the now familiar step in backhand block that lands deep through the middle to take away angles.

The continuity is the story. The Piatti base gave him a floor. The Vagnozzi and Cahill team polished the edges to win the biggest points.

The results that validate the choices

In 2024 Sinner rose to World No. 1, a milestone the ATP record of his No. 1 highlights. The on court fingerprints are clear: improved serve variety, aggressive but balanced returns, and lower error totals in rallies of five to nine shots.

You do not need spreadsheets to see the through line. The same down the line backhand that he repped in Bordighera appears at 4–all. The same three spot serve chart shows up when a final tightens. The same return stations underpin his ability to adjust return position within a set. The method scales.

What parents can learn, practically

Relocation at 13 is not for every family. Here is how to think it through.

-

Readiness checklist before moving

- Self management: Can your child handle schoolwork, laundry, and daily scheduling with light support? If not, build those habits at home first.

- Injury history: Frequent soft tissue issues suggest you need a slower ramp. Ask the academy to outline a gradual load plan.

- Motivation test: Have them train for a full week in similar volume locally. If they resent the work, a move will not fix it.

-

How to choose an academy fit

- Watch a regular Tuesday, not a showcase day. Are most reps live ball or only fed balls? Do players track targets or just hit?

- Ask for a 12 week plan with benchmarks for your child’s specific needs. Vague promises are a red flag.

- Meet the host or housing family if your child will not live with you. Agree in writing on curfews, school expectations, and who approves schedule changes. Sinner’s stable placement with a coach’s family and clear routines was as important as any drill, as Piatti recounts in Piatti on Sinner’s first years.

-

Plan the post academy transition from day one

- Define roles on a future touring team early: lead coach, performance coach, physio, and a single person in charge of the schedule. One voice must make final calls during tournaments.

- Build a simple data rhythm: track first serve percentage, unreturned serve rate, and return depth. Review them weekly. This keeps the group focused on controllables.

- Budget rehearsal: six months before leaving the academy, run a two week travel block with only the future team. Treat it like a dress rehearsal for life on tour.

For more models of how families and teams structure the pathway from academy to tour, see Djokovic’s Niki Pilic Academy years and Alcaraz’s JC Ferrero Academy path.

A coach’s menu you can copy this week

You do not need Bordighera weather to borrow the right pieces. Here is a compact menu any serious junior program can use.

- Backhand redirection block: 20 ball sets of two cross, one line, alternating deuce and ad courts. Score only the redirect. Goal is 70 percent in the line corridor.

- Return ladder: three stations for one set each. Deep, on the line, half step in. Five returns per station to a center target. Serve at 70 percent pace to emphasize placement.

- Serve variety circuit: three mini sets of 15 balls to each target. Record percentage in each box. Repeat until no single target falls below 65 percent accuracy.

- Modular fitness insert: between hitting sets, rotate 90 seconds of med ball rotational throws, 60 seconds of single leg stability, and 30 seconds of split step hops. The rule is pristine reps. Stop if technique fades.

- Autonomy rep: once a month, send the player to a local tournament with only a physio or a chaperone, not the full staff. The lesson is ownership.

The through line to the summit

Sinner’s story is not a romance about talent. It is a case study in sequencing. First a safe home base and clear routines. Then relentless, constrained repetition that built a swing for pressure. Then a carefully managed calendar that grew resilience without burning him out. Finally, a professional handoff to a touring team that refined patterns for the very top.

Each stage linked to the next. The host family solved the human side so the training could be hard. The training built a floor so the tactical tweaks could stick. The result is a player capable of carrying the number one ranking and winning under pressure across surfaces. That is the blueprint: stability first, then scale.

Closing thought

If you are a parent or coach deciding whether to move, pick the place that will make good habits feel ordinary. Demand clear drills, simple targets, and accountability that a teenager can actually live with. The best pathway is not glamorous. It is repeatable. Sinner’s climb from the Dolomites to World No. 1 shows that when the base is right, the peak is reachable.