From Dolomites to Bordighera: How Piatti Built No. 1 Sinner

The mountain kid who chose the sea

Jannik Sinner grew up where winter is a season of work. In Sexten, a village in the Italian Dolomites, the snow teaches balance, edge control, and calm breathing in cold air. He was a gifted ski racer, comfortable on steep slopes and in slalom gates. Then he made a decision that would define him: at 13 he left home for the Ligurian coast, moving to Bordighera to live and train at the Piatti Tennis Center. Years later, the boy who swapped skis for strings became world No. 1 and defended the 2025 Australian Open. The throughline is not hype or destiny. It is a system.

This is the story of that system. How an academy built a foundation without shortcuts, why he chose to leave it when he did, and what families can borrow from the journey. For parallels, see how Equelite built Alcaraz and IMG Academy shaped Korda.

The Piatti years: a base built to last

Riccardo Piatti’s center in Bordighera is known for turning talented juniors into durable pros. Sinner arrived as an unusually coordinated 13‑year‑old with a skier’s legs and a quiet mind. He did not bring the heaviest forehand on day one. He brought a willingness to repeat.

What did “fundamentals first” look like in practice?

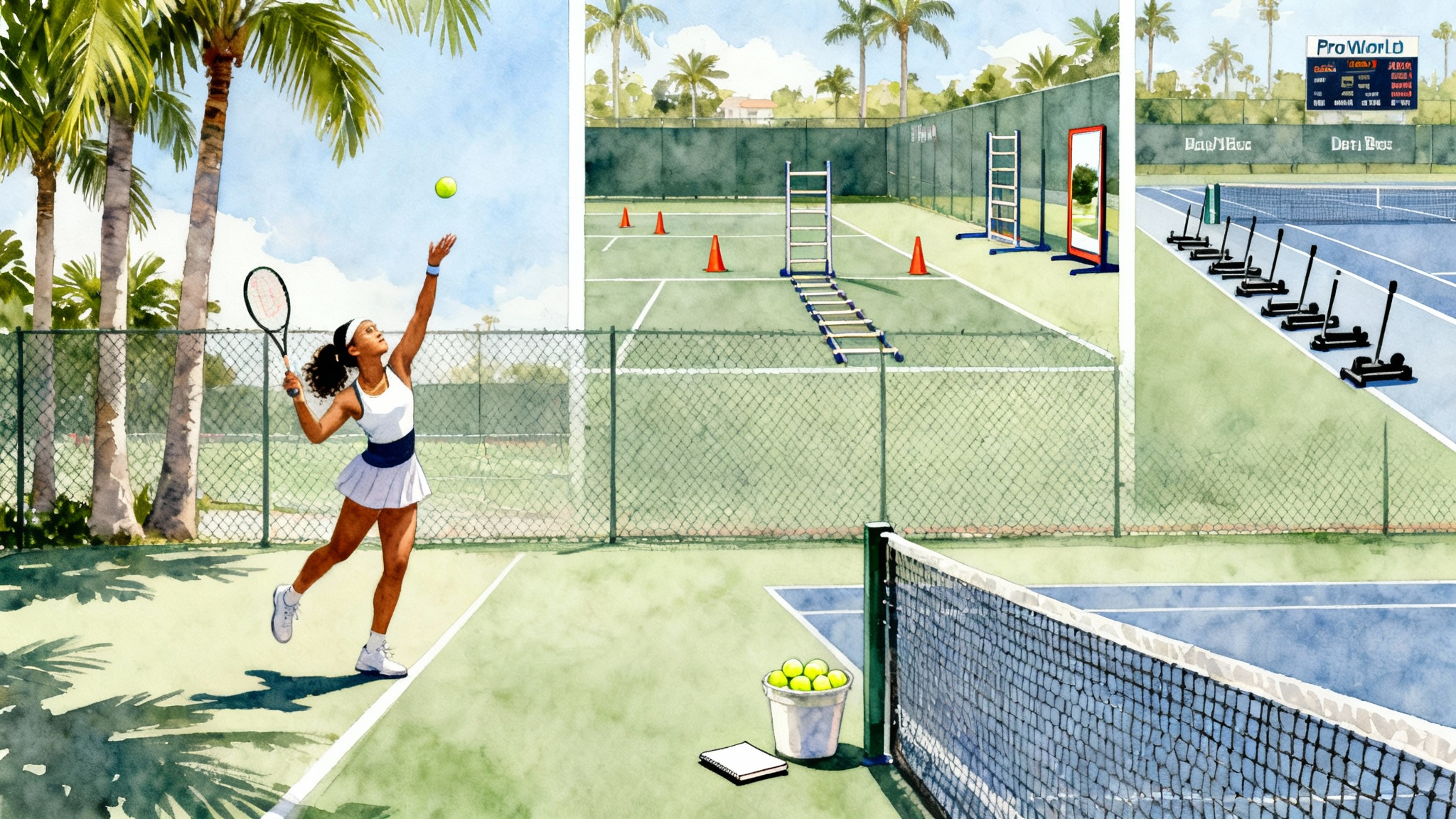

- Footwork before fireworks: Days opened with movement patterns without a ball, then with a ball, then under fatigue. Hop steps, split timing, first step to the line of the ball, recovery shape. Coaches would ask, “Where do your feet finish after a heavy crosscourt?” The answer mattered more than a one‑off winner.

- Clean stroke mechanics: Contact height, elbow path, and racket head speed were addressed through constraints rather than lectures. Cones for depth windows, foam targets for crosscourt lanes, and tempo cues like “three smooth swings” to synchronize upper and lower body.

- Clay‑volume reps: Much of the repetition happened on clay. Not because clay is romantic, but because it slows time a fraction, forces shape over slap, and multiplies decision reps per rally. That built a base for hard courts later.

- Targeted patterns: Sinner’s DNA became simple and repeatable. Examples: two heavy backhands crosscourt to pull the opponent wide, then a firm forehand to the open lane; or a backhand down‑the‑line change to freeze a right‑hander who is hedging. The patterns were trained until the choice felt automatic.

- Video as a quiet coach: Sessions were filmed often, then reviewed for one change at a time. A typical clip might focus on split‑step timing relative to opponent contact or the spine angle through the backhand.

The result was not instant headlines, but compound interest. By late teens, that base let Sinner hit big without wobbling. He learned to keep his torso quiet and get the racket up early, which makes his flat backhand skid even on slower courts. He learned to recover to the right place, so his offense did not leave him stranded.

Leaving at the right time: the 2022 pivot

In February 2022, Sinner made a hard call: he left Piatti to work with coach Simone Vagnozzi, later adding Darren Cahill. You do not walk away from a comfortable setup at 20 unless there is a clear reason. The reason was progression. The fundamentals were installed. What he needed were upgrades in match planning, serve patterns, return position, and between‑point pacing.

The Vagnozzi and Cahill team emphasized three changes that were visible within a season:

-

Serve clarity: Rather than chasing raw speed, they focused on locations first ball in, then disguise. Wide on the ad side into a forehand, body on the deuce to jam a two‑hander, and a better second‑serve kick to reclaim neutral.

-

Return aggression with permission to mix: Sinner began to start a step deeper against the biggest servers, trusting his first strike off both wings. On second serves, he moved in, took time, and aimed middle to cut angles.

-

Point tempo and recovery: He became deliberate with toweling and breathing between points. The goal was not to slow play, but to create a consistent reset that protected decision quality late in sets.

These were not cosmetic tweaks. They helped him win longer, tighter matches without redlining every rally.

Why the mountain skills mattered

Sinner’s skiing background did more than build quads. It taught eccentric control, hip‑to‑edge awareness, and an instinct for reading surfaces. On a tennis court, that becomes:

- Balance in open stance without collapsing the trail leg

- Comfortable deceleration into a slide on clay or a controlled hop on hard

- Head still at contact while the lower body handles the braking

Families often worry that a multi‑sport childhood will delay tennis development. Sinner is a counterexample. The agility and balance from skiing armed him to handle higher training loads while avoiding overuse breakdowns. Late specialization worked because the base was athletic, not just technical.

The proof: titles and a ranking that stuck

By mid‑2024, Sinner had taken the No. 1 ranking for the first time. The breakthrough Grand Slam came in Melbourne that January, followed by a season of consistent wins. In January 2025 he returned to Rod Laver Arena and, under pressure against elite opposition, played with the same unhurried balance he built in Bordighera, then refined with Vagnozzi and Cahill.

The timeline from mountain kid to No. 1 is often simplified into talent plus confidence. The fuller truth is more useful. It is a chain of well‑timed decisions: move away at 13 to build a base, stay long enough to automate fundamentals, then change teams when the next layer of skills required a fresh lens.

What families can steal from the blueprint

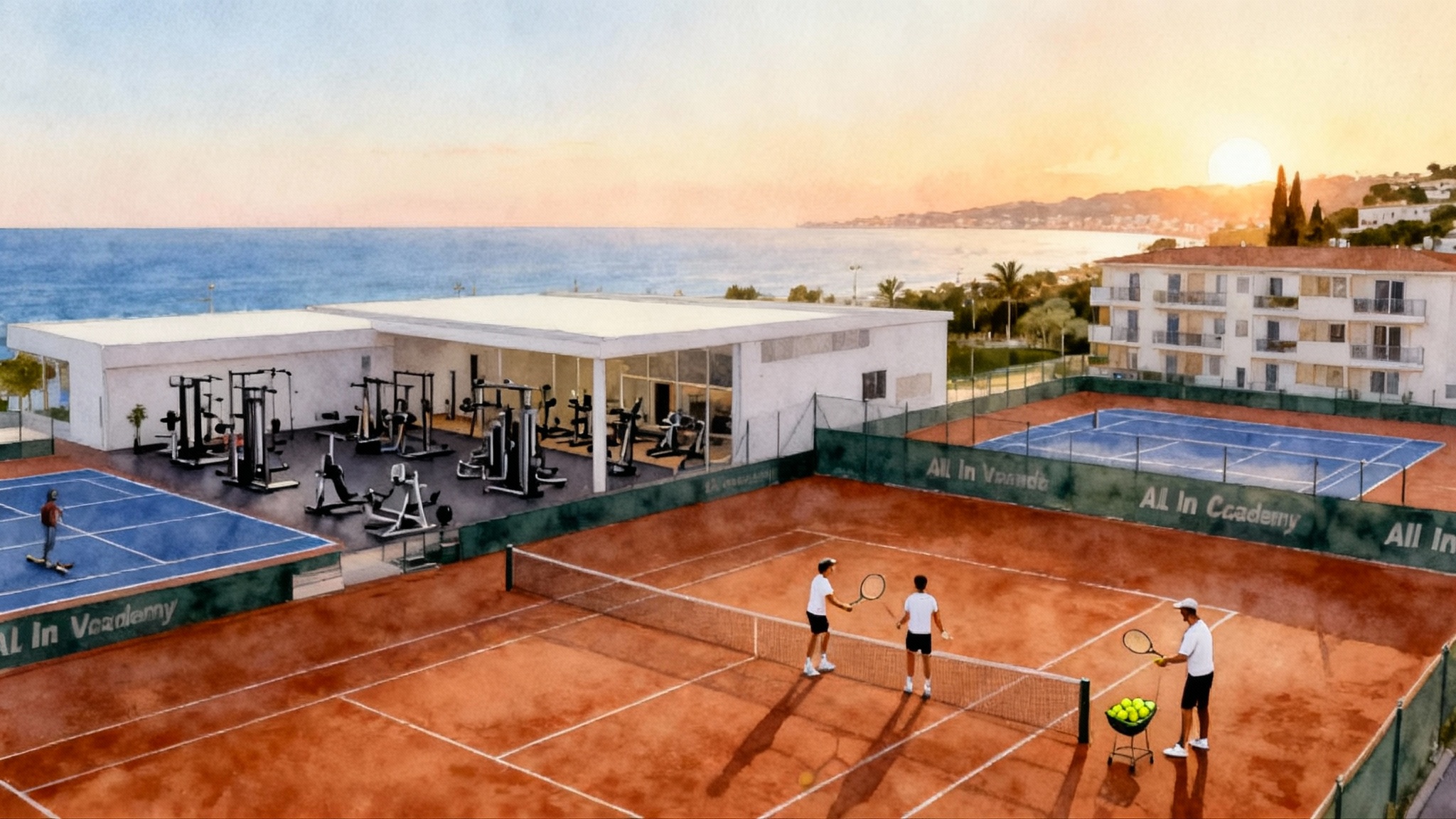

You do not need an academy on the Riviera to apply these ideas. Here are practical takeaways that parents and junior coaches can use this season. Players near the Riviera can also consider All In Academy on the Riviera.

1) Late specialization can work if the base is athletic

- Keep a second sport through age 12 to 13, ideally one that trains balance, hip control, and decision making under speed. Examples: skiing, basketball, or football. Two to three sessions a week are enough.

- Use a twelve‑week block where tennis footwork days alternate with the second sport. The test: vertical shin angle at plant, torso stability in change of direction, and landing mechanics. If those improve, serve speed and backhand stability will usually follow without chasing them directly.

2) Choose coach fit over brand

A big name does not guarantee progress. Fit does. Look for three signals in trial sessions:

- The coach starts with movement and spacing, not gimmicks

- Video is used to target one change per week, not five

- There are clear benchmarks for moving up a ball‑speed or intensity level

Ask the coach to define success in thirty days. If the answer is about a ranking rather than a measurable skill, keep looking.

3) Build a fundamentals block you can actually measure

Replicate the Piatti spirit at home with a six‑week block that emphasizes quality over novelty:

- Footwork ladder only if it is paired with ball perception. Better: the coach calls “short” or “deep” mid‑drill so the player must adjust steps.

- Depth windows: Use cones at one meter inside the baseline. Score rallies by balls that land past the cones with margin above the net.

- Pattern serving: Ten serves to each of three locations per side with a target for first‑serve percentage before moving on.

- Video twice per week from behind the baseline. Review for one habit: split timing, contact height, or recovery path. Keep the clip short and the cue shorter.

Metrics to track weekly:

- First‑serve percentage in target box

- Second‑serve points won in practice sets

- Rally ball depth past the cone line per rally

- Neutral‑to‑offense conversion rate by ball three

4) Periodize competition: Futures to Challengers to ATP

A simple four‑stage model helps juniors avoid jumping levels too soon.

- Stage A: Train‑heavy, local tournaments. Gate to advance: hold 70 percent of service games and break 35 percent over a four‑tournament sample.

- Stage B: National events and select ITF junior starts. Gate: three finals at that level in six months or a rolling Elo that reflects top 15 percent in region.

- Stage C: Entry‑level pro events. Gate: two quarterfinals and one semi in Futures within twelve events, with hold‑plus‑break percentage above 105 combined.

- Stage D: Challengers. Gate: two quarterfinals and one final within eight events, with average return games won above 25 percent against top 200 opponents.

Hold your athlete to the gate. Moving up early might feel exciting. Moving up when the numbers say ready compounds confidence and rating.

5) Use video like a scalpel, not a floodlight

- Limit reviews to ten minutes, twice a week, with one key point and one slow‑motion clip

- Pair each point with a single constraint in the next practice. Example: if split timing is late, start one step higher and use a metronome clap on opponent contact for three drills

- Archive “before and after” clips to make progress visible. Motivation follows evidence.

6) Borrow the Bordighera patterns

You can practice the same ideas without elite ball speed. Try these simple, repeatable patterns:

- Two backhands crosscourt to push the opponent wide, recover to center minus one step, then change line with depth

- Serve wide on the deuce court, first ball to the open ad corner, then backhand redirect if the opponent floats short

- Second‑serve return middle and heavy, step in on ball two, look middle again to deny angles

The goal is not a perfect winner. The goal is a predictable first advantage after ball three.

The move at 13: what it really took

Sinner’s choice to leave home so young is often framed as fearlessness. He has described it more simply. It was a risk worth taking, made manageable by structure. He lived with a coach’s family, learned Italian properly, and created a routine that made lonely days survivable. The French Open’s official site has documented how he moved to Piatti at 13 and settled into a new life in Bordighera.

Families considering a similar move can pre‑solve the three problems that derail many relocations:

- Housing with adults who understand athlete schedules

- A weekly check‑in with parents on sleep and school, not just results

- A local mentor who is not the head coach and can translate emotions during rough patches

The decision to leave: why it unlocked the next level

By early 2022, the core was built. Staying would have been comfortable, but comfort does not often produce a first Grand Slam title. Changing to Vagnozzi and adding Cahill shifted the focus from building tools to using them against the very best. Serve patterns matured. Return depth went up. Between‑point management improved. The result was not just one big week. It was a stable top level that held in finals and five‑setters, then a second Australian Open the following January.

If you are a parent, the lesson is portable: do not chase novelty for its own sake, but do not cling to habit once the goal has changed. Foundations are for building on, not for living in forever.

A checklist for the next six months

For families and coaches who want a simple plan, here is a six‑month checklist inspired by Sinner’s path:

- Month 1: Assess movement. Film from behind for split timing and recovery path. Install a two‑word cue, such as “land early” or “hips first.”

- Month 2: Add pattern serving. Three locations each side, with first‑serve percentage goals and second‑serve point targets in practice sets.

- Month 3: Depth discipline. Cones one meter inside baseline. Count only balls that clear the net by a racket and land past the cones.

- Month 4: Competition gate. Enter events only when combined hold plus break is above 100 across practice sets. Stay one level down until this sticks for three consecutive weeks.

- Month 5: Return shape. Start deeper against first serves and step in on seconds. Track middle‑return percentage and second‑serve return points won.

- Month 6: Review and reset. Compare clips from Month 1 to Month 6. Choose one new cue and one new constraint. Repeat the cycle.

The bigger picture

From the Dolomites to Bordighera to Melbourne, Sinner’s rise is not a fairy tale. It is a sequence of specific choices that added up. A fundamentals‑heavy childhood at Piatti’s center created a calm, heavy hitter who did not need to redline to win. The 2022 change to Vagnozzi and Cahill added the tour‑grade layers: serve plans, return positioning, and match management. By 2025, those layers held under the brightest lights in Australia. The mechanism is clear, and so are the implications for developing players.

Families can respect the calendar of growth. Keep the second sport long enough to build a real body. Choose coaches who teach footwork and spacing before branding. Use video to change one thing at a time. Advance competition levels only when the numbers say ready. If you do, your player may not become world No. 1, but they will become the kind of athlete who can keep improving without breaking.

In the end, Sinner’s path shows that excellence is quieter than it looks on television. It is a teenager repeating crosscourts on clay until his feet know the answer, then an adult choosing a new team when the next question appears. That is how you go from a mountain village to the top of the sport and stay there long enough for the view to feel like home.