From Murcia to Villena: How JC Ferrero’s Equelite Built Alcaraz

Carlos Alcaraz’s rise did not happen by accident. It was a series of precise choices: signing early with agent Albert Molina, relocating at 15 to live and train full time at JC Ferrero’s Equelite, and moving step by step from ITF to Challengers to ATP.

The road that actually built a champion

Every great tennis story starts with a place. For Carlos Alcaraz, it began in El Palmar, Murcia, and crystallized 75 miles away in Villena, at Juan Carlos Ferrero’s Equelite Academy. The move was not cosmetic. In September 2018, at 15, Alcaraz left home to live where he trained. That single decision turned potential into a plan: a campus where his coach, fitness, physio, courts, and school rhythm sat inside one ecosystem. That compounding approach echoes what we saw in Piatti Academy and Sinner.

Before that relocation, another critical piece clicked into place. Spanish agent Albert Molina had tracked Alcaraz since he was a skinny 11‑year‑old on the Nike junior circuit. Molina signed him at 12, convinced the family he could build the right support, and helped steer him toward Ferrero and Villena. It was a bet on infrastructure and people rather than hype, and it set a professional standard early in his journey. See the Alcaraz early team story.

Why Equelite, and why full-time living matters

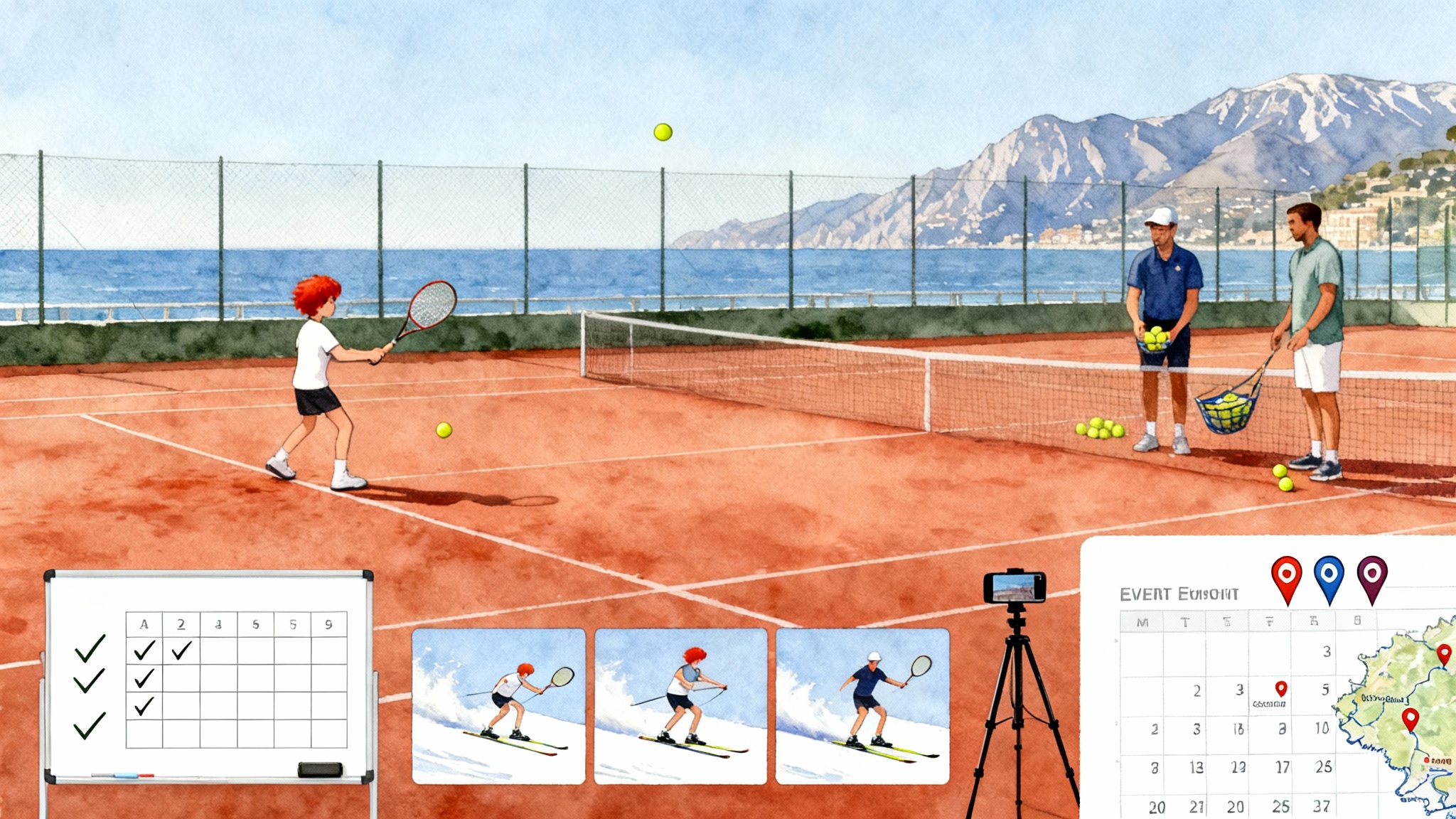

Most academies promise courts and coaches. Fewer deliver a daily life that eliminates friction. At Equelite, coaches and staff live on site. That changes everything. Breakfast, hitting slots, schoolwork, lifts to the gym, treatment, lights out. The system leaves little room for drift, which is often the real opponent for a 15‑year‑old who suddenly trains like a pro. This integrated boarding model is similar to the All In Academy model.

The campus matters because it compresses feedback loops. If a coach adjusts the forehand takeback at 10:00 a.m., the fitness coach can tweak medicine‑ball patterns at noon, and the physio can unload a nagging wrist at 4:00 p.m. The next morning, the change is reinforced on court. That speed of iteration is how technique becomes identity.

Facilities support that pace. Equelite is a year‑round site with clay, hard, indoor, and even a grass strip, plus a gym, track, and in‑house physio. Variety lets coaches control the environment. When the staff wants more skid and lower contact points, they set a hard‑court week. When they want more traction and patience, they book clay blocks. The player does not chase conditions; the staff programs them.

One voice, consistent message

Alcaraz’s core advantage was not a secret weapon. It was continuity. Juan Carlos Ferrero, a former world number 1 and Roland Garros champion, became the primary coach when Alcaraz arrived in Villena. That continuity is deceptively powerful. Teenagers often collect tips. Pros build a language. With one technical dictionary, every adjustment connects to a larger picture: neutral ball height, contact point discipline, serve patterns by score, on‑ball and off‑ball decisions at the net.

Ferrero’s influence shows in the balance of aggression and percentage. Watch Alcaraz’s forehand patterns: heavy through the middle early in rallies to compress angles, then a sudden short‑angle forehand or drop shot when the opponent’s base narrows. That is not improvisation. It is rehearsed shape recognition.

Building the body for an all‑court game

The Equelite plan treated physicality as a skill, not an afterthought. The staff periodized around developmental goals more than the calendar. Early blocks emphasized movement economy, especially first step and deceleration mechanics. Later blocks piled in repeated accelerations, change of direction, and shoulder‑care microcycles to support higher serve speeds without sacrificing touch.

Physio was present, not occasional. Teen bodies grow in uneven bursts. Having treatment rooms next to the courts meant issues were caught at soreness, not at injury. A tight hip after a heavy clay session could be cleared and re‑tested that same day. Over a season, those small saves keep growth on track.

The competition ladder: ITF to Challengers to ATP

The tournament pathway was as deliberate as the training. The team did not jump levels for visibility. They climbed for readiness. First came professional points at International Tennis Federation events to experience the week‑to‑week grind. Then, when match stamina and patterns held, they leaned into Challengers.

In February 2020, at 16, Alcaraz earned his first ATP main‑draw win in Rio after a midnight finish, outlasting Albert Ramos Viñolas in three sets. The result proved the training could travel to the tour stage. Later that summer, at 17, he collected a first Challenger title in Trieste, then added Barcelona and Alicante to close the year. That stretch delivered ranking traction and confirmation that the plan scaled under pressure. See Alcaraz first Challenger title.

The milestones after that came fast: first ATP title in Umag 2021, deep runs against top players, and a major title as a teen. It looked like a surge. In reality, it was compounding. Each rung prepared the next.

Targeted scheduling and smart rest

Scheduling was a chessboard, not a calendar. The team built tournament clusters that echoed training themes:

- Surface blocks matched competition runs. Clay training bled into clay events, then a reset block preceded hard courts. This preserved technical feels and reduced the cost of surface change.

- Geographic clustering reduced travel fatigue. Spain and nearby European stops dominated early steps, with occasional targeted wild cards where the learning payoff was high.

- Rest windows were protected. After scoring a big result, the instinct is to keep swinging. The team often did the opposite, inserting a short training block to consolidate gains and rebuild legs. That is how the body absorbs jumps without breaking.

The style, explained simply

Alcaraz’s game looks freewheeling. Underneath is a template that Equelite drilled across surfaces. For more on multi‑surface development, see the Rafa Nadal Academy blueprint.

- Serve and first strike: High‑percentage first serves that open space, followed by a forehand inside the baseline. On days when the serve misfires, the plan shifts to body serves to force short middle returns, a safer launchpad for offense.

- Two‑speed baseline: Heavy forehands to the center third to stretch depth patterns, then a quick change of pace with short angles or a disguised drop shot once the opponent’s court position creeps back.

- Early net choices: Closing behind the short‑angle forehand is not flair. It is math. A forced low pass, plus fast feet and soft hands, turn neutral points into plus‑one opportunities.

Why did this develop so fully so young? Because the academy practiced the same ideas on different surfaces. Clay days tested patience and height. Hard days tested timing and court positioning. The identity stayed constant while the demands changed, which made the toolkit travel anywhere.

What families can copy from the Equelite model

You do not need a grand slam budget to borrow this blueprint. You need clarity and consistency.

- Choose a coach for alignment, not just a name

- What to do: Interview coaches about their teaching language, match coaching habits, and how they collaborate with fitness and physio.

- Why: Teenagers need one clear voice more than a collection of opinions.

- How: Ask for a written development plan with checkpoints every eight to twelve weeks.

- Live where you train, at least in blocks

- What to do: Even if full relocation is impossible, schedule four to eight week on‑site blocks where the player stays at or near the academy.

- Why: Daily rhythm and fast feedback are worth more than occasional high‑intensity days.

- How: Use school breaks or off‑peak windows to create mini‑residencies.

- Build year‑round multi‑surface habits

- What to do: Rotate clay and hard weekly, and add indoor sessions to practice lower contact points.

- Why: Variety builds a game that adapts, which pays off in qualifying rounds and early‑career travel.

- How: Plan two or three surface blocks per quarter, with clear themes and drills.

- Treat fitness and physio as part of coaching, not add‑ons

- What to do: Budget time for prehab and recovery after every heavy session.

- Why: The fastest way to stall a rising player is a preventable injury.

- How: Track training loads simply. A paper log with session rating of perceived exertion and minutes is enough to spot trends.

- Climb the ladder deliberately

- What to do: Step from ITF to Challengers only when training themes hold under match stress for several events, not one hot week.

- Why: Ranking shortcuts are expensive if the underlying game is not ready.

- How: After each swing, review three metrics: break points created per match, first‑serve points won, and net points won. If two of three move in the right direction across the swing, you are ready for a higher tier.

- Schedule around development, not just points

- What to do: Cluster tournaments by surface and region, then plant short training windows after peaks.

- Why: Gains stick when you consolidate them.

- How: Build a quarter as a sequence: train block, three‑event swing, micro‑reset, second swing.

- Keep the circle small and specialized

- What to do: Define roles. Who is primary coach, who runs fitness, who covers physio, who manages logistics.

- Why: Clarity substitutes for size. A small, aligned staff beats a large, scattered one.

- How: Make a one‑page org chart with names, weekly touchpoints, and decision rights.

How to evaluate an academy against this standard

Use a checklist when you visit, whether in Spain or close to home.

- Integration: Are fitness, physio, and tennis planned together, or do you book them separately with different goals?

- Surfaces: Can your player train on at least two surfaces every week? Ask to see the schedule, not just a brochure.

- Coach access: Does the primary coach attend fitness reviews and post‑match debriefs, or do departments operate in silos?

- Feedback cadence: How often do players receive written notes or video clips? Weekly touchpoints beat sporadic “how do you feel” chats.

- Tournament planning: Will the academy help map an ITF to Challenger pathway with dates, not wish lists?

- Housing and school: Can the player live on site or nearby during intensive blocks, and is there academic support appropriate for their age?

- Data without overload: Do they track a handful of metrics that matter for your player’s style, or drown you in dashboards with no decisions attached?

The real spine of Alcaraz’s rise

Look past the winners and you see systems. An early, trusted agent opened doors and guarded decisions. A move to Villena put a teenager inside an adult framework that accelerated learning. One coach voice kept the message coherent. On‑site fitness and physio made adaptation safer and faster. Targeted scheduling made progress predictable, not streaky. The result looks like talent flowering. It is also the product of many very specific choices made early and applied daily.

Families often ask for a single secret. Here it is: design beats adrenaline. If you can assemble a small, aligned team; live where you train in meaningful blocks; build multi‑surface fluency; and climb the calendar with intention, you do not guarantee a champion. You do something more practical. You give a young player the best possible chance for their ceiling to show up when it matters.

From Murcia to Villena, that is the lesson.