Belgrade to Munich: How Pilic’s Academy Forged Novak Djokovic

A timely tribute and analysis of Novak Djokovic’s formative years at Niki Pilic’s academy in Munich. We unpack the family’s relocation, the discipline-first culture, older sparring partners, and how these shaped his return game and resilience. Practical takeaways for parents included.

Why this story matters now

The tennis world has long credited Niki Pilic with shaping champions. Among them, Novak Djokovic stands apart, and not only because of his titles. His game looks engineered for pressure. The return lands deep, the mind does not blink, and the body repeats precise patterns long after opponents fade. That did not happen by accident. A big piece of the blueprint was drawn in Oberschleissheim, a suburb north of Munich, at Pilic’s academy. At age 12, Djokovic left Belgrade for that small base in Bavaria, a move that rerouted a family and quietly set a standard for how a serious junior can grow into a professional. The decision, the daily discipline, and the people around him formed a whole. If you are a parent weighing academy options, or a coach defining training blocks for a teenager with ambition, this story offers a practical map.

The decision: leaving Belgrade at 12

Every breakthrough begins with a choice. For the Djokovics in 1999, the choice was to send their eldest son away from home so he could practice in an environment that offered consistent courts, experienced coaches, and a peer group that would stretch him. The move was not glamorous. It was a gamble with real costs. Djokovic’s parents ran a modest family business and took on debt to support his development. He attended Niki Pilic’s academy in Munich at age 12, a fact recorded in the ATP Tour player bio, which notes extended training there before resettling to compete from Serbia. That early relocation put him in a structured, high‑repetition system that aligned with his personality and goals at exactly the age when habits harden.

Parents often ask whether 12 is too young to leave home. The better question is whether the training environment at that age is coherent. In Djokovic’s case, Belgrade gave him an exceptional foundation with Jelena Gencic, who emphasized technique, attention, and love for the craft. Munich then gave him order and scale. The two systems complemented each other. One taught him to listen to the ball. The other taught him to outlast it.

Inside the Pilic method: discipline first, always

What did days at Oberschleissheim actually look like? They were built on measurable work. Former coaches at the academy have described a program that demanded hours on court and additional physical work, sometimes rounded out with running around the adjacent Olympic rowing basin, a landmark from the 1972 Summer Games. Reports from the time describe four hours of tennis and another hour of strength work as a normal day for the young Djokovic, as recalled in a France 24 academy profile. For footwork context, compare this to our timing focus in the split-step mastery guide.

Discipline at Pilic’s academy did not mean disguising the grind as fun. It meant knowing exactly how much volume a player completed, how cleanly, and under what level of fatigue. Djokovic loved that clarity. He could trace his progress across simple baselines. Did he hit his targets in a 20 minute crosscourt rally without an unforced error. Did he meet the time standard on a run around the basin. Could he serve to the same corner 30 times and land at least 25. The staff reframed talent as repeatable output.

Structured training blocks: how repetition became a weapon

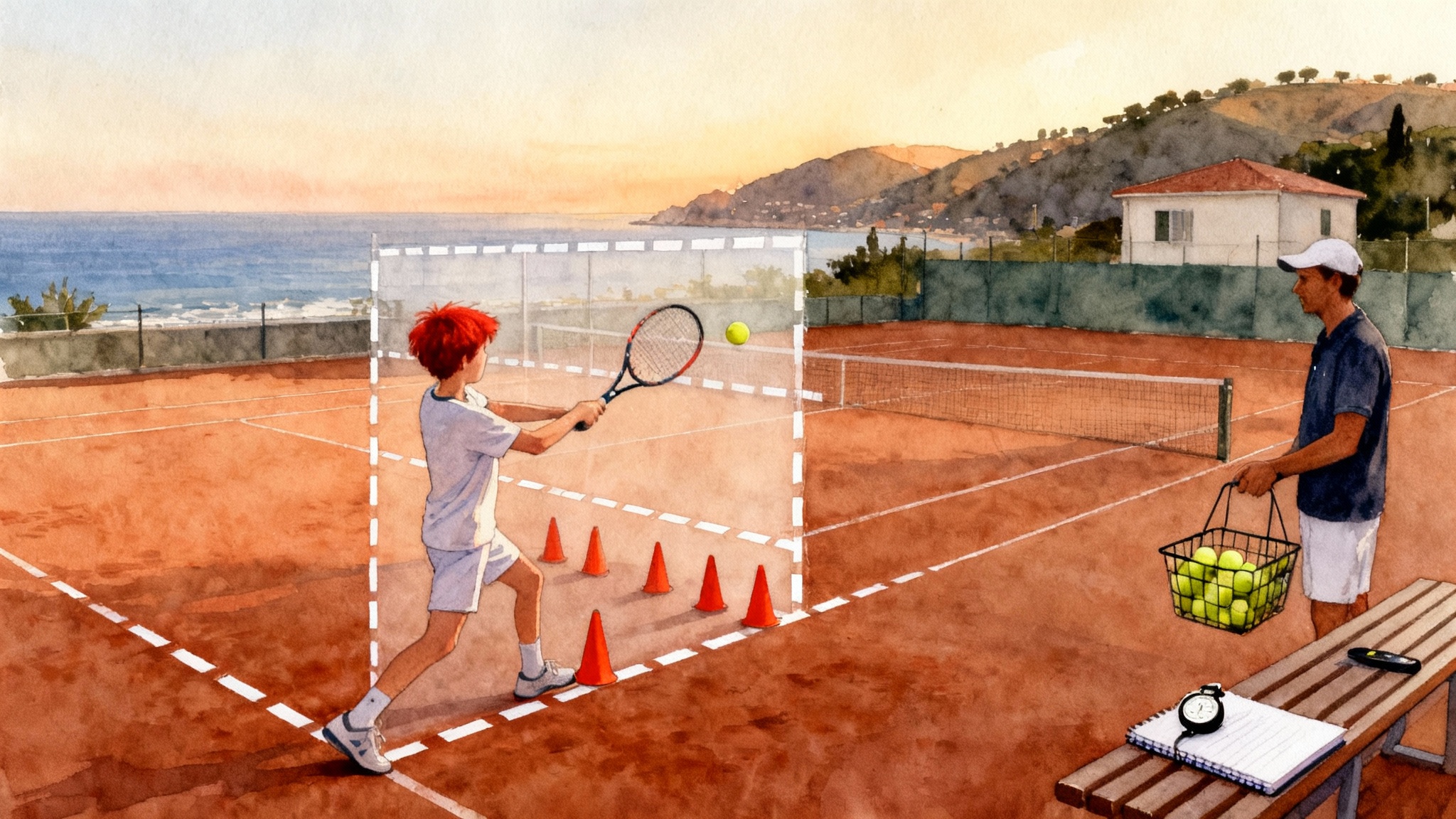

Training at Pilic’s academy came in blocks that were simple to describe and hard to execute. The template looked like this.

- Technical block: one to two hours of stroke work with a narrow focus, often just two patterns per day. Example: backhand crosscourt depth to the last meter of the baseline, then backhand down the line off a feed, alternating every third ball. The goal was not variety. The goal was quality at repetition.

- Live‑ball block: one to two hours of situational play, such as first‑ball attack off a second serve, return plus one, or neutral rally under a depth constraint. If a ball landed short, the point restarted. This built compliance to depth and trained patience without passivity.

- Physical block: about an hour on strength and movement. Emphasis was on elastic power, footwork patterns, and durability. Think medicine ball throws for rotational sequence, skipping variations for rhythm, and acceleration runs that mirrored the burst of a return.

Over time, this block structure bakes into a player’s identity. The repetition is not a punishment. It is patterning that allows the brain to default to reliable solutions when the match tightens. You can see it later in Djokovic’s career in how often he wins neutral rallies from slightly behind position. That is the echo of thousands of depth‑constrained reps. For a modern contrast, see the load management in Sinner’s Piatti Academy path.

Older sparring partners: the useful discomfort

Pilic’s academy had a healthy ladder. A motivated 12 year old might hit with a 15 or 17 year old who served heavier and took the ball earlier. Sometimes a young pro or high level college player passing through Munich would jump into practice sets. That gap created useful discomfort. When you are the youngest on court, you learn to neutralize pace and absorb pressure. You also learn to organize points without brute force.

Two adjustments showed up early in Djokovic’s practice sessions in Munich.

- Contact point discipline: against older hitters, you do not get clean looks. Djokovic standardized his contact point higher on the backhand and slightly more in front on the forehand so he could redirect pace without over‑swinging. That conserved energy and prevented short balls.

- First step urgency: the first two steps into the split step and out of it became non‑negotiable. Playing older opponents forced him to make micro‑decisions earlier. That timing is why his returns often look early rather than rushed.

If you coach a junior, mix in practices with slightly older or stronger players twice a week. Do not overdo it. The ratio can be one practice at level, one slightly above, and one where your player is the hammer so confidence and pattern ownership stay intact.

The return game, built brick by brick

Djokovic is widely viewed as one of the sport’s greatest returners. Think of how his returns change the geometry of a point. The serve buys many players a free ball. Against Djokovic it often buys a neutral ball at best. That skill traces to specific habits embedded during his Munich years.

- Deep middle as the default: many juniors are taught to go aggressive to the corners on return. Pilic’s structure often favored a different priority on the bulk of reps. Land the return deep through the middle third, take time from the server, and invite the next ball to sit up. Once the returner owns neutral, the rally unfolds on his terms. Djokovic reheated that pattern thousands of times.

- Keep the strings on the ball: when facing pace from older servers, he learned to shorten the backswings and trust the strings rather than his arm speed. That cue prevents the common junior error of slapping long under pressure.

- Serve‑read library: repeated exposure to stronger servers built a mental catalog of toss tendencies and preferred patterns. He did not guess. He recognized and reacted.

A simple return session you can steal: 150 first serves received, grouped as 15 sets of 10. The target is deep middle on 8 of 10 in each set, with video feedback for height over the net and bounce location. Rest between sets is exactly 60 seconds to simulate the rhythm of games. Track make percentage and average depth. Repeat twice a week for six weeks and re‑test under match conditions.

Mental resilience as a daily skill

Talent gets you to the door. Resilience gets you through it. Living away from home teaches logistical independence. Training with older players teaches humility. Doing it on a budget teaches focus. At Pilic’s academy, resilience was not a speech. It was a sequence of small tasks that had to be done exactly right.

- Load under constraint: the coaching staff often paired skill with fatigue, then held the technical standard. For example, return plus one patterns late in the session, with the rule that a short ball restarts the point. This trains clarity when legs are heavy.

- Quiet repetitions: there was no orchestra of sensors or flashy tools. The wall, the lines, the clock, and a coach were enough. Djokovic often rehearsed alone, bouncing the ball against a wall until he hit a certain depth target. That is how patience gets wired.

- Social support: the academy setting creates an extended family. Mentors matter. Standards first, then calm.

If you are scouting in Germany today, an option for compact, high‑intensity work outside Bavaria is the Alexander Waske Tennis‑University.

Balancing costs with schooling: the family calculus

The decision to send a child to an academy abroad is not only about tennis. It is a financial and educational choice. The Djokovic family juggled travel, tuition, equipment, and living expenses and still found ways to keep Novak’s schooling on track. Parents considering a similar path can borrow a few principles.

- Price the full year: include tuition, living, tournament travel, stringing, and conditioning support. Add a 15 percent buffer for the unexpected.

- Ask for modular support: some academies offer partial‑week training or seasonal blocks. Use those to match your budget to peak development windows. The aim is not to be there forever. It is to get the right dose at the right time.

- Choose a school pathway that is portable: look for academies with integrated schooling or recognized online programs that transfer credits cleanly. Confirm how many tournament weeks the school will tolerate and what make‑up work looks like. Get it in writing.

- Build a sponsor file early: local businesses, regional federations, and community groups often support promising juniors. Assemble a simple one page profile with results, goals, and budget. Treat sponsorship like a partnership and send updates.

How to evaluate academy fit like a pro scout

When families visit academies, tours can blur together. Use a checklist that forces specifics.

- Culture on court: watch two full sessions. Are footwork, depth, and first step timing coached, or only hit harder messages. You want clear, repeatable cues and patient coaching.

- Coach to player ratio: technical blocks should be intimate. One coach feeding four players is acceptable for live ball. True stroke changes need smaller groups or individual time.

- Peer ladder: ask who your child will train with most often. You want a spread that includes equal peers and slightly stronger hitters who can push without crushing confidence.

- Measured work: how does the academy track reps, errors, depth, and speed. Video is helpful, but even a simple depth chart and error log shows seriousness.

- Tournament calendar: does the staff help with entries, travel groups, and post match debriefs. Growth happens in events as much as on courts.

- School fit: walk through the school day and meet the education lead. Review past examples of students who balanced heavy travel.

For additional comparisons of academy structures and outcomes, see our case studies on Sinner’s Piatti Academy path and the split-step mastery guide.

A four week block you can borrow

Inspired by the structure reported from Oberschleissheim, here is a simple four week template that blends volume with recovery. Adjust the total minutes to your player’s age.

- Week 1 load: three days of two session tennis, one strength session, one mobility session, one match play day, one full rest day. Total on court time about 16 hours.

- Week 2 load: mirror Week 1, but swap one live ball block for targeted return work and add one conditioning run with gentle intervals.

- Week 3 test: keep volume steady, add match play under constraints. Example: start every game at 30 all to weight pressure points. Track break points created and saved.

- Week 4 absorb: reduce tennis volume by 25 percent, keep strength and mobility, and emphasize technique touch ups and video review.

Daily schedule sample for a school day in the load weeks.

- Morning: 75 minute technical block focused on one pattern only. Short video check at the end.

- Midday: school work and recovery meal. No phone during meals to keep focus and digestion calm.

- Late afternoon: 90 minute live ball block, with 20 minutes dedicated to return patterns and 20 minutes to serve targets. Finish with 15 minutes of mobility and breath work.

The template honors a simple truth. Players do not become consistent by hoping. They become consistent by stacking consistent days.

What carried into Djokovic’s pro success

- Pattern patience: in big matches, Djokovic rarely panics. He prefers to reclaim neutral and force a second decision from the opponent. That rhythm traces to depth rules and live ball constraints from his academy days.

- Decision speed on return: the early read, the compact swing, and the deep middle default all come from repetition under pressure. When the rally starts even after your return, you win a long match.

- Body as metronome: four hours on court and an extra hour of strength, repeated over years, built a base that lets him maintain form late in tournaments. Fitness is not a side project. It is the frame that holds the art.

- Love of work: the best academies take the drama out of hard days. Pilic’s culture did that. Djokovic learned that effort is not news. It is normal.

Practical takeaways for parents

Here is the short list to take to your next academy visit or planning meeting.

- Fit beats fame: choose the place that matches your child’s temperament and learning style over the one with the most famous name. Watch how coaches speak to players under fatigue.

- Verify structure: ask to see a standard weekly plan, the ratio of technical to live ball work, and how return training is integrated. You want explicit blocks, not vague promises.

- Prioritize peer quality: your child will be molded by the four or five players he or she trains with most. Meet them. Watch a set.

- Demand measurement: consistent progress requires consistent measurement. Ask how the academy logs depth, errors, fitness standards, and match stats.

- Plan the money and the school: price the full year, pick a portable school option, and create a sponsor file. Do not let stress from logistics bleed into performance on court.

- Keep a home base: even if you go abroad for blocks, maintain a local coach who knows the long arc of your child’s development. Continuity avoids random reinventions.

Final word

From Belgrade to Munich, Novak Djokovic’s path through Niki Pilic’s academy shows how a teenager becomes a champion the slow way. A family chooses structure over comfort. An academy trades flash for measured work. A child learns to aim deep middle on a return and to breathe when legs burn. The result is a game built to last. If you are a parent or coach, borrow the principles that made that transformation possible. Choose fit, build blocks, measure the work, and protect school and budget with the same seriousness you protect technique. Do that, and your junior will not just get better. He or she will learn how to stay better under pressure, which is the real difference between a promising player and a professional who endures.