From Wuhan to Barcelona: Beijing and GR Tennis Built Zheng Qinwen

Zheng Qinwen’s rise was not accidental. It ran through two academies that shaped different parts of her game: Carlos Rodríguez’s Beijing base and GR Tennis Barcelona under Pere Riba. Here is how those choices led to an Australian Open final, Olympic gold, and a top‑5 ranking, plus what families can copy.

The two-academy map behind a modern champion

Trace Zheng Qinwen’s career on a map and you see a clear pattern: each move solved a specific problem at a specific age. She left her hometown of Shiyan for Wuhan at eight to find daily competition. Three years later she went to Beijing for structure and foundational technique at Carlos Rodríguez’s academy inside the Potter’s Wheel International Tennis Center. In 2019 she relocated with her mother to Barcelona to absorb Spanish clay volume and tactical schooling at GR Tennis Barcelona, the program co-founded by Pere Riba and Marcel Granollers. In late 2023 she reunited with Riba, and twelve months later she had the results to prove the plan worked: Australian Open finalist, Paris 2024 Olympic singles gold, and a top 5 place in 2025. When a path is this intentional, families can borrow the logic even if the budget, passport, or language are different.

To ground the big claims: Zheng reached the 2024 Australian Open final, then, at the Paris Games played at Roland-Garros, she defeated Donna Vekic for Olympic gold. Her ranking entered the top five during 2025. Those are outcomes. The more useful story is how two training cultures forged the habits that produced them.

Beijing: technique, discipline, and a professional daily rhythm

Carlos Rodríguez is famous for coaching Justine Henin, then Li Na. His Beijing program exported the same clear standards to a Chinese base: repeatable swings, compact preparation, and a day built around punctuality, video, and habits. For a pre-teen Zheng, that meant learning to load through the hips rather than muscling the ball with the arm, finishing forehands with balance, and using footwork ladders until correct spacing felt automatic. The environment was consistent and predictable for a young player living far from home. Uniforms were tidy. Warm-ups started on time. Stretching was not optional. The message was simple: what you do every day beats what you do once.

Think of this stage as pouring concrete. If the foundation is level, you can add floors later without cracks. In practical terms, the Beijing block solved three early-career problems that hold juniors back:

- Technical drift under pressure: the staff corrected little breakdowns before they hardened into a style. The forehand take-back stayed compact, the toss height matched the serve rhythm, and the two-handed backhand loaded the outside leg first.

- Fitness baselines: weekly testing and steady aerobic work built an engine. Sprint ladders were not punishment; they were part of the craft.

- Daily professionalism: film review and written checkpoints turned feelings into notes. Juniors who can articulate why they missed a return can fix it faster.

The result was a player with clean shapes and reliable mechanics. But clean mechanics alone do not win on tour. You need to solve matches, not just strokes. That is where Barcelona comes in.

Barcelona: clay volume, pattern literacy, and game management

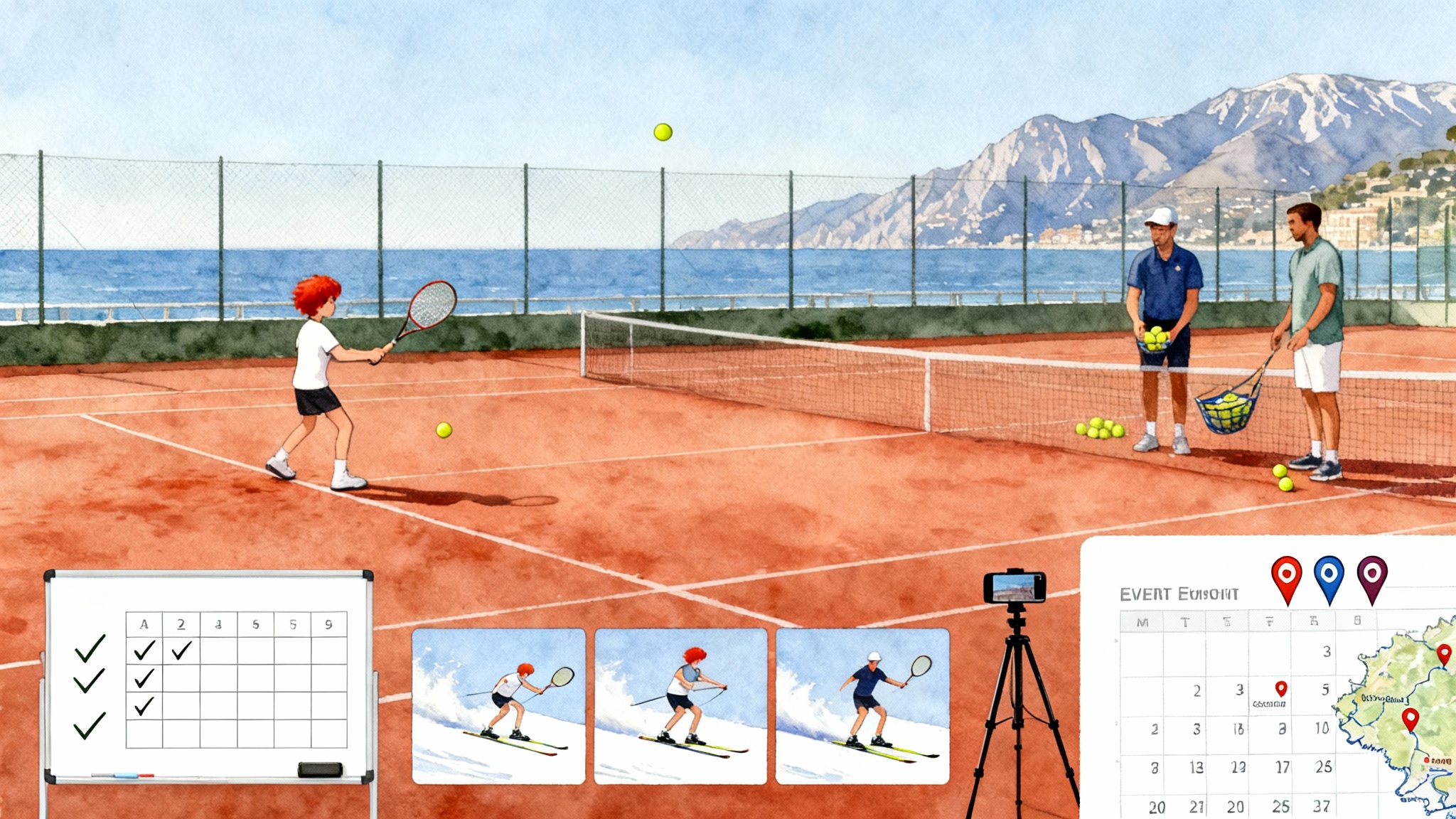

In 2019, Zheng and her mother moved to Barcelona to train at GR Tennis Barcelona under Pere Riba. Spain does not only offer red clay. It offers the culture that comes with it: longer sessions, longer rallies, and coaches who speak in patterns more than in tips. The first months looked like this: heavy clay volume to hardwire patience, dozens of crosscourt-plus-inside-in combinations, and side-to-side defense that ends in attack, not in neutral. She also adjusted to the Spanish rhythm of work, where doubles points, hand-fed drills, and live points cycle in a loop until decision-making looks natural rather than rehearsed.

If Beijing poured the concrete, Barcelona taught her to drive the car in traffic. Under Riba, tactics were not abstract. They were codified into rules of thumb:

- When the opponent defends crosscourt with height, step in early and take the next ball down the line to open the court.

- Serve patterns are planned in mini-sets: deuce side slider into the forehand to set up the next ball to the backhand corner; ad side body serve to block the return and then go behind.

- On clay, never donate the short ball. Lift heavy crosscourt until the feet stop, then change direction with conviction.

Training in Spain also stretched her problem-solving off court. New language, new friends, new weather, and a mother managing life logistics created a small, resilient unit. The move demanded adult skills that juniors often avoid: booking practice courts, keeping school on track, building a support network. That independence shows up later when a player has to adjust mid-match without looking to the box for answers. For a broader Barcelona lens, see how Sánchez-Casal shaped Murray.

For texture on this chapter, Tennis.com profiled her Barcelona base and Riba. One coaching voice, two training cultures, and lots of red clay.

The reunion effect: continuity without stagnation

In mid-2023, Riba stepped away to coach Coco Gauff and later returned to Zheng’s team at the end of that season. Reunions can be awkward in sport when a player has grown in the interim. This one was productive because the shared language never changed. Riba already knew the cues that calmed Zheng’s tempo and the drills that raised her rally tolerance before big events. Zheng, in turn, returned with more match scars and a clearer sense of what she needed from a coach. The net effect was continuity without stagnation. For context on that coaching tree, compare how the Mouratoglou Academy shaped Gauff.

The 2024 calendar then had a clear aim: deepen on clay, sharpen first-serve percentage on hard courts, and clean up the plus-one forehand selection in pressure games.

How the choices show up in big matches

- Australian Open 2024: the defensive transitions that Barcelona emphasized allowed Zheng to reset points against pace, even if Aryna Sabalenka’s first-strike tennis proved too heavy in the final. The lesson was useful: the forehand needed more height options under stress.

- Paris 2024 Olympics: pattern discipline plus a high-strike forehand paid off in Olympic match play at Roland-Garros. The gold medal capped a run where she protected her serve with clearer patterns, absorbed pressure on the backhand wing, and trusted the heavy crosscourt ball to earn shorter replies.

- Top 5 in 2025: consistency across surfaces is hard. The Beijing habits matter here. Sleep, nutrition, treatment, and film do not care if the tournament is a 1000 event or a 250. Zheng’s ranking rise was the logical outcome of a routine that travels.

Lessons families can copy without moving continents

You may not have a visa for Spain or a slot at a big academy. The principles still scale. Here are four decisions worth borrowing, with how-to detail.

1) Know when to change environments

Changing environments is not a reward. It is a tool. Move when the old place can no longer stress the right part of the game.

Actionable test:

- If your child is top two in every session and wins most practice sets while repeating the same errors, the environment is too easy.

- If the coaching conversation has stalled at “move your feet” rather than specific fixes, variety is missing.

- If there is no access to different surfaces across the year, planning is handcuffed.

What to do:

- Add a three-week block at a different club or region first. Treat it as a prototype before relocating.

- Set one clear objective for the block. Example: lift the rally tolerance on clay to seven balls before changing direction, or push first-serve percentage above 62 in live sets.

- Keep a simple scoreboard in a notebook. Results are fine, but track controllables: first-serve percentage, return depth past the service line, forehand unforced errors on neutral balls.

Why it works: environments change behavior faster than pep talks. New rivals, new drills, and new coaches force attention.

2) Balance school and relocation like a project manager

Zheng’s mother moved with her to Barcelona. That is not always possible. The principle is to treat school and life as part of player development, not as a separate headache.

How to do it:

- Build a weekly calendar that blocks fixed class times first, then tennis, then recovery and homework. Non-negotiables go in ink. Hitting partners and extras go in pencil.

- Use a 90-day trial rule for any new setup. At the end, review against prewritten criteria: academic progress, physical health, and whether the player still enjoys hitting serves at 7 a.m.

- Decouple the idea of being all in from skipping education. Elite programs can integrate online coursework with on-court time. The stress is lower when both are planned.

Why it works: certainty reduces mental noise. Teenagers invest more energy in practice when logistics are not chaotic.

3) Program surface-specific blocks, not surface tourism

Zheng’s Barcelona years were not photo ops on clay. They were months of repetition. Families can replicate the structure.

How to plan it:

- Schedule at least two clay blocks of 4 to 6 weeks each year for developing juniors, ideally in spring and late summer. Playing three clay tournaments inside those blocks is better than scattering them across the calendar.

- Assign a theme to each block. Example: raise rally length on clay, or master the forehand drop shot only when the opponent defends deep behind the baseline.

- On hard courts, run a mirror block that focuses on first-strike tennis: serve location charts, plus-one patterns, and second-serve aggression. For a practical starting point, try this 30-day forehand plan.

Why it works: grouping reps by surface builds pattern memory. It also conditions the legs and lungs for different demands.

4) Use coach continuity and culture to build pro-ready habits

The point of working with one lead coach across environments is shared language. Beijing and Barcelona felt different, yet the cues stayed the same. You can create that continuity at home.

What to implement:

- One annual theme: pick a single identity for the season. For a big forehand player, it might be “dictate with depth before direction change.” Every practice and match debrief references it.

- A red-yellow-green system after matches: red for habits that broke under pressure, yellow for items that wobbled, green for what held. Review in ten minutes, not an hour.

- A monthly video session: three clips of errors, three of successes. Label the clips with the same terms your coach uses on court. Language repetition matters.

Why it works: pros do not reinvent themselves every week. They execute a stable plan with small adjustments.

What Beijing taught, what Barcelona added

- Beijing taught Zheng how to swing the same way on ball one and ball 101. It taught daily rhythm: wake, train, eat, recover, repeat. It taught respect for craft over hype.

- Barcelona added the chess player’s brain to the ball striker’s body. It added patience without passivity, a better return position on clay, and a topspin forehand that travels safely above the net before dipping hard.

Put the two together and you get a player who can win a short, violent rally in Melbourne and a 20-ball exchange in Paris. That is the modern requirement for top five tennis.

A practical checklist for families and junior coaches

- Map the next 12 months by surface. Mark two clay blocks and two hard-court blocks. Grass can be a short pre-season focus unless you live near natural grass.

- Define the single seasonal identity. Write it at the top of the notebook. Say it before practice.

- Build a weekly routine that includes film review and a simple stats line: first-serve percentage, return depth, forehand errors on neutral balls, backhand crosscourt conversion when on balance.

- Choose one lead coach and two trusted assistants who will echo the same terms. If you try a new academy, brief them on the language you already use.

- Schedule three practice matches a week during blocks. Use the same balls and court surface as the next tournament to reduce surprises.

The bigger takeaway

Zheng Qinwen’s pathway is not a myth about a prodigy. It is a case study in matching environment to need. Beijing supplied the bedrock: clean technique and a professional day. Barcelona supplied the scaffolding: clay volume, pattern literacy, and tactical patience. A reunion with a coach who knew the blueprint made the whole stack sturdier. Families do not need the same passports to steal the same principles. Change environments when the old one stops stressing the right skill. Treat school and life as a planned part of development. Train in surface blocks so patterns hardwire. Keep coach language continuous so pressure does not scramble the brain. Do this for a year and the results will look less like luck and more like cause and effect.

The lesson from Wuhan to Barcelona is simple and demanding: build the player you want by choosing the environment that forces those habits today. Results arrive later. They always do for those who plan their way to them.