Belgrade to Oberschleißheim: How Pilic Academy Forged Djokovic

From a war-torn childhood to four formative years near Munich, Novak Djokovic’s path ran through Niki Pilic’s discipline-first academy. Here is what happened from 1999 to 2003 and what parents can learn about timing, pathways, and costs.

The four-year leap that shaped an all-time career

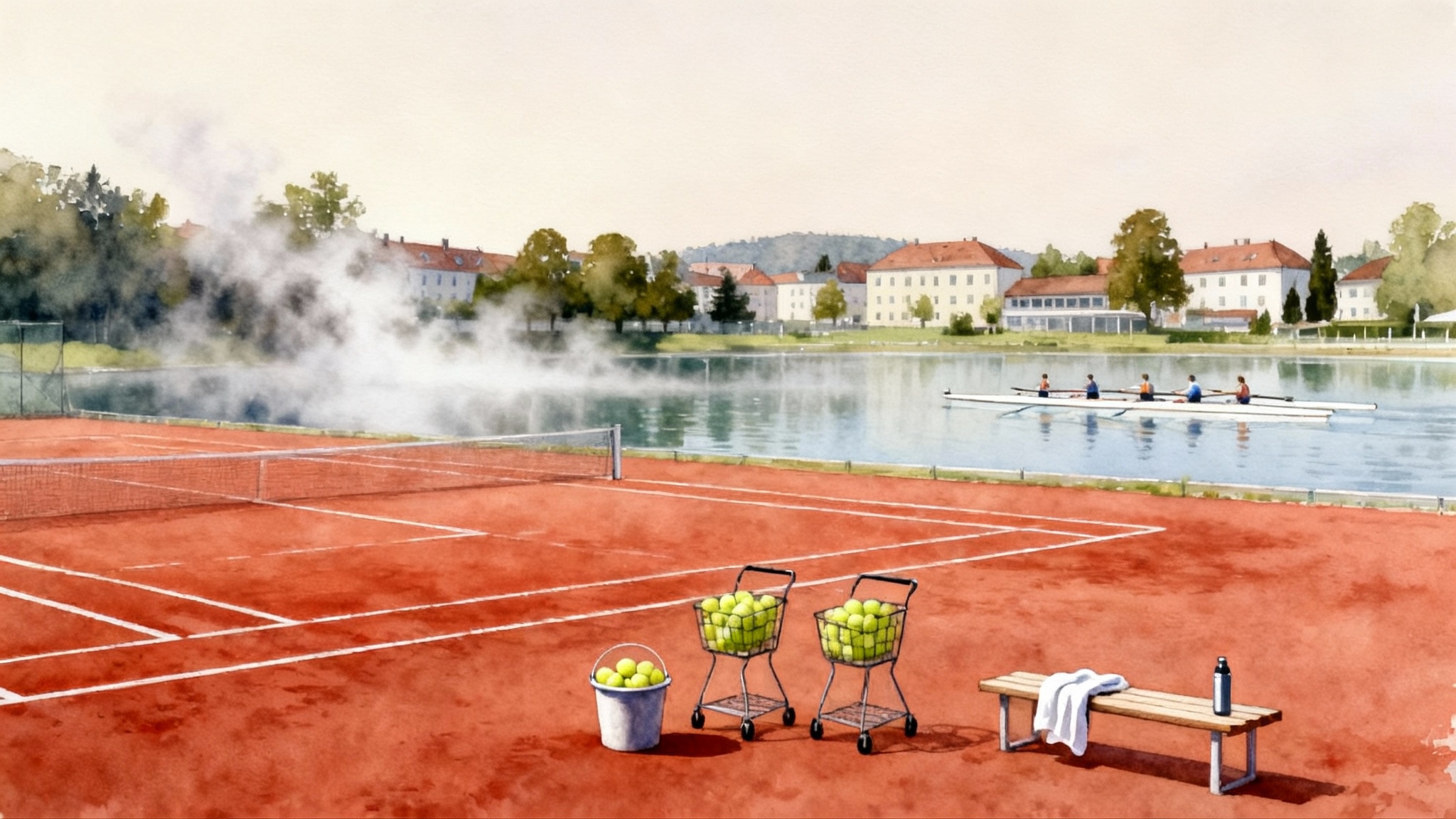

In late summer 1999, a 12-year-old Novak Djokovic left Belgrade for Oberschleißheim, a quiet suburb north of Munich with a rowing basin built for the 1972 Olympics and a tennis academy run by Niki Pilic. The move was a family decision that blended urgency and hope. Jelena Gencic, the coach who first spotted Novak on Kopaonik mountain, told his parents that to keep rising he had to leave Serbia’s limited training environment and face deeper waters. According to Djokovic’s 1999 season notes, he arrived in Oberschleißheim in September 1999 and spent the next four years shuttling between home and Pilic’s courts, stacking seasons of repetition and travel that hardened his game and his resolve.

What emerged from those years is visible in almost every match he plays today: a return that lands deep and central, a rally pattern that asks the opponent to prove they can generate pace without free space, and a stubborn belief that there is always one more ball he can reach.

Why the Djokovic family chose Niki Pilic

Three factors made the academy near Munich the right choice at that moment.

- Trust. Gencic knew Pilic and believed Novak would be treated like a long-term project, not a short-term billboard. Pilic had been a Grand Slam finalist and a Davis Cup captain for multiple nations, so he had the authority to set standards and the network to place juniors in the right tournaments.

- Proximity and stability. Bavaria was close enough to travel back and forth when money ran short or when school demanded time at home. It was also predictable. Flights and trains ran on time, indoor courts existed for winter, and junior events in Germany and neighboring countries offered a dense calendar. A modern German option with a similar practical setup is the ToBe Tennis Academy in Germany.

- A clear philosophy. Pilic’s academy had a reputation for strict routines and for teaching patterns first, flair second. The promise was not quick headlines, it was a reliable base.

Inside the academy: discipline, repetition, and a clear north star

Players who trained at Oberschleißheim in those years describe a simple structure that rarely changed. The day began with footwork and ball feel, not points. Targets on the baseline mattered more than the power meter. Losing a point because you aimed middle third was not a sin. Missing by an inch on a risky line was.

- Footwork ladders, skipping ropes, and shadow swings warmed up the body before a ball was struck.

- Four hours of court time, split across technical blocks and pattern play, built up shot tolerance and depth control.

- One hour of physical work developed elastic strength rather than bulk. Bands, bodyweight, and court sprints were preferred over heavy lifting for young bodies.

- Film and notebook habits. Juniors were asked to write what worked and what did not. Repeatable solutions were prized over miracle shots.

There was also a cultural element. The academy treated time as a currency. Being ten minutes early for a session was normal. Racquets were strung the night before, grips were changed before they tore, shoes were dried and stuffed with paper after rainy sessions. Small signals added up to a larger identity: I am a professional even if I am 13.

This is not a myth. The ATP’s reflection on Pilic’s legacy underscores the academy’s discipline-first identity and notes that Gencic sent a 12-year-old Djokovic to train there in 1999, as reported in Pilic’s discipline-first academy in Oberschleißheim.

What those methods actually built

Discipline is a broad word. Here is how it translated into Novak’s game.

- Depth before angle. Hours of crosscourt and deep middle balls created a default rally ball that lands within a meter of the baseline, usually with modest height and heavy rotation. That ball keeps opponents from stepping inside the court. It looks simple. It is suffocating.

- Return first mentality. Repetition against serves of all speeds trained two commitments: get the ball back deep to the center stripe, and recover balance early. The habit produces the visual you know well, that compact block return that neutralizes even elite serves.

- Long-point breathing. Juniors at the academy learned to treat the fifth shot as the start of the point, not the end. That reframing rewards patience and shape control. The fun part arrives late, when the other player is tired of lifting the ball and gives you a short reply.

- Elastic defense. Band work and light, frequent sprint sessions built a body that bends and springs rather than collides and stalls. Watch Novak slide on a hard court, recover, and reset the point. That is a movement solution born from early emphasis on elasticity.

Resilience by design, not accident

Romantic explanations often miss the mechanism. Resilience came from three practical systems.

- Structured discomfort. Living away from home for months, navigating a new language, and competing every week forces a young player to experience fear, boredom, and homesickness inside a schedule. The calendar does not ask if you feel like training. You train.

- Measurable wins. Pilic’s staff gave juniors clear metrics. Ball targets, serve percentage boxes, and sprint times turn anxiety into tasks. You can hit the second box five times in a row. You cannot control whether a draw puts you against the top seed in round one.

- Tournament stacking with feedback. Novak’s junior schedule in those years mixed national events, regional events, and European championships. Each trip created a loop: test, record, adjust, retest. Small edges accumulate when the loop is tight.

The federation path vs. a coach-led academy

Parents often ask whether a national federation program or a coach-led academy offers better odds. The right choice depends on your child’s profile and your constraints.

Coach-led academy advantages:

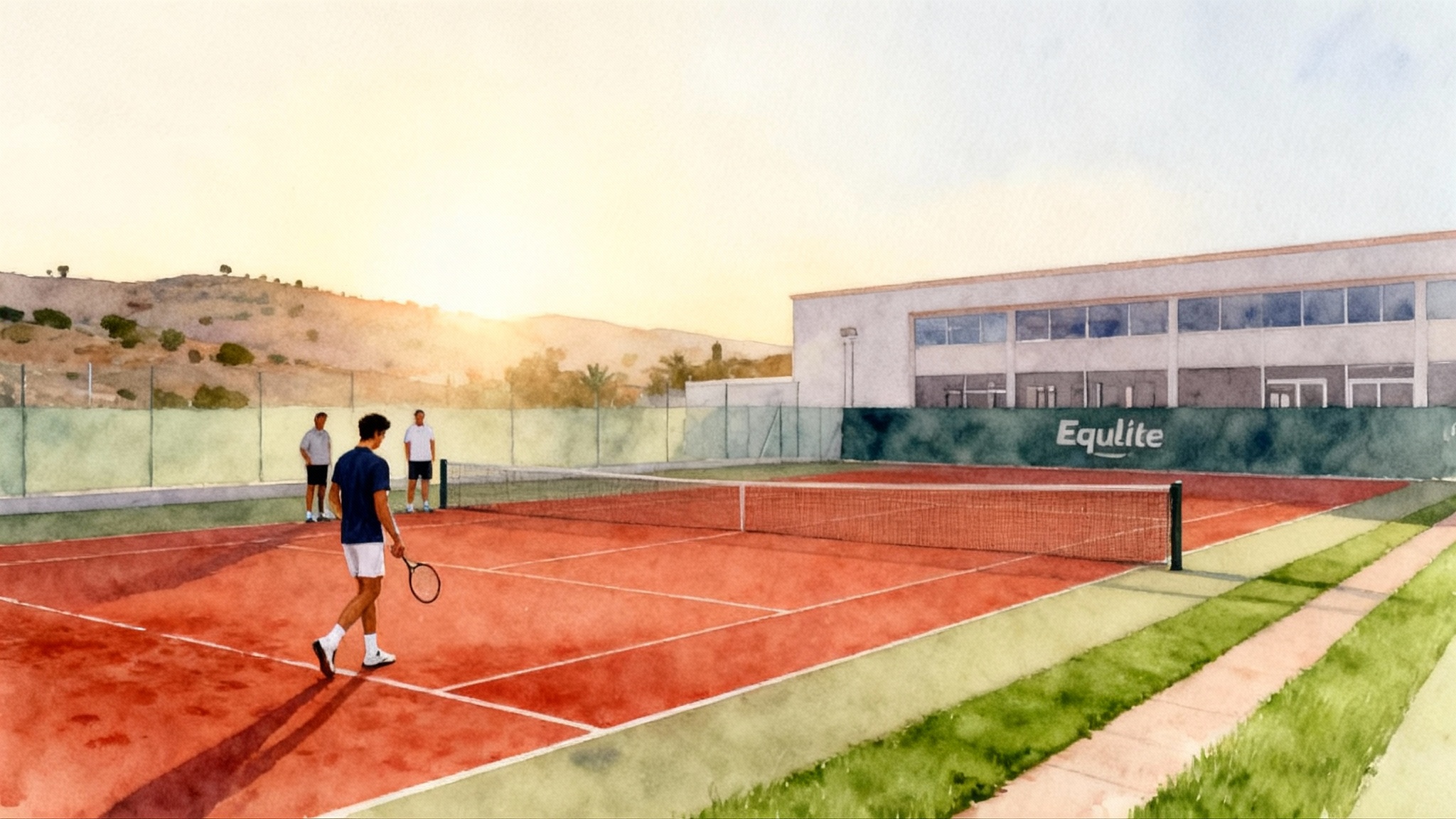

- A single voice sets the plan. Method and message stay coherent across technical work, scheduling, and fitness. Systems like this helped other risers; see Piatti Academy forged Sinner and Equelite built Alcaraz.

- Faster iteration. If a pattern or grip needs to change, it changes this week, not after a committee meeting.

- Market exposure. Strong academies host or attend events where scouts and sponsors gather. That network can be decisive when budgets get tight.

Coach-led academy risks:

- Cost concentration. You are paying for everything, from court time to travel logistics. Scholarships exist but are scarce and often contingent on results.

- Echo chamber. Without federation sparring, a player may face the same styles too often. You must actively seek variety.

Federation program advantages:

- Subsidized resources. Court access, sports science, and physio can be included.

- National identity and team events. Some players thrive inside a cohort with shared goals.

Federation program risks:

- Pace of change. Selection cycles and centralized calendars can slow down technical fixes.

- Role clarity. A federation coach, a private coach, and a fitness coach can send mixed signals if no one is clearly in charge.

A practical rule: if your player needs a holistic rebuild or a tailored fast track, a coach-led academy is often better. If your player already has a stable base and needs volume of matches and services, a federation can be efficient. Reassess every six months.

When to move abroad: triggers, timing, and tests

Relocation is not an achievement. It is a tool. Consider moving when three conditions converge.

-

Competitive saturation at home. Your child consistently dominates local events without being pushed tactically or physically. Wins come too easily, or losses come only from the same unsolved problem.

-

Resource ceiling. You cannot get enough indoor hours, sparring variety, or tournament density without excessive travel from your current base.

-

Personal readiness. Your child can manage sleep, hydration, schoolwork, and basic household routines with limited supervision. If you must constantly prompt them, the move will produce stress rather than growth.

Before committing, run two tests.

- The trial month. Schedule four weeks on site. Demand that the academy provides a written plan for those weeks, including coaching ratios, named coaches, fitness sessions, and match play. Debrief at the end with concrete data, not vibes.

- The reentry check. After the trial, return home for two weeks. Does the player self-initiate the new routines without reminders, or do they slide back? Autonomy is a green light. Dependence is a yellow one.

Managing costs and time away from home

A European high performance setup can cost anywhere from twenty five thousand to sixty thousand dollars per year for tuition and training, not counting travel and accommodation. Costs vary widely by city and by how many weeks you spend on site. Here is how families like the Djokovics made it work and how you can stretch the same dollar today.

- Bundle tournaments geographically. Build four to six week blocks that combine training at base with two nearby tournament swings. This reduces flights and allows for coaching continuity between events.

- Share logistics. Carpool to events with academy families from your region. Share apartments with another family during two-week blocks. Agree in advance on quiet hours and meal plans to avoid friction.

- Buy time, not trinkets. Allocate budget first to court hours, then to a physio or athletic trainer who can screen movement patterns quarterly. Stringing, grips, and shoes matter, but they are small levers compared to time with the right coach.

- Create a travel kit. Two racquets strung for fast courts, two for slow, one emergency backup. A mini tool roll with grips, stencil, dampeners, and a small scale to check racquet balance. A laminated routine card for pre-match and post-match habits.

- Protect school continuity. Ask the academy how they coordinate with teachers. Confirm the weekly study windows in the schedule. A plan matters more than promises.

A sample four-week block for a 13 to 15-year-old might look like this:

- Week 1: Technical rebuild focus at base, four on-court hours per day, one hour fitness, one hour study hall.

- Week 2: Pattern work and practice matches, two match plays with older sparring partners.

- Week 3: Two junior events within driving distance, coach present at one, remote video review for the other.

- Week 4: Recovery microcycle, movement screening, targeted serve work, two days completely off tennis.

What to evaluate in a coach-led academy

Use a scoreboard, not a brochure. Ask for these numbers and proofs.

- Coaching ratio and continuity. How many players per coach on technical blocks, and who exactly will run your child’s sessions. Names and times, not titles.

- Pattern curriculum. Ask to see the academy’s core rally patterns for return, neutral rally, short ball, and defense to offense. If they cannot show their core package on paper, it probably does not exist on court.

- Progress tracking. Request a one-page weekly report with two technical goals, two tactical goals, and two movement goals. Review it every Friday with your child and the coach.

- Tournament planning. Demand a rolling 90-day schedule with target events and contingency events. Look for chess, not checkers.

- Care and education. Who handles minor injuries, nutrition, and school coordination. Meet them before you sign.

Lessons from Oberschleißheim that travel well

The Pilic years were not about magic drills. They were about the mindset that you can build stretch after stretch without glamour and then surge at the right time. Three habits stand out.

- Make the default ball heavy and deep. It is a safe, boring, and ruthless foundation. Build it with targets and track how often you land within one meter of the baseline.

- Treat return as a play, not a reaction. Decide whether the first step is a block to the middle, a chip to the backhand, or a drive to a corner. Then rehearse that choice until it feels like muscle memory.

- Keep a tight learning loop. One pattern to learn, one match to test it, one video review to adjust, and one re-test. The loop turns anxiety into progress.

A checklist before you change countries

- Clarify the primary goal for the next six months and write it down. Improve the second serve kick above shoulder height, raise first serve in by five percent, or add a reliable crosscourt backhand change of direction.

- Confirm that the head coach will attend your player’s matches at least once every two weeks and will deliver concrete notes within 24 hours. Vague praise is not feedback.

- Set a budget envelope for training, travel, and emergencies. Pre-commit which line items get cut first if money runs tight. Do not starve match play to pay for new apparel.

- Agree on a weekly off day. Burnout is expensive.

- Decide how you will measure success. Choose three controllable metrics, like return depth, rally ball height, and second serve double faults per match.

The long shadow of a short window

Between 1999 and 2003, a boy from Belgrade grew into the habits of a professional in Oberschleißheim. The flights home, the winter indoors, the repetition of patterns, and the simple insistence on being early and prepared became the scaffolding of a career that has produced 24 major titles. It is tempting to look for the miracle moment. The Pilic chapter shows something more useful. A family made a hard decision, chose a place with a clear method, and treated each month as a brick. Enough bricks, set with care, become a wall that is hard to climb.

If you are a parent weighing the same kind of decision, copy the part that matters most. Find a coach whose method you understand, test the fit with a trial month, and invest in the routines that travel with your child wherever they play. The exact courts and city will change. The habits you build, like the ones that took shape on court four and court eight in Oberschleißheim, will not.