El Palmar to Villena: How JC Ferrero Built Carlos Alcaraz

The 15-year decision that changed a career

At 15, Carlos Alcaraz left El Palmar, Murcia, and moved two hours up the A-7 to Villena. The choice placed him at a high-performance home base with former world number one Juan Carlos Ferrero and a program designed to compress the years between great junior and real professional. The setting mattered. Villena offered stable sunshine, a compact campus, and a coach who had already climbed the mountain. It also offered a specific competitive on-ramp, including wildcards into the academy’s own Challenger event, and a training culture that forced adaptability across surfaces.

For families and coaches, the central question is not only why he moved, but why the move at that age produced outsized returns. The short answer is alignment. The academy aligned mentorship, tournament access, and a small, integrated team around the player’s growth rate rather than around a generic curriculum.

Early in the move, the academy’s environment gave Alcaraz three advantages that compound over time.

- Calendar control. A centralized base reduced unproductive travel, which freed up weeks for dedicated training blocks.

- Targeted matchmaking. Daily practice with seasoned pros raised his baseline in the same way that scrimmaging varsity accelerates a freshman’s development.

- Pathway leverage. Built-in wildcards and a smart blend of International Tennis Federation and Challenger events let him test up while still banking confidence.

Those levers, used together, help explain how a gifted teenager became a multiple major champion by 22.

Why Villena, and why then

Relocation at 15 can feel radical. It is sometimes the right kind of radical when three conditions are met.

-

Practice quality exceeds what you can reliably arrange at home. In Villena, daily sets with pros and top juniors created the equivalent of live fire. Players learn to read pace, disguise, and decision speed that simply do not exist at lower levels.

-

Coaching continuity increases. Teenagers need fewer voices and more shared memory. A mentor who tracks growth for months rather than days can calibrate loads and tactics with far less guesswork.

-

The calendar bends to the player. An academy with in-house events and relationships can place a player in the right draw at the right time more often than a family working on its own.

Relocation is not a magic wand. It works when the player is ready to leave behind results that come easily, accept tougher daily practices, and handle the social and school adjustments that come with a move. The payback is a higher rate of quality repetitions.

A mentor-driven academy, not a menu of classes

Many academies sell access to courts and a menu of clinics. Ferrero’s model is different. It is mentor driven. Think of it as an apprenticeship layered on top of high-performance infrastructure. The mentor sets the standard of footwork, shot selection, and professional habits. The staff then translates that standard into weekly plans and daily reps.

Here is what that looked like for Alcaraz, and what families should expect if they choose a similar model.

- A single tactical north star. The mentor defines how the player is going to win in three sentences or fewer. For Alcaraz, it was first strike tennis without losing the ability to extend points, plus a willingness to take the ball on the rise.

- Daily live sets with constraints. For example, first four balls must be played inside the baseline, or forehand approach compulsory if the short ball lands inside the service line. Constraints turn style into habit.

- Film over feelings. Post-set review focuses on decision points rather than highlights. Did the player recognize the short backhand to attack. Did he build the point before pulling the trigger.

- Feedback cadence, not feedback volume. One or two actionable points per session, repeated until automatic.

This mentor-first template echoes themes in how Piatti Center forged Sinner and Pilic Academy forged Djokovic, where a clear game identity guides weekly work.

All-surface training blocks, on purpose

The academy’s training calendar rotates surfaces in planned blocks rather than reacting to whatever tournament is next. Families should look for this on a visit. Ask to see last year’s calendar. It should include at least these three elements.

- Clay endurance blocks. Two to three weeks of heavy volume on clay, building point construction, sliding skills, and defensive offense. The aim is more rally starts, deeper patterns, and stamina under pressure.

- Hard court acceleration blocks. One to two weeks sharpening first ball speed, serve patterns, and return aggressiveness. The aim is increasing the percentage of points decided by ball three or ball five on your racquet.

- Short grass tune ups or fast-court simulations. Even if a facility has no grass, coaches can simulate with lower-bouncing balls, slicker courts, and feed patterns that force front-foot movement.

Villena’s climate and layout make this rotation practical. A player can finish a two-hour clay set, eat, lift, and be back on a hard court for serves, all within a few hundred meters. The logistics sound trivial until you add up the conserved minutes each day and the additional sessions that become possible each week.

For a sense of place and programs, explore the Ferrero Tennis Academy in Villena. One page can tell you more about the campus than ten brochures.

The wildcard advantage, used responsibly

Wildcards can prime a career or distort it. The difference is planning. Alcaraz benefited from thoughtful wildcard entries into the academy’s home event and nearby stops. He did not play up for the social media post. He played up when the practice data said he could hold his own in neutral patterns and protect his serve enough times per set. A strong campus with a Challenger on site can magnify this advantage, as seen at the Tenis Kozerki Challenger campus.

At a mentor-led academy, a wildcard is not the start of a new level, it is a test in the middle of a plan. Families should expect a pre-brief and a debrief around each exception. The pre-brief sets a success metric that is not tied to the scoreboard. For example, first serve percentage over sixty five with a plus one forehand to the ad corner on at least half of those points. The debrief returns to those targets before discussing rounds and results.

If you want to see how the local pathway fits together, look up the academy’s Challenger event, known on tour as the JC Ferrero Challenger Alicante. Its timing and field strength show why a home wildcard has real value. Travel is minimal, player routines are stable, and the level is high enough to stress test patterns without throwing a teenager straight into main draws on the full ATP Tour.

A tight support team that grows with the player

When Alcaraz’s results began to spike, his inner circle stayed compact. That is not an accident. The mentor model loses clarity when too many specialists pull in different directions. Here is the structure to look for.

- One head coach who is accountable for the game plan and the calendar.

- One fitness lead who understands tennis loads and can translate the coach’s tactical goals into physical blocks, for example, more decelerations per session to support inside-out forehands from a wider base.

- One physiotherapist who closes the loop between gym and court, and who owns the daily recovery checklist.

- Occasional consultants for serve mechanics or vision training, scheduled in short windows with clear briefs.

Meetings should be short and frequent. Players should hear consistent language across disciplines. Everyone should be able to explain the two or three key metrics for the current block.

Translating the model for families

You do not need a famous mentor to use this approach. You need the structure. Below is a practical checklist to decide if relocation and a mentor-led academy are worth it for your player.

- Film and pattern fit. Watch three competitive matches from the last six months. Count how often your player dictates with a forehand in the first five balls and how often he or she can neutralize the opponent’s first strike. If both numbers are high against peers, relocation into a tougher daily environment can be valuable.

- Practice upgrade, not just quantity upgrade. Write down the three strongest hitters within a thirty minute drive of your current home base. If that list runs out quickly or requires frequent long drives, relocation can unlock many more quality sets.

- Parent bandwidth. Can a parent or guardian spend multiple weeks at the new base during the transition. The first eighty to one hundred days set habits. Families who are present help with sleep, food, and school adjustments so the player can focus on tennis.

- Academy calendar transparency. Ask for last year’s calendar and the next sixteen weeks. If the plan is clear, and surface blocks, testing events, and deload weeks are visible, the academy probably has the organizational muscle to guide a relocation.

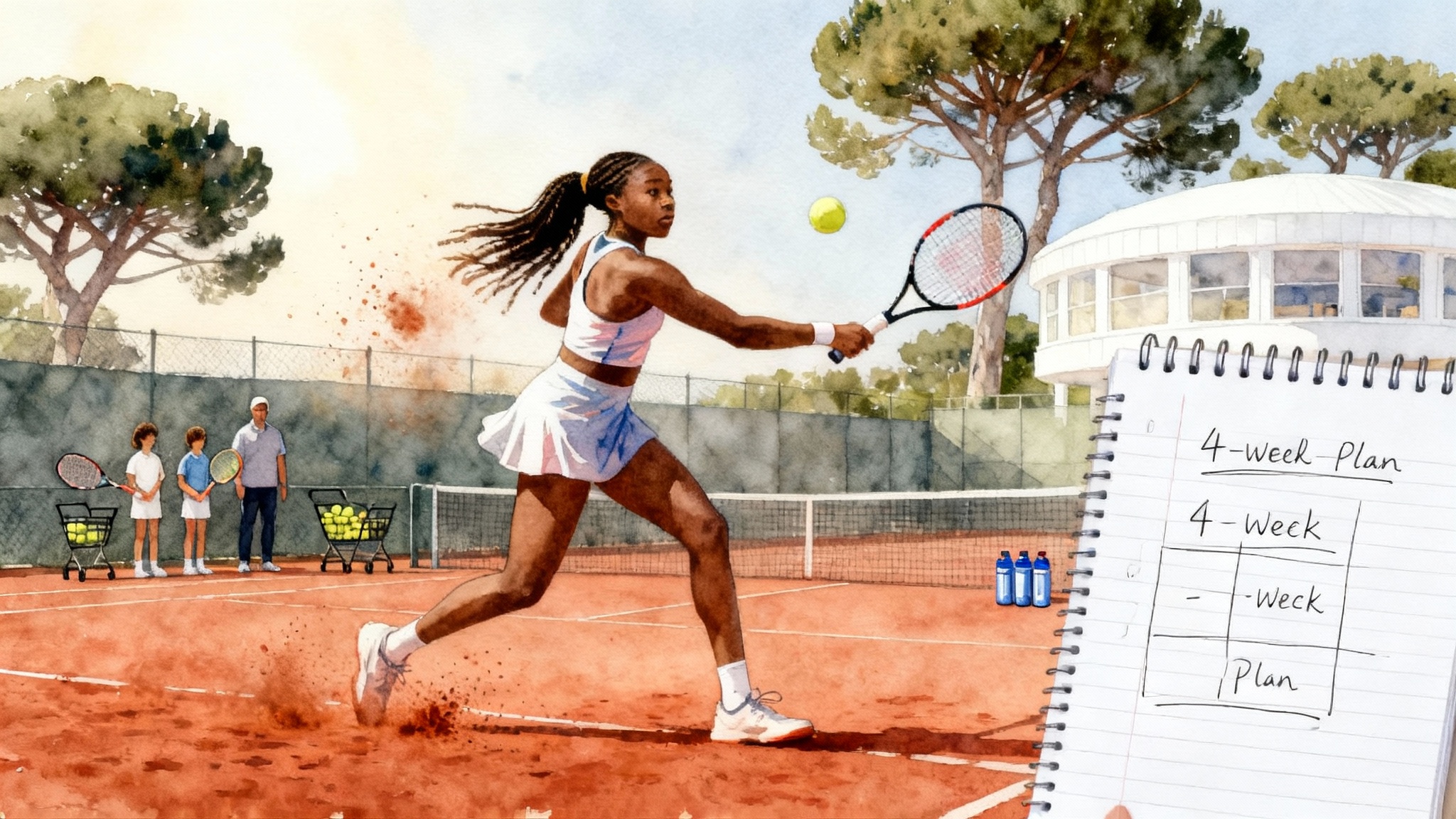

A sixteen week bridge from juniors to pros

This sample plan shows how to combine training blocks, International Tennis Federation events, and Challenger entries for a strong junior transitioning to pro. Adjust weeks to local calendars and school constraints.

- Weeks 1 to 2, assessment and clay base. Two weeks on clay with three live-set days and two technical days each week. Serve targets are fifty first serves into the body on day one, fifty slice wide to the ad court on day three, and fifty flat wide to the deuce court on day five. Match play on day six.

- Week 3, International Tennis Federation M15 or W15 close to home. Singles enters through ranking, doubles is a must since it gives extra serve and return reps with lower emotional load.

- Weeks 4 to 5, hard court acceleration. Focus on return position experiments and plus one aggression. Two days in week five include serve plus two ball patterns starting inside the baseline.

- Week 6, Challenger qualifying attempt or a stronger International Tennis Federation event. Success is defined by holding serve at least eighty percent of service games, not by rounds.

- Week 7, deload and skill polish. Volume drops by thirty percent. Technical micro-goal is a more stable contact height on the backhand when taking the ball early.

- Weeks 8 to 9, clay block and a local International Tennis Federation event. Aim for at least one match where your player wins thirty five percent of return points, a good clay benchmark for a rising pro.

- Week 10, wildcard test if available. A home Challenger or a regional one where travel disruption is low. If no wildcard, choose a strong International Tennis Federation event and double up with doubles.

- Weeks 11 to 12, hard court block with serve and forehand bias. Add daily second serve targets with consequences for misses, for example a sprint or a shadowing drill, to train under mild stress.

- Week 13, Challenger qualifying or International Tennis Federation step up. The main metric is break point conversion rate. Anything above forty percent suggests the player is building points the right way.

- Weeks 14 to 16, mixed surface tune, rest, and review. One week lighter, one week mixed courts, final week planning for the next phase.

This bridge looks simple. It is powerful because it respects recovery, protects development time, and arranges tests at the right moments.

How to judge progress without chasing points

Rankings lag reality. Families need markers that show the game is scaling. Here are five to track.

- First serve plus one success rate. Track how often a planned first serve location produces the expected first forehand. Improvement here is the cleanest sign that patterns are sticking.

- Neutral ball forehand depth. Count balls that land deep enough to force the opponent behind the baseline. An extra one or two per rally changes outcomes against better players.

- Return quality at twelve feet. Place a cone twelve feet inside the baseline. Track how often the first or second return lands beyond that line with margin. Results often follow this number on faster courts.

- Rally start win rate. Tally the first four balls of every point across a match. If you win more of those micro-exchanges over time, the scoreboard will catch up.

- Body language compliance. Define two or three visible behaviors, for example feet set before the return, racquet up in the transition zone, eyes still after contact. Rate compliance in post-match video.

What to ask on a campus visit

If you tour a mentor-led academy, go beyond the marketing deck. Ask these specific questions.

- Who watches my player’s practice sets three days a week, and how will that person communicate adjustments to the rest of the staff.

- Show me last year’s plan for a player who moved here at a similar age. Where did you begin, when did you test up, and how did you define success.

- How many wildcards does the academy influence each year, and how do you decide which players get them.

- Who owns the weekly load spreadsheet, and how do you adjust when school or travel disrupts planned sessions.

- What is your protocol after a good or bad event, and who leads the debrief.

Clear answers reveal a culture that can handle the messy parts of growing a pro game.

Budgeting for the path

Relocation is also a financial plan. Families should model three buckets.

- Fixed academy costs. Tuition, housing, and meals. Ask what is included, especially court time, fitness, and physio access. Clarify private lesson caps.

- Variable travel costs. Build a base case with ten to twelve events in driving range, then a stretch case with four to six flights. Mentor-led models often save money by reducing scattershot travel.

- Professional services. Fitness testing, medical checkups, and equipment. A good academy negotiates stringing and gear pricing for their players.

A rough rule is to avoid cutting the one dollar that saves three. Paying for periodic baseline testing, for example, can prevent injury layoffs that cost weeks of court time and multiple event entries.

The bigger picture, and why it worked

Alcaraz’s partnership with Ferrero lined up three clocks. The biological clock of a growing teenager, the tactical clock of a player learning to construct points against elite pace, and the ranking clock that opens doors. Villena gave him a place where those clocks could sync. The academy did not try to skip steps, it tried to shorten them by making every day look like the tennis he wanted to play on tour.

By the time he lifted big trophies, the style matched the training, the training matched the calendar, and the calendar matched the opportunities. That is the formula families can adapt. You do not need a global name to copy it. You need a mentor who will set a clear way to win, a campus that can feed that plan with daily reps across surfaces, and a pathway that sprinkles in the right wildcards and events at the right time.

Closing thought

Relocation is not about moving away from home, it is about moving toward a system. Ferrero’s academy offered Alcaraz a system that fused mentorship, surface fluency, and a disciplined schedule. If your player is on the edge between great junior and real pro, put your time into those three pillars. Map a calendar, find a mentor who will own the plan, and build a small team that speaks the same language. The results will arrive when the clocks line up.