From Moscow to Cannes: How Elite Tennis Center Forged Medvedev

At 18, Daniil Medvedev left Moscow for Jean-René Lisnard’s Elite Tennis Center in Cannes, then doubled down in 2017 with coach Gilles Cervara and a tight team including fitness coach Eric Hernandez. Here is how that boutique model shaped a Grand Slam champion and what families can learn.

A teenage decision that changed everything

When Daniil Medvedev turned 18, his family made a hard call that many tennis families debate for years. They left the comfort of home in Moscow for the day‑in, day‑out rigor of Jean‑René Lisnard’s Elite Tennis Center in Cannes. In France, training hours got longer, fitness sessions bled into hitting blocks, and the feedback loop tightened. Later, in 2017, Medvedev chose to work exclusively with coach Gilles Cervara, converting a promising setup into a focused project built around one voice and a small, synced team. Medvedev has described that step as a hinge moment for his career, as he detailed in an interview about committing fully to Cervara and the Cannes base: Medvedev on choosing Cervara.

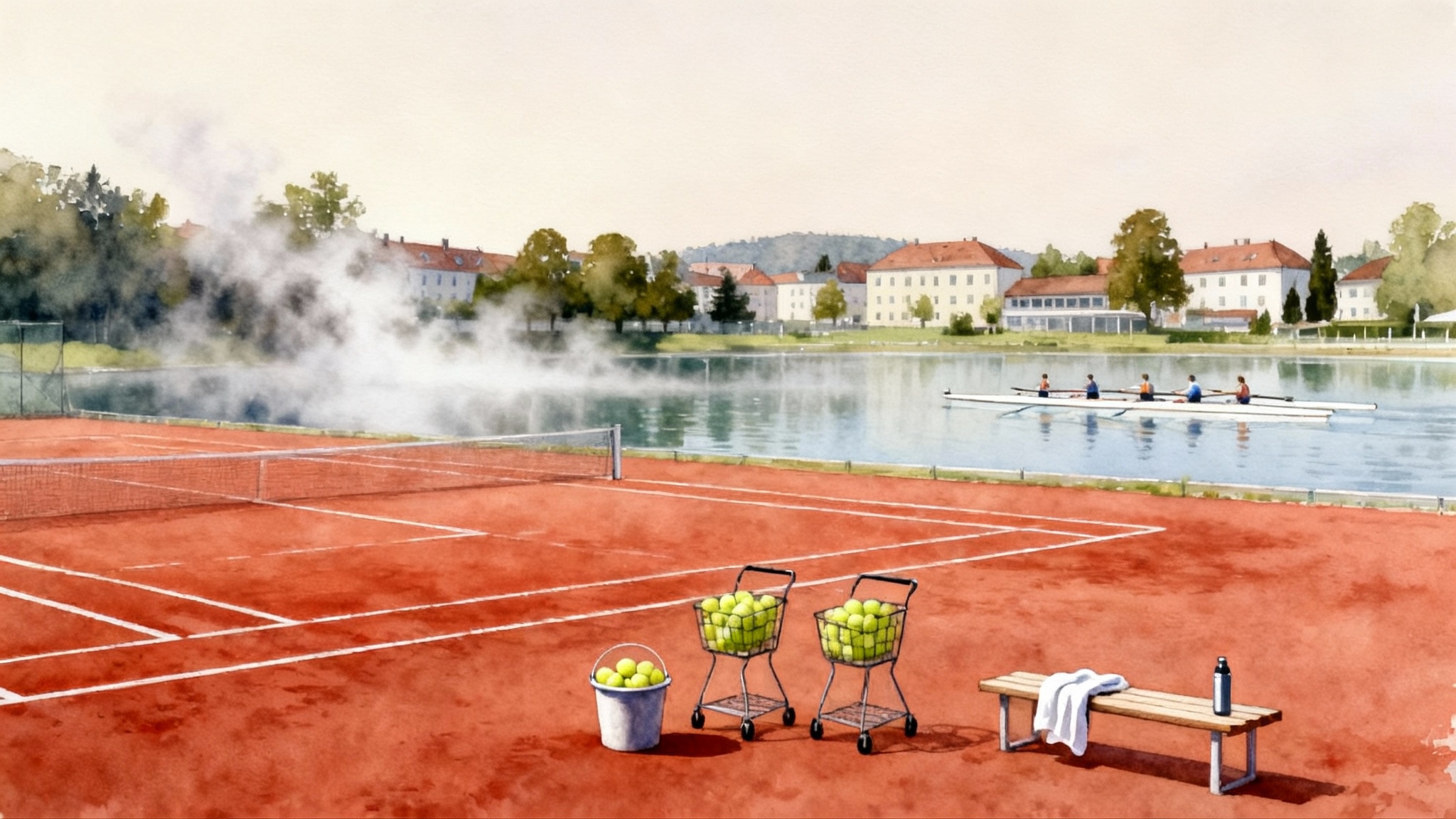

The move was not about palm trees or postcard courts. It was about standard. In Moscow, winter lives indoors for months. In Cannes, the courts and coaches are available, and the level around you is relentless. That is the first real lesson for families: relocation is not a badge or a social media update. It is an answer to a precise performance problem. If your player cannot get the volume, intensity, or sparring diversity they need where they live, then the zip code is now part of the performance plan.

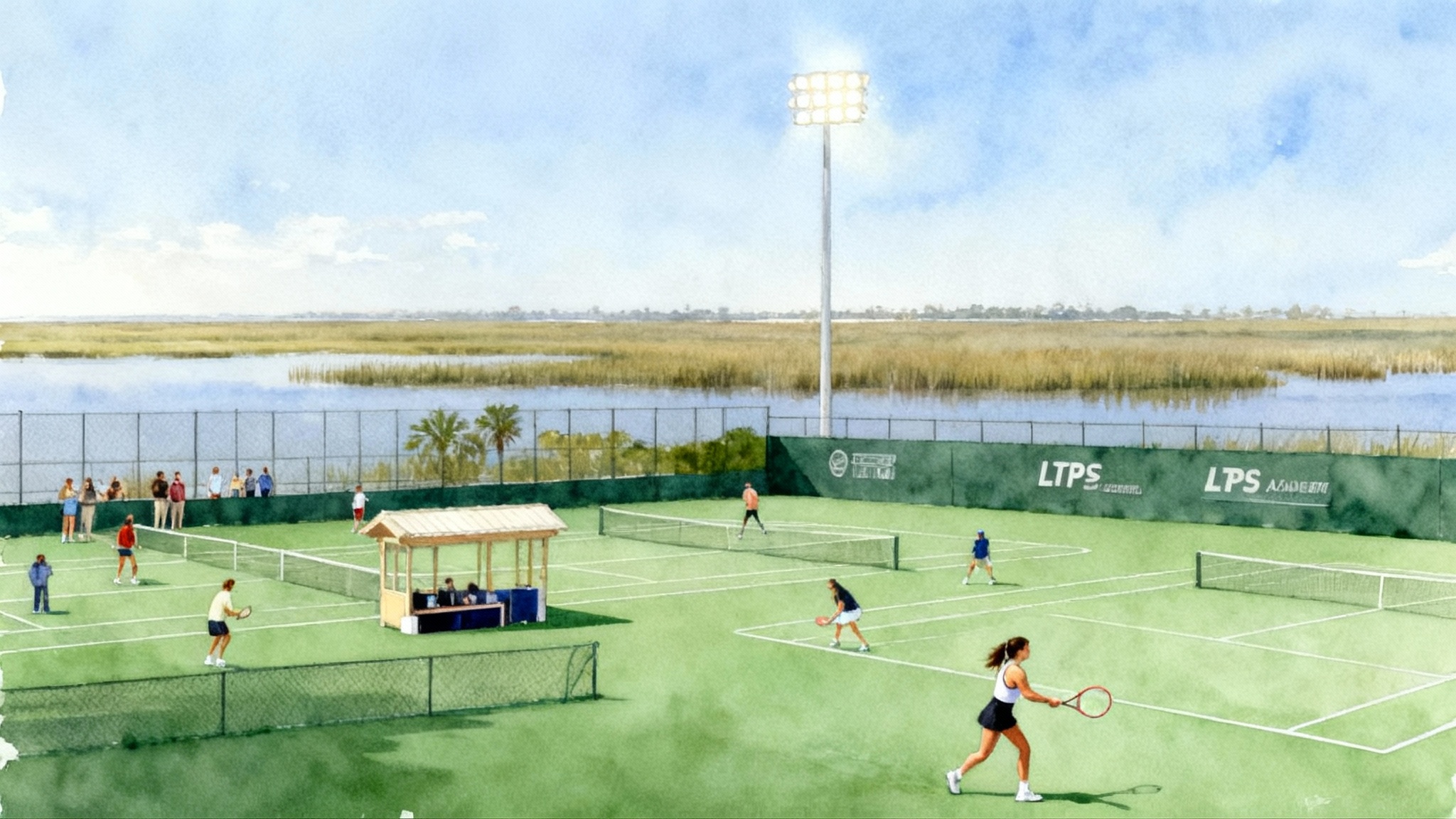

Inside Elite Tennis Center: how a boutique academy actually works

Elite Tennis Center does not try to be everything to everyone. Its promise is narrow and specific: fewer players on each court, more contact time per athlete, and integrated support. You see two players per court as a norm rather than a promotional exception. The staff rotation is coordinated, so a player might start with hand‑fed backhand tempo, slide into a directed baseline live set, then transition straight into footwork and linear acceleration mechanics with the same coaches watching.

In a large, high‑volume academy, it is hard to keep everyone on the same tactical page. In a boutique environment, the same coach who watched a player drift on second‑serve return at 9:30 in the morning can design the afternoon’s footwork circuit to target the first step that caused the drift. That continuity stitches together technique, tactics, and conditioning.

The second structural advantage is shared vocabulary. A boutique academy tends to align on a handful of teaching cues. When a coach says seal the elbow, the fitness coach knows they are trying to stabilize the trunk or adjust contact height. When someone says back fence return, everyone knows this is a deep return position designed to buy time and to neutralize pace, not a passive retreat. The Riviera has several models like this; compare the high‑touch approach to our profile on how All In Academy lifted Andreeva.

The small team around a big game

After 2017, Medvedev’s inner circle got intentionally small. Cervara became the central strategist. Fitness coach Eric Hernandez became the day‑to‑day engine, present not only in the gym but on court, watching how strength and mobility translated into live patterns. This is unusual in tennis. Many players split the worlds: hit with tennis coaches, lift with performance staff. Medvedev’s group blended the two. If the morning focus was absorbing pace on the backhand wing, the afternoon might include shoulder‑external‑rotation work and anti‑rotation holds that mirrored the exact contact he had just rehearsed.

That operating model has three practical parts:

- One leader sets the tactical map for the season and for each tournament block.

- The physical program mirrors the tactical map, so conditioning is not generic. It is in service of specific ball‑striking patterns and court positions.

- Decision cycles are short. Video review, practice design, and match planning happen in the same room, with the same three to four people.

This is how a small team beats scale. When your staff can connect one missed return to a twenty‑minute drill and a week of gym tweaks, the player improves faster because the work is cumulative rather than fragmented. For another boutique blueprint, see how the Piatti Tennis Center and Sinner synced tactics with physical work.

Unconventional patterns, sharpened in Cannes

Medvedev’s tennis looks strange until you put it next to the problems it solves.

-

The deep return position: Standing ten feet behind the baseline on first serve returns is not a defensive quirk. It is a time machine. By backing up, Medvedev lengthens the ball’s flight, which buys him the milliseconds he needs to make a clean, compact swing. The goal is not a winner. It is a neutral ball that lands deep and pushes the server off their pattern. Once the rally starts on even terms, his consistency and redirection do the rest.

-

The flat backhand: Many players talk about taking the ball early. Medvedev takes the spin out instead. A slightly lower contact with a firm wrist and a driving shoulder keeps the ball skidding and fast, denying opponents the jump they want to attack. On hard courts, that skidding trajectory stays inside the lines more often than people expect because his contact is so clean.

-

The inside‑out problem solver: Medvedev’s forehand will never look like a highlight reel. It does not have the whip of Carlos Alcaraz or the heavy arc of Rafael Nadal. What it does have is placement. When he is winning, the forehand is a chalk artist, painting inside‑out and line changes that turn points into geometry problems rather than fistfights.

These patterns did not appear by magic. They were constructed on the Riviera through repetition and honesty. If a pattern broke under pressure, it went back on the whiteboard. If a drill did not touch the match problem, it was cut. The team was ruthless about using the minimum number of patterns to win the maximum number of points on hard courts. Families looking at the French Riviera scene can also explore the All In Academy campus.

Proof of concept: from the 2020 Finals to New York 2021

The test of any training culture is not a single upset. It is whether a player can run the table against the best for a full week. In 2020, at the Association of Tennis Professionals year‑end championships, Medvedev solved three distinct puzzles in succession and walked away with the trophy. The deep return and flat backhand allowed him to neutralize big servers, redirect pace, and control the down‑the‑line change at the right moment. The small‑team model showed on broadcast in the small things: the calm between sets, the specific cueing from the box, the refusal to drift into emotion when a set slipped.

One year later, in the 2021 United States Open final, he stood across from Novak Djokovic, pressure time. The plan was minimalism. Serve to the body for awkward looks, protect the backhand down the line as a bailout winner, absorb the first strike without overplaying. He did not try to be someone else. He did not go for the bravura forehand. He served, he returned, he took away space, and he won in straight sets.

Results like those are never single events. They are the harvest of structure. They are what a consistent practice language and a small‑team feedback loop produce when the biggest match of the year shows up.

Through 2025: a reset, not a rewrite

By late summer 2025, after a difficult run at the majors, Medvedev and Cervara ended their eight‑season partnership. The pivot mattered because the pair had been tied to his rise from a promising top‑hundred player to world number one in 2022. Soon after, Medvedev began working with 2002 Australian Open champion Thomas Johansson and veteran coach Rohan Goetzke, explaining that he wanted to take ownership of what he called his adult career. The official tour feature that covered the change captured the tone of the reset: new voices, same identity. See the ATP feature on new team.

What does not change is the foundation. The habits from Cannes travel. The deep return does not care who sits in the box. The flat backhand is still a geometry tool on hard courts. The practice model that fuses tactical intention with physical preparation remains the simplest way for him to win now.

When should a family relocate

Relocation is not magic. It is logistics and timing. Use these filters before you book tickets.

- Training density: Can your player get four to five quality hitting sessions per week with equal or better sparring partners at home for the next twelve months? If not, relocation is on the table.

- Integrated staff: Will the new base coordinate tennis, fitness, and recovery so that each block supports the same tactical plan? If a site cannot articulate how a Tuesday gym session serves a Thursday return pattern, keep looking.

- Match calendar: Is the new location within reasonable travel time of the target tournaments? A junior who needs frequent International Tennis Federation events should live near a hub.

- Social constraints: Can the family support education and daily life without constant crisis management? A relocation that collapses school or family rhythms will spike stress and torpedo training consistency.

- Financial runway: Price the year, not the month. Count coaching, court fees, travel, physio, and housing. If the budget does not support twelve months, adjust the scope to a shorter, targeted block.

Action step: build a one‑page relocation case. List the home‑base limits that block progress, the specific gaps the new base fills, and a twelve‑month plan. If you cannot write that page in clear sentences, you are not ready to move.

Why a boutique academy can beat scale

Big banners and dozens of courts are not performance. Boutique academies win for certain players because they can do three things better.

- They tighten the feedback loop. The person who sets the tactical plan is the same person who watches the fitness work and the afternoon set play. That speeds up corrections.

- They control training partners. In smaller groups, staff can engineer sparring sessions that target exact problems, like facing a left‑handed slice serve from the ad court for thirty minutes straight.

- They maintain psychological continuity. When the faces stay the same, players are less likely to change patterns under stress.

Be careful: small only helps if the staff is elite. Ask for the coaches’ recent results, not their playing resumes from a decade ago. Watch a live session. If the staff cannot explain the aim of a drill in one sentence, move on.

How to build a long‑horizon support team

Families often treat a player’s team like a shopping list. That wastes money and time. Use a project plan instead.

- Appoint one tactical owner. This is the lead coach who sets the map for the season. Everyone else works to this map.

- Hire a fitness coach who can live on court. The goal is not to lift more weight. It is to connect strength, mobility, and endurance to ball‑striking. Ask whether the fitness coach will watch live hitting and adjust sessions accordingly.

- Add specialists on demand. Mental performance, nutrition, and biomechanics are valuable, but only when they are anchored to the tactical plan. Bring them in for targeted blocks, not as permanent line items.

- Set decision checkpoints. Every four to six weeks, review progress against measurable targets, like first‑serve percentage at 40‑30 in service games or backhand unforced errors against pace. Change the plan only if the data says so.

- Write your exits before you start. Know when a coaching relationship ends and how handoffs will work. If you do not define this, you risk keeping a bigger team than your player can productively use.

What Medvedev’s patterns say about development on hard courts

Hard courts reward clarity. Medvedev’s game is a case study in choosing patterns that scale.

- Neutralize first, expand second. The deep return turns a serve‑dominated sport into a rally game on his terms. Juniors can copy the principle even if they do not copy the distance. Start two feet back, not ten, but make the same commitment to depth and height.

- Build one bailout. Medvedev’s flat backhand down the line is not only a highlight. It is a bailout under stress. Every player needs one high‑percentage exit shot that resets a point without donating free errors.

- Train the change, not the trick. Medvedev’s value lies in how fast he can change direction with the ball. Families should program practices where the player alternates crosscourt defense and down‑the‑line offense within the same rally. You are training the decision, not just the mechanics.

If you already moved and it is not working

Not every relocation sticks the landing. Diagnose before you uproot again.

- Is the player training too many hours without specificity? Cut volume by 20 percent for two weeks and make every drill point‑purposeful.

- Did the team get too big? Pare down to one lead coach and one fitness coach for a month. Let clarity do its work.

- Are results flat because the schedule is wrong? Swap two tournaments for an intensive training week with prearranged sparring and match play. Many players improve more in fourteen quality sessions than in two early‑round losses.

Bringing it back to Cannes

Medvedev’s path from Moscow to the Riviera was not a fairy tale. It was a series of precise choices that a family and a player made together. Change the environment to find the training density that does not exist at home. Choose a boutique academy that can keep the same eyes on you from warmup to cooldown. Build a small team where each person is accountable for outcomes, not just inputs.

He validated that model with the 2020 year‑end championship and the 2021 United States Open. He sustained it into a new coaching era in 2025, changing voices while keeping the same winning patterns. Your player does not need to stand ten feet behind the baseline or hit a backhand as flat as a razor blade to learn from Medvedev. They need to adopt the same design principles: pick a few patterns that fit the surface and the body, train the pieces together, and make small daily decisions serve the big plan.

The map from Moscow to Cannes is not a single road. It is a way of building a career. If you can state your reason to relocate in one sentence, describe your team’s roles in one paragraph, and name the two or three patterns you rely on under pressure, you are already playing the long game.