How Evert Academy Forged Madison Keys into a Grand Slam Champion

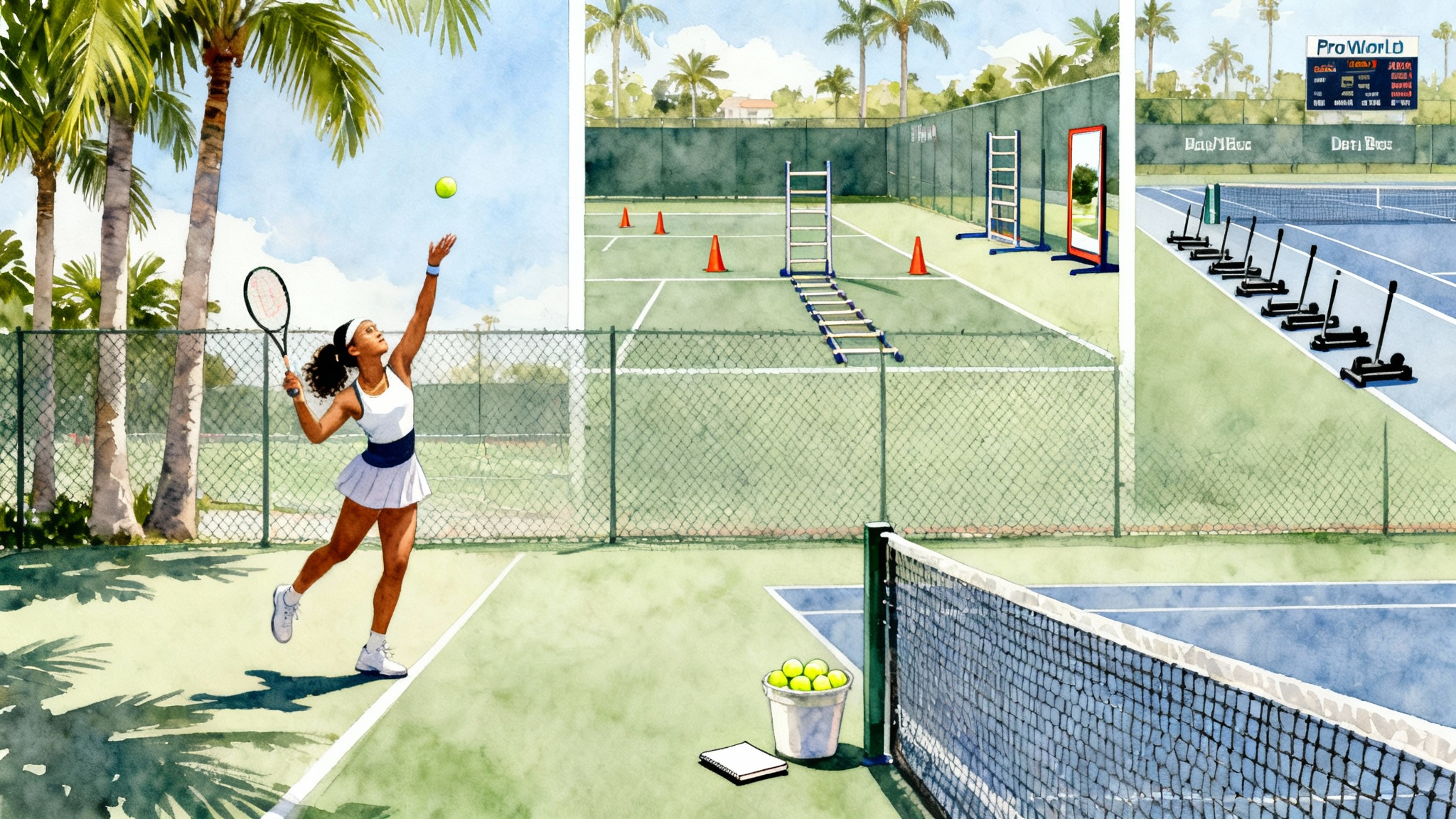

At age 10, Madison Keys left Rock Island for Evert Tennis Academy. The academy’s technical cleanup, footwork-first training, and serve foundations set up her 2025 Australian Open breakthrough. Here is the blueprint parents can use.

The night a plan became a title

On January 25, 2025, Madison Keys lifted the Daphne Akhurst Memorial Cup in Melbourne. Her three-set win over Aryna Sabalenka capped a run that rewired a decade of almosts into a definitive yes. It was the finishing line for a plan that began before she was a teenager, when a Midwestern family decided that if their daughter was going to try this thing for real, they would give her every possible tool to do it. The result was a first Grand Slam, the culmination of technical choices and training habits that had been installed long before she walked into Rod Laver Arena. If you want a single reference point, start with her historic 2025 Australian Open title.

This piece traces how a nine-year-old from Rock Island, Illinois landed at Evert Tennis Academy in Boca Raton, and how the academy’s habits, from technical cleanup to footwork-first training and a second serve with real kick, shaped the champion you saw in Australia. Along the way, we map the key decisions that matter to every family navigating high-performance tennis: relocation timing, coaching transitions, integration with the United States Tennis Association pathway, and schooling.

The move at nine: a family’s decision with a clear goal

The first real decision was not about tactics. It was about logistics. When Keys was nine, the family moved so she could train full-time in Boca Raton at Evert Tennis Academy. That choice pulled together three things parents of serious juniors eventually have to weigh:

- Is the daily training environment strong enough to fix weaknesses, not just praise strengths?

- Will my child be around peers who normalize high standards?

- Can we manage school, housing, and travel without the family falling apart?

In Keys’ case, her parents prioritized the environment. Evert offered year-round volume and a staff that would not be starstruck by raw power. The academy’s director, John Evert, has long emphasized fundamentals and movement as the non-negotiables for scalable power. Contemporary accounts from Florida junior coverage describe Keys as a raw talent who needed technical cleanup and far better footwork, and they document that she relocated to the academy at age nine to address exactly that need. You can see this origin point in USTA Florida’s profile of the Evert Academy at age nine.

For families today, the lesson is not that everyone must move at nine. It is that you calendar the decision around the kid’s readiness to absorb daily, supervised fundamentals. You are not buying prestige. You are buying repetition and correction at scale. For another Florida-based pathway that balanced moves and coaching changes well, study Naomi Osaka’s Florida path.

The Evert blueprint: clean the base before adding layers

When coaches at Evert talk about development, they separate flashy outcomes from root causes. Three root causes mattered most for Keys:

-

Grip and contact foundations. Raw bat speed with extreme grips can blast winners in under-12s and still cap your ceiling later. Early at Evert, Keys reworked how her hands met the ball so the racquet face and contact point could live in a repeatable window. That is what allows power to become a pattern, not a coin flip.

-

Footwork-first thinking. Evert’s training culture lives in the feet. Sessions teach players to see the ball early, take the right first step, choose the correct contact move, and then recover to a neutral spot. If you picture the movement as a train line, the racquet action is the last stop, not the first. Keys learned to organize points with her legs so her forehand and serve arrived on time.

-

Serve mechanics that scale. The goal was not a highlight reel. It was a platform that could hold up when the arm was tired, the wind was up, or the score was tight. That meant a first serve that could hit spots and a real second serve with kick to pull pressure off the forehand.

The common thread is boring in the best way: controllable mechanics that travel. At junior level, this looks slower than kids who slap winners on the run. Five years later, it lets you play offense without making the court feel small.

Footwork-first, explained in plain language

Parents often hear coaches say footwork matters, then watch a practice built around static feeding. Here is what footwork-first actually looks like inside a daily session and how it changes a match.

- First reaction: Train the first two steps like a sprinter’s start. The first step is the steering wheel for the point. A late, heavy first step steals time from your swing and your recovery.

- Contact moves: Different balls require different bases. A wide, heavy ball might call for an open stance with the outside leg loading and driving up through contact. A short ball might call for a step-in move that gets the body weight through the ball. Drills at Evert demand naming the move before hitting, so the feet and brain make the same decision.

- Recovery lanes: After contact, the feet do not admire the shot. They run the racquet back to neutral. The better the recovery, the more often the big forehand arrives on time. When Keys looks comfortable, it is rarely because she is swinging harder. It is because the ball is arriving where she wants it, when she wants it.

Translate that to match day: every heavy crosscourt forehand she hits in the deuce corner is set up by the first step and the chosen contact move. The winner is just the last link in the chain.

Serve foundations and the kick that changed pressure

Young power players often treat second serves like softer first serves. That works until opponents step in and punish the bounce. The change that matters is not only spin rate. It is identity. A second serve with true kick lets the server start rallies on her terms and pushes returners off their strike zone.

Keys built that identity early. She has publicly credited early coaches from her academy years with making the kick serve a point of emphasis, and it shows. The motion generates up-and-across racquet path; the toss lives slightly left of a flat serve; the back leg drives the body up the line of the toss rather than falling away. On pressure points in Melbourne, you could see the effect. Her second serve did not just survive the moment. It created it.

If you are supporting a young player, there are two practical checkpoints:

- Can your child hit a second serve that reliably clears the net by a comfortable margin and still pushes the return above shoulder height?

- Can your child change locations with that second serve without flattening the motion?

Until the answer is yes, the serve practice time should bias to second-serve quality. A safe second serve is worth more than a slightly faster first serve.

Evert’s daily environment: why it suited Keys’ personality

The academy did not turn Keys into a grinder. It helped her become a better version of the player she already was. That matters. Families sometimes fear that a strong academy will sand off a player’s instincts. The healthier reality is that good programs narrow the gap between intent and execution. Evert’s staff is known for organizing work around the player’s A plan, then giving the player the legs and repeatable habits to live that plan against better and better opponents.

For Keys, that meant installing footwork patterns that let a first-strike forehand breathe, shaping a second serve that protected that forehand, and tidying the grips and spacing so the forehand could be accelerated without flying. The environment also normalized ambition. When you are 12 and the court next to you holds a future Division I starter or junior Grand Slam contender, your ceiling gets recalibrated without a speech.

Integrating with the United States pathway

Proximity helps. During her teens in Boca Raton, Keys was able to mix academy work with time around United States Tennis Association Player Development coaches and peer groups, and later with specific national coaches who joined her team during phases of her rise. The practical benefit is simple. You get more eyes, more match play against peers on the same journey, and a clearer sense of where you stand. For another example of a U.S. development network that integrates academy and federation touchpoints, see how JTCC built Frances Tiafoe.

Coaching transitions that honored the base

From the Evert years, Keys added layers rather than switching identities. She worked with a series of respected coaches, including periods with Lindsay Davenport and, more recently, with her husband, Bjorn Fratangelo, who took the lead in 2023. Each phase added something without undoing what came before. That is the quiet power of a sound base. You can update a serve motion, change a racquet, or emphasize patterns without losing yourself.

When she arrived in Melbourne in January 2025, she had modernized her serve mechanics to reduce stress on the body, sharpened her patterns, and leaned into a freer competitive mindset. None of that works without the base she built in Boca years earlier.

Schooling and the life architecture behind the court

Relocation is a tennis choice and a life choice. Keys’ family made it work with a mix of flexible academics and serious boundaries. For parents, three concrete moves help:

- Choose a school option that keeps homework realistic on heavy training days. Hybrids of online coursework and local prep school can work. The measure is not the brand. It is whether the player can train with quality and still show up for academics.

- Protect sleep and nutrition with the same seriousness as stringing racquets. If a player drifts into a permanent 5-hour sleep pattern, the technical work will not hold.

- Commit to anchors outside tennis. Keys’ family life and later her charitable work became ballast. Juniors who last usually have something that is not about rankings.

What parents can copy without moving to Florida

Even if you never set foot in Boca Raton, you can adopt the habits that mattered for Keys.

- Audit footwork weekly. Film two points from behind. Can your child name the contact move used on each ball? If not, build a short list of two moves to master and make that the focus for a week.

- Track serve quality, not just speed. Count second serves that clear the net with margin and bounce above the returner’s shoulder. Log locations hit on second serve. Trade 10 flat first serves for 10 trustworthy seconds. The return on investment is higher.

- Build a feedback triangle. One technical coach, one fitness voice, one parent who only asks process questions. Keep roles clean. If the parent starts coaching grip changes during dinner, the triangle collapses.

- Test the environment before long commitments. Good academies will allow a trial week or a camp block that mirrors the full-time rhythm. Programs like Life Time Tennis Academy make it easier to blend serious coaching with family logistics.

- Measure progress every 8 to 12 weeks. Pick three metrics: first-serve percentage on a specific target, unforced errors on the forehand from neutral, and movement recoveries to a chosen spot. Re-test and adjust the plan based on numbers, not vibes.

- Support late bloomers. Keys’ title did not arrive on the timeline the tennis world projected for her. She arrived anyway. Growth spurts, injuries, and confidence cycles are normal. If the base is sound and the plan is iterative, breakthroughs can come in the late twenties.

Why Melbourne 2025 looked so calm

Watch the final again in your mind. The points that decided the match were not acrobatic improvisations. They were ordinary patterns executed at an extraordinary level under stress. A second serve that kicked away from danger. A first step that set up the forehand. A forehand that traveled to the right part of the court without overhit risk. That is what long-term development buys you. Not magic. Reliability.

It is tempting to tell the story of a single night. The better story is the one that started when a nine-year-old walked onto a hot court in Boca Raton and learned how to move, how to serve, and how to let her big game breathe. The title in January validated the method, but the method was the point all along.

The throughline

From Rock Island to Boca Raton to Melbourne, the decisions stayed consistent. Choose an environment that fixes faults. Build the game on feet and a second serve that holds up. Add layers without betraying the base. Structure school and family so the human grows with the player. Keys followed that path. The trophy was the byproduct.

For parents, the takeaway is simple and actionable. Prioritize environments that make fundamentals non-negotiable. Ask programs to prove how they teach movement and the second serve. Measure progress with clear metrics. Support your child’s timeline, not the internet’s. Do that, and whether or not your path leads through Boca Raton, you give your player something priceless: a game that shows up when it matters.