From Oslo to Mallorca: How Nadal Academy Fueled Ruud’s Rise

Casper Ruud left Norway to base in Mallorca, betting on a clay-first, all-surface program at the Rafa Nadal Academy. Here is how heavy-forehand patterning, work under fatigue, and daily elite sparring turned a top junior into a reliable ATP contender.

The bet that changed a career

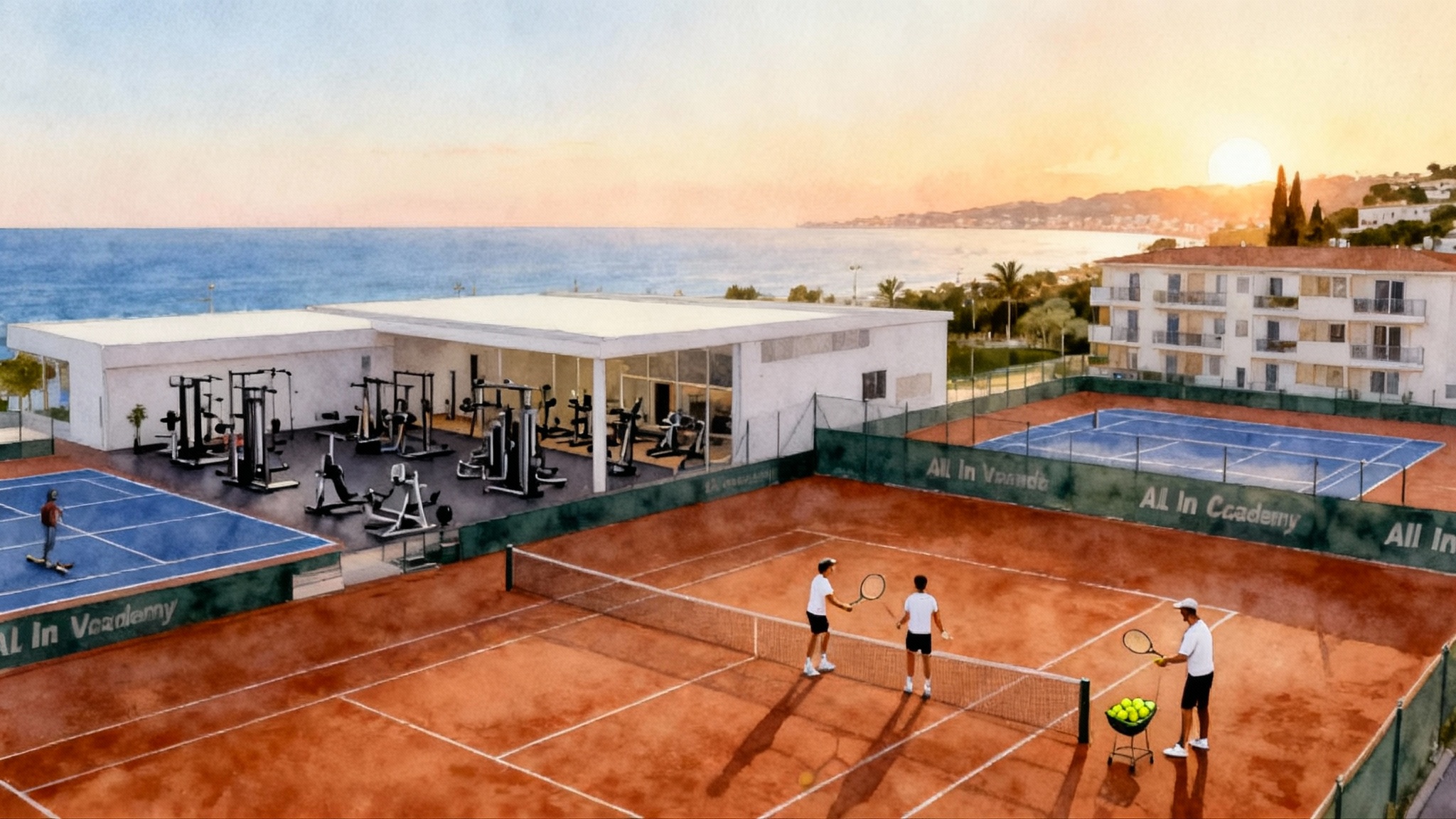

Casper Ruud could have stayed put. Norway had embraced its best-ever prospect, his father Christian Ruud is a former top 40 player, and the national federation knew his promise. Yet the family made a different bet: move the center of gravity to Mallorca, live inside the Rafa Nadal Academy training day after day, and submit to a clay-first, all-surface program designed to harden habits that hold up anywhere.

That decision was not cosmetic. Ruud did not just visit for a preseason. He based himself on the island and, by 2018, committed to building most of his training blocks there. Tournament organizers later described his long connection to the island, noting that he had trained at the academy since 2018. Spain has also perfected this pathway; for a parallel clay-to-hard progression, see how JC Ferrero’s Equelite built Alcaraz.

Clay first, all surfaces always

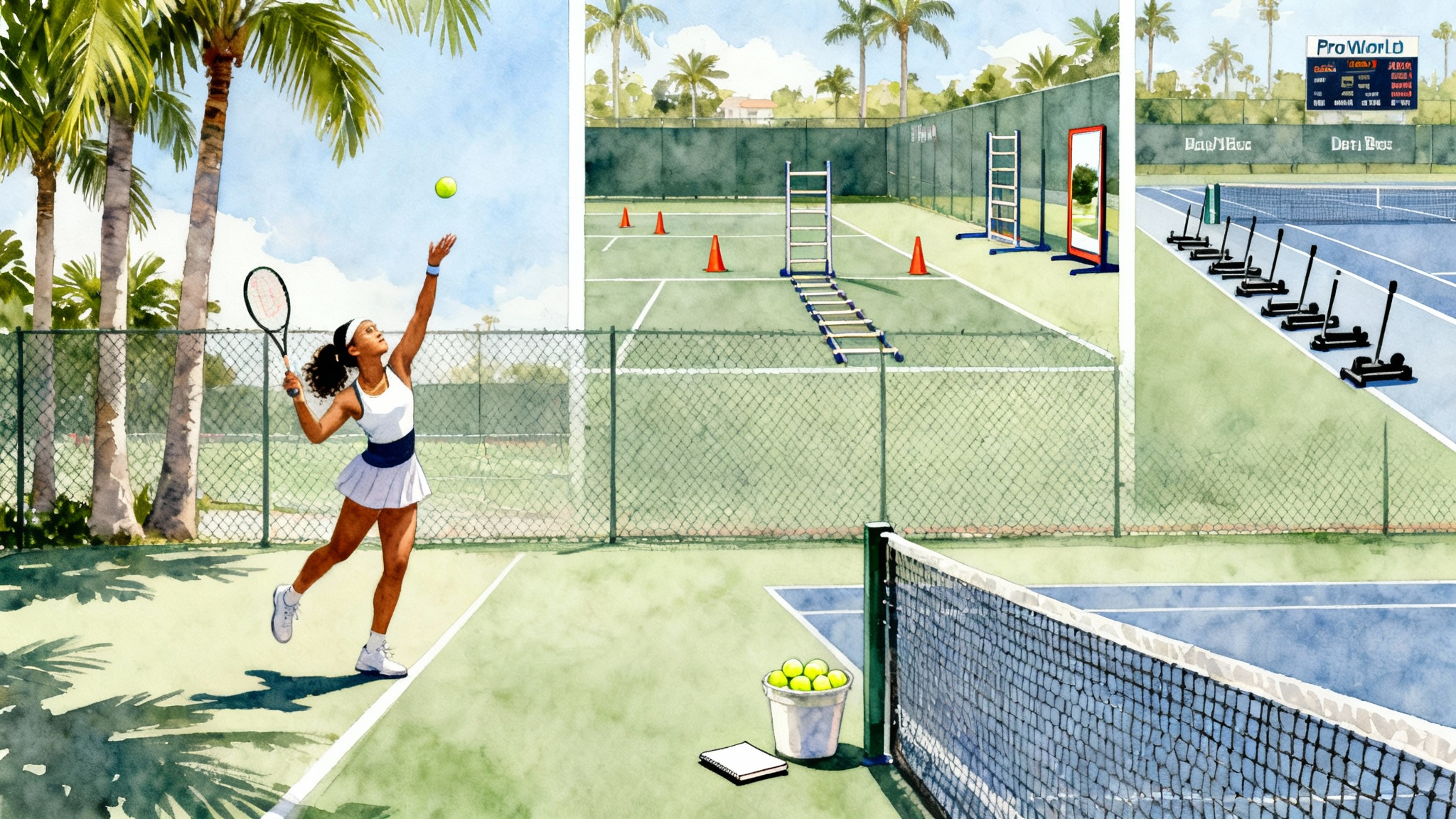

The academy’s blueprint starts on red clay. That matters even if you chase points on hard courts. Clay stretches rallies, forces footwork to be honest, and punishes shortcuts. On clay you cannot fake your defense, depth, or decision making. Players who can create court position on clay tend to adapt more easily to hard and grass because they already own time and space.

Clay-first does not mean clay-only. The academy schedules transitions to hard and grass with specific targets. Think of clay as weight training for your tactics. When Ruud later played on faster courts, he was not reinventing himself. He was applying familiar patterns with a little more first-strike urgency. We have seen similar cross-surface transfer in France, where Mouratoglou Academy shaped Tsitsipas.

The three pillars that accelerated Ruud

Every academy markets a philosophy. What separates the Rafa Nadal Academy is how specific the court work becomes. Three pillars show up in almost every block.

- Heavy-forehand patterning

In Mallorca, the forehand is not a showpiece. It is a system. Sessions ingrain two families of patterns:

- Cross, cross, change: build direction control with two heavy cross-court forehands that lift three to four feet over the net, then change direction to the open court only when the feet are set and the ball is above hip height.

- Serve plus one: wide serve on the deuce side, recover with a shuffle to take the first forehand inside the baseline, then either inside-out to stretch the backhand or inside-in if the opponent cheats. The key is not speed but repeatable height, spin, and depth.

- Repetition under fatigue

Most players drill well when fresh. Ruud’s jump came from repeating decisions when tired. A typical block finishes with two or three sequences at a heart rate you could not hold in a match for long. The goal is not to survive but to maintain the same height over net, depth window, and footwork rules. This is where clay exposes shortcuts and where habits are forged.

- Daily sparring with tour-level hitters

The academy’s depth means a Tuesday practice can feature a player who won matches at the Association of Tennis Professionals (ATP) 250 level and a Wednesday can bring a junior Grand Slam champion. You learn to play your patterns against opponents who do not give you neutral balls. That friction removes the illusion of progress that comes from beating familiar practice partners at home.

What a Mallorca training block looks like

Long blocks are the quiet heroes of development. Ruud’s team structured three to five week segments that look roughly like this:

- Week 1: Clay base. Volume and clarity. Two tennis sessions most days, one strength session four days per week. Forehand patterning is daily. Serve location ladders start on day three.

- Week 2: Clay to hard transition. One session per day moves to hard, with the second session remaining on clay. Point starts become structured: plus-one patterns, backhand depth holds, and transition forehand approaches.

- Week 3: Hard court consolidation. More live points, fewer fed-ball blocks. Serve plus first ball is tracked, and return depth goals are set.

- Optional Week 4 or 5: Match play and taper. Two or three practice sets every other day with specific constraints, like playing every backhand up the line if the opponent drops short, or taking every forehand from inside the baseline with height above the tape.

This rhythm respects recovery. It also frames improvement as a chain, not a pile of random sessions. If the serve location ladder stalls, the team scales back forehand work to find energy for serve mechanics instead of trying to do everything.

Sports science without the lab coat

You do not need a science degree to build evidence-based progress. The academy’s support team uses tools families can copy at home, even without an on-site lab.

- Session rating of perceived exertion: after each hit, the player rates how hard it felt from 1 to 10, then multiply by minutes. This number trends over time. If a session with 300 ball contacts used to feel like an 8 and now feels like a 6, fitness or efficiency improved.

- Heart rate and movement: a simple watch records minutes spent above the aerobic threshold and the peak rate during pattern drills. The target is not maxing out every day but seeing that quality survives when the pulse climbs late in sessions.

- Video at 120 frames per second: a smartphone on a tripod is good enough. The coach checks three checkpoints on the forehand: contact height relative to the net tape, torso rotation range from load to contact, and whether the player lands balanced enough to take a recovery step before the opponent hits.

Force plates and advanced sensors exist, but they are not required for the core job: make the forehand and serve repeatable, under pressure, with recoveries that set up the next ball.

Coaches and continuity

Ruud kept his father Christian as the anchor while integrating academy coaches on site. That continuity matters. It keeps language consistent. It also ensures the long-term plan survives a bad practice or loss. There is a reason many academy relationships fade after the first honeymoon month: without one voice steering, the player collects mixed cues and progress slows.

The Mallorca program solved that by defining roles. The home coach owns the north star. The academy team owns execution in the block. Feedback loops run daily, and video provides receipts. When Ruud’s team later discussed his improvement on faster courts, academy coach Pedro Clar put it plainly: he has become more complete and proactive without losing his base identity. Clar explained Ruud’s evolution in terms of a stronger return, more backhand range, and a more assertive baseline position.

How the clay base translated to results

Results tend to lag the work by months, sometimes a year. Ruud’s foundation on clay did two things that travel to every surface:

- He learned to create time: high, heavy forehands that buy a half step for recovery. On hard courts that same ball clears the tape safely and lands deep enough to push opponents back.

- He earned first strikes: once the serve location settled, the first ball became a forehand more often. That means more rallies start on his terms, which reduces unforced errors born from panic.

Consistency became his calling card, but not the passive kind. It was consistency with purpose: a predictable height, depth, and location that made the court feel smaller to his opponents. When he reached his first major finals, that identity traveled with him. It is the same package that finally delivered his first Masters 1000 title. The path was not glamorous. It was procedural.

Should your family consider an overseas academy?

Not everyone needs to move countries. Use this simple decision tree. For a contrasting relocation story, study how All In Academy and Mirra Andreeva managed environment and coaching voices.

Say yes to an overseas academy if at least two of the following are true:

- Your player is consistently dominating the best local and regional practice partners and still struggling to translate it to national or international matches. This suggests the daily practice friction is too low.

- You cannot reliably assemble a weekly schedule with three or more high-level sparring sessions against players who have already won at the national level.

- The player’s strengths require a surface you cannot access often enough. For clay-centric players in northern climates, that is a real constraint.

- The home coaching environment is stable and committed, but the coach wants help to push volume, physical conditioning, and patterning at scale.

Say no, at least for now, if any of the following are true:

- The player’s technique is still in active rebuild on more than one stroke. Volume without stability often locks in compensations.

- The family budget cannot support three to five week blocks plus travel. One two-week tourist stop rarely moves the needle.

- The player has not yet shown the daily discipline to repeat the same high-quality rep fifty times in a row. An academy will not fix that without buy-in.

How to balance federation resources with a private program

National federations can be allies. The key is role clarity.

- Use the federation for: travel grants, exposure to team events, access to domestic wild cards, and periodic benchmarking camps. Federations also help with sports medicine referrals and contact with other national coaches.

- Use the academy for: daily sparring, structured long blocks, and the grind of repetition under fatigue with measurable targets.

- Keep one head coach: whether that is a family coach or an academy lead, make sure only one person has final say on the plan.

- Share data, not opinions: send session logs, video clips, and simple metrics to all stakeholders so disagreements become about facts. This lowers friction and protects the player from mixed messages.

Which on-court metrics signal real progress

Rankings fluctuate. Progress should not. Track these concrete indicators across six to twelve weeks. Each has a practice and a match version.

Serve and first ball

- Practice: hit 60 serves to three targets on each side. Goal: 70 percent in to the target box, with at least 50 percent landing past the service line midpoint. Then run 30 plus-one patterns where the first forehand lands past the service line midpoint with height above the tape by at least two feet.

- Match: first serve points won above 70 percent on clay and 72 percent on hard for aggressive players. If you are a return-oriented player, adjust down a few points. Track how often the first groundstroke after the serve is a forehand from inside the baseline.

Forehand quality

- Practice: during a 20-ball cross, cross, change drill, record the number of balls clearing the net by three to four feet and landing within three feet of the baseline sideline corridor. Goal: 14 or more out of 20 before the change of direction.

- Match: forehand unforced errors per set at 4 or fewer on clay and 3 or fewer on hard while keeping average rally length similar to your opponents.

Return and depth

- Practice: 50 returns per side with the target of landing inside a two-by-two meter box centered on the baseline. Goal: 60 percent or higher. Progress to taking the return from a foot inside the baseline against second serves.

- Match: returns put in play above 65 percent against first serves and 85 percent against second serves at your level, with at least half landing past the service line midpoint.

Rally tolerance

- Practice: play a 15-ball neutral rally where neither player can hit a winner or approach. Count how often you complete 15 balls without breaking your height and depth rules. Goal: 7 out of 10 series.

- Match: measure how many rallies of nine balls or more you win per set. Goal: at least three on clay and two on hard at national junior level, scaling up with age group.

Pressure proofing

- Practice: after a 60 minute session, repeat your first drill of the day. If the quality drops by more than 10 percent, the issue is not fitness alone. It is your ability to keep technique under fatigue. Train that with shorter, sharper sets and clear recovery periods.

- Match: track break points saved and converted. The target is a conversion rate above 40 percent over a multi-event stretch while keeping break points faced per set under four. If you face more, examine serve location reliability.

A template you can copy next month

If you cannot get to Mallorca this season, try a four-week local version.

- Week 1: clay or slow hard court if clay is not available. Two pattern sessions plus one strength session on four days. One live set day with restrictions: all forehands over the tape by at least two feet.

- Week 2: mix surfaces if possible. Start a serve location ladder and log it. Add a return depth target and record sessions with phone video.

- Week 3: two days of match play, one day of patterns, one day of serve plus one. Add sparring partners who play a level above you for at least one session.

- Week 4: reduce volume by 20 percent. Keep intensity. Re-test week 1 drills and compare. Share the data with your coach and, if applicable, your federation contact.

Tools you already own can help. A smartphone, a tripod, a heart rate watch, and a spreadsheet beat expensive gadgets if you use them every day and review the results.

What made Mallorca the right move for Ruud

The academy amplified the right traits. Ruud already had discipline and a clean base technique. Mallorca added density: more tough balls per hour, more decisions when tired, and more sessions where the opponent tried to take his patterns away. That density turned his forehand into a system, his serve into a launchpad, and his mindset into a daily standard rather than a match-day hope.

Plenty of players visit world-class centers. Fewer commit to long blocks, accept the boredom of repetition, and invite daily friction against tour-level hitters. Ruud did. The lesson is not that everyone should move to Mallorca. The lesson is that a clear identity, trained to survive fatigue against serious opposition, travels to any surface and any stadium.

The takeaway for families

- Decide with evidence. If your player’s practice metrics are improving and match performance is flat, look for stronger daily sparring. That can mean an academy block.

- Keep one voice in charge. Integrate academy coaches without creating a committee. The family coach or the academy lead should own the plan, not both.

- Measure what matters. Serve location, first-ball forehand rates, return depth, rally tolerance under fatigue. Scores come later.

Mallorca was not magic. It was a place where the work could be repeated often, against the right players, with the right feedback loops. That is what accelerated Casper Ruud’s rise from standout junior to durable Association of Tennis Professionals contender. Your version may be a different island or simply a different court across town. The mechanism is the same: build a forehand system, train it when tired, and test it daily against people who can take it away. Do that for months, not days, and your trajectory will tell the story.