Naomi Osaka’s Florida Path: ISP, Harold Solomon, ProWorld

How Naomi Osaka moved from Pembroke Pines public courts to Florida academies, building a serve-first, first-strike identity. A practical map of family decisions on rotating academies, homeschooling, and weapon development parents can copy.

From a Broward park to a Grand Slam podium

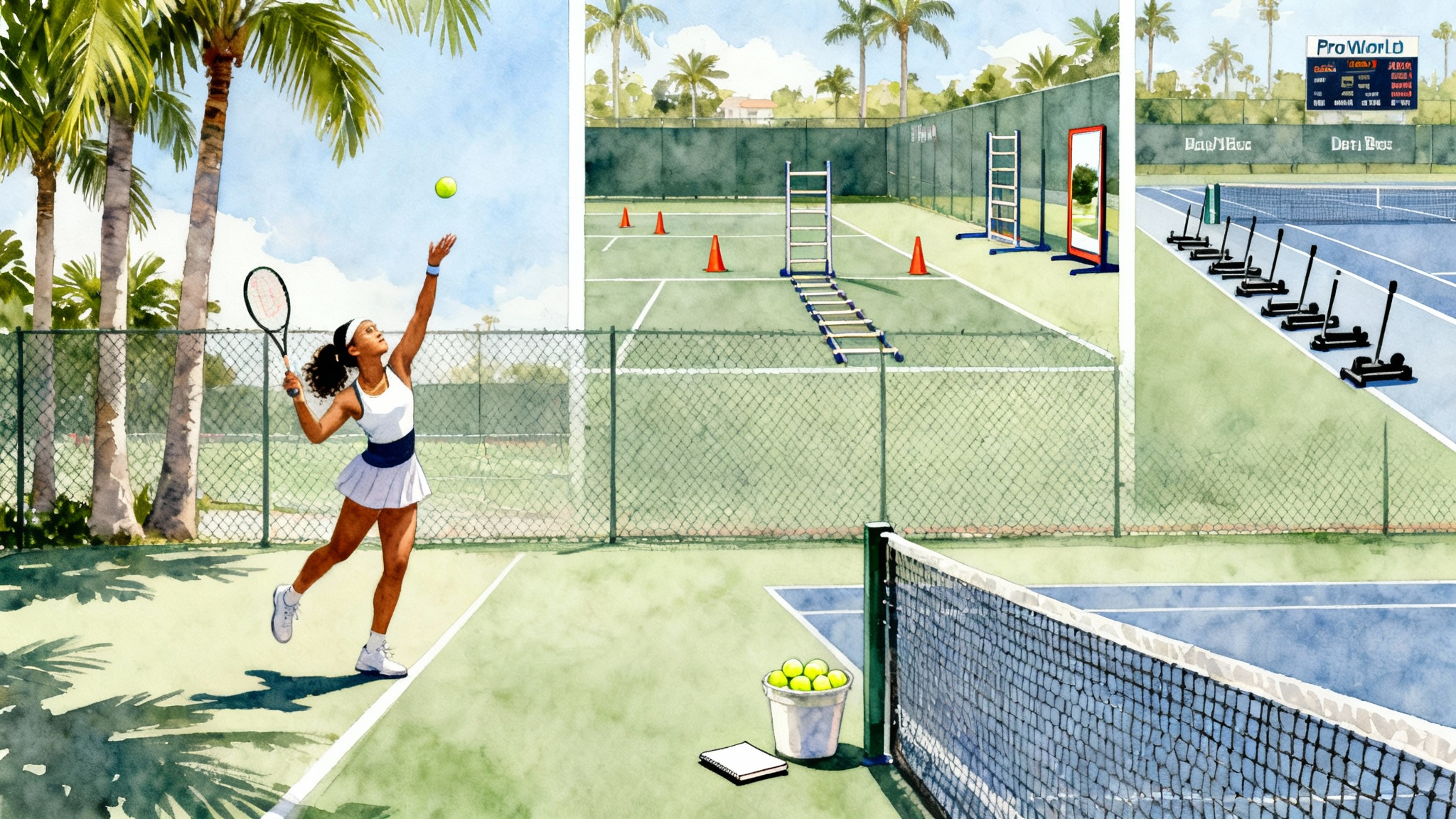

Naomi Osaka’s story is easier to understand if you picture a simple Broward County park. Chain‑link fences. Faded green hard courts. A ball basket that looks too small for the ambition it holds. The Osakas moved from Long Island to Pembroke Pines when Naomi was eight so she and her sister, Mari, could train full time. They trained on the Pembroke Pines public courts during the day and did schoolwork at night, an approach that conserved cash while maximizing court hours. The family’s plan was not to decorate a junior trophy shelf. It was to build a professional game.

That choice explains everything that followed. At 15, Naomi started working at ISP Academy with coach Patrick Tauma. In 2014 she shifted to the Harold Solomon Tennis Academy. Soon after, she trained at ProWorld in Delray Beach. The moves were not random. Each stop added a layer to her serve‑first, first‑strike identity, the game style that powered her rise to world number one and still underpins her post‑maternity return in 2024 and 2025.

Why the family rotated academies

Tennis families often treat academies like one‑time destinations. The Osakas treated them like specialized workshops. When a need changed, the workshop changed.

- Early on, the family needed structure and higher‑end sparring partners. ISP provided both.

- Next, they needed technical tightening and disciplined work habits. Harold Solomon’s program is known for those.

- Finally, they needed a professional fitness base and repeatable point patterns that would scale to tour speed. ProWorld focused on those details.

Rotating programs can be messy without a plan. The Osakas solved this by keeping a constant: Naomi’s father, Leonard, stayed on court as the continuity coach. He was the hub, the academies were spokes. That allowed the family to change environments without changing identity.

Public‑court foundations that travel anywhere

Public courts forced the Osakas to value time and intent. Without unlimited private hours, they ran sessions like a small business.

- A warm‑up that always started on time, no matter how empty the park looked.

- A daily serve block with a target plan, not casual buckets.

- Hitting with Mari to simulate pressure, since beating her sister was Naomi’s first benchmark.

That rhythm transfers to any budget. The main currency was not money, it was attention to specifics.

ISP Academy: pro habits at 15

When Naomi arrived at ISP, the goal was to replace junior habits with professional ones. That started with contact point discipline and a playable first serve. A talented 15‑year‑old can already hit 110 miles per hour. The gap is landing that serve five out of six times and placing it where it hurts.

What changed at ISP:

- Serve targets, not just speed. Deuce‑side wide, body, T, then ad‑side mirrors, all logged.

- First‑ball clarity. If the serve drew a short reply, the next forehand went big to a pre‑called window, not to a vague corner.

- Pro‑style sets. Fewer basket drills, more live sets against older hitters who punished short balls. This punished the wrong choices and rewarded the right patterns fast.

The immediate effect was confidence in short points. Osaka’s big game was no longer streaky. It became a framework.

Harold Solomon Tennis Academy: footwork, discipline, and a sturdier forehand

By 2014, Osaka needed two things that many power players delay: crisper feet and a forehand that held shape at pace. Harold Solomon, a former top five professional and a detail‑heavy coach, built those skills with daily constraints.

- Mirror work and shadow swings to lock in the forehand take‑back, so the racquet path looked the same under stress.

- Split‑step timing on every ball, a metronome for movement. The goal was not more running. It was correct first steps.

- Low‑toss serve reps to clean toss drift, which turns pace into placement.

This is where the first‑strike game matured. The serve drew a predictable ball. The forehand did not leak. The feet got Naomi to the ball early enough to hit on her terms.

ProWorld, Delray Beach: fitness, patterns, and a bigger first strike

ProWorld added the engine. Osaka’s camp emphasized fitness blocks that translated directly to point play.

- Return plus one. If the return went deep middle to neutralize, the next ball went heavy cross to open the court.

- Serve plus one with a fitness tax. Miss the first‑ball window and you ran. Make it, you reset and serve again. The body learned the cost of hesitation.

- Neutral forehands from five feet behind the baseline. If she could drive those balls heavy and deep, the rest of the court felt small when she stepped inside the line.

The academy phase ended with a player who could win without perfect rhythm. If the day felt off, the serve still landed, the first ball still bit, and the fitness engine turned long rallies into opportunities.

The serve‑first, first‑strike identity, explained simply

Think of Osaka’s game like a short math problem:

- Start with a high‑percentage first serve to a precise target.

- Expect a predictable reply. On hard courts, most returns land middle third or short cross when stretched.

- Attack that reply with a forehand to the opponent’s weaker corner. Keep the swing compact and through the court.

- Repeat until the opponent starts guessing. Then aim serves to the opposite target and steal free points.

This sequence does not require 20‑ball rallies. It asks for a serve that holds shape under pressure and a first forehand that does not decelerate. The rest of the game supports those two swings.

The 2024–2025 return through the same lens

Osaka’s comeback after maternity leave in 2024 looked tentative at times, which is normal after a long break. What steadied first was familiar: the serve and the short pattern. In March 2025 she battled back to advance in Miami, saving a key third‑set service game with an unreturnable delivery. The details sounded like a checklist from her academy years. Serve to a spot. Trust the legs. Keep the first forehand decisive. That is not nostalgia. It is a blueprint that scales across chapters.

Lessons parents and juniors can apply this month

Here is a set of concrete actions drawn from the Osakas’ approach. No platitudes, just tasks.

- Choose a primary weapon by age 13, then feed it daily

- If the serve is the weapon, hit 120 quality first serves per day to two deuce‑side targets and two ad‑side targets. Mark a chalk box. Score yourself: 3 points for a box hit, 1 for an in‑box miss, 0 for a fault. Track the weekly trend.

- If the forehand is the weapon, run ten sets of 12 cross‑court drives from inside the baseline. Require the ball to land past the service line with shoulder‑high net clearance. Count how many land in the window.

- Build a serve routine that transfers to match stress

- Always step to the line the same way. Bounce count, breath cue, look at the target, then swing without pause.

- If the toss drifts, stop. Reset. A drifting toss is the main cause of second‑serve fear. Fixing the toss fixes the swing.

- Practice the two‑ball point

- Serve to wide deuce. Forehand to the open court. Reset. Repeat 20 times, then switch to T serve and forehand behind the opponent.

- Return deep middle. Forehand heavy cross. Reset.

- Film one set per week from behind the baseline. Watch feet, not outcomes. Do you split on contact every time?

- Keep school flexible, but visible

- The Osakas used homeschooling to open daylight hours for training. If you go that route, treat school like strength training. Set start and end times, use a checklist, and log hours.

- Protect social skills. Mixed‑age hitting and occasional local events are affordable ways to keep a teenager around peers.

- Rotate academies with intent, not emotion

- Write a one‑page player plan before you audition any academy. Include weapon goals, footwork needs, and a sample week.

- Ask for a trial week with a primary coach and two backup coaches. You are evaluating a system, not a personality.

- Keep a player manual. Save two pages per month: a serve chart, a pattern chart, one video still of forehand contact, and brief notes on fitness benchmarks. When you change academies, hand the manual to the new staff on day one.

- Control costs with structure

- Group sessions can be useful if you insist on specific reps. Ask the coach to earmark 20 minutes for your weapon work inside a 90‑minute group.

- Hire a steady hitting partner two days per week and measure outcomes. A good partner is more valuable than a famous guest coach you cannot afford to see often.

A sample week that mirrors Osaka’s building blocks

- Monday: Morning strength and mobility, afternoon serve plus one. Keep the first‑ball target fixed all week to build trust.

- Tuesday: Pattern day. Return middle, then heavy cross. Film from behind for 20 minutes.

- Wednesday: Footwork intervals. Split‑step timing and first‑step drills. Finish with 30 minutes of neutral forehands from five feet behind the baseline.

- Thursday: Fitness set play, first to four with no ad and a fitness tax for hesitation. If you pull a forehand, add a 10‑second shuttle immediately.

- Friday: Serve targets, second‑serve kick development, and forehand depth windows.

- Saturday: Match play against a variety of hitters. Treat it like a laboratory. The goal is to test Monday to Friday habits, not to protect a score.

- Sunday: Off‑court review. Update the player manual and set three measurable goals for next week.

What Florida provided and how to recreate it anywhere

Florida gave Osaka three practical advantages: year‑round hard courts, a deep pool of hitters, and multiple academies within a one‑hour drive. If you do not live in Florida, copy the inputs.

- Year‑round courts: use indoor time or a weather‑neutral sport court in a driveway for serve reps and shadow swings.

- Deep hitter pool: build a small network. Two steady partners and one older player who stretches your pace are enough. Programs like Gomez Tennis Academy in Naples can model that community feel.

- Multiple academies: you can rotate within a single club by alternating coaches with complementary strengths. Systems like Revolution Tennis Academy in Orlando show how a day‑academy setup can support that rotation.

The quiet power of first‑strike tennis

Parents sometimes fear a first‑strike path because it sounds like gambling on winners. Done right, it is the opposite. You bet on execution, not hope.

- A reliable first serve is less about speed and more about toss and contact height. Those are practice skills.

- A decisive first forehand is less about risk and more about planning where to hit before the serve even leaves the hand.

This is why Osaka’s game aged well. On good days, she looks untouchable. On average days, she still has the two swings that simplify choices.

The takeaway for academy directors

If you run a program, the Osaka path is a reminder to publish exactly what you teach and why. Families will rotate anyway. The best retention tool is clarity. Show a parent how your program will grow a serve that holds under stress and a first‑ball pattern that wins points in under five shots. Then measure it monthly. For a parallel Florida case study in clear systems, see how Evert Tennis Academy shaped Keys.

Conclusion: a deliberate path, not a miracle

Naomi Osaka did not stumble from a public park to Grand Slam titles. Her family picked Florida for volume, then rotated academies for specialization, all while preserving a single on‑court identity. The product is a serve‑first, first‑strike style that travels well and survives time away from the sport. If you are a parent or a junior in 2026, you do not need her genetics or her sponsors to copy the engine. You need a plan for a reliable serve, a decisive first forehand, and a willingness to change environments when those two swings stop getting better. That is not luck. That is management.