From Dolomites to Bordighera: Piatti Tennis Center Forged Sinner

At 13, Jannik Sinner left skiing in the Dolomites for Riccardo Piatti’s academy in Bordighera. We trace how small squads, pro-hitting blocks, and fundamentals powered his rise, then turn it into a family action plan.

A boy from the Dolomites chooses a new slope

Jannik Sinner did not grow up inside a tennis bubble. He grew up in the mountains. Before he learned how to manage the first four shots of a rally, he learned how to pick a line down an icy slope. That matters. Skiing gave him balance, rhythm, and courage. But at 13, he made a decision that would shape his career. He left the Dolomites and moved to Bordighera on the Ligurian coast to train at the Piatti Tennis Center in Bordighera, led by Riccardo Piatti.

Sinner’s choice reads simple on paper. It was anything but simple for a teenager. Leaving a sport he loved, changing schools, living away from home, and betting on an academy that believed in small squads, daily fundamentals, and the steady exposure to professional intensity. That trio is the through line from a red-haired teenager on a side court in Bordighera to a Grand Slam champion who now wins because his game holds up every week, not just on perfect days. For another academy-to-pro example, see how Equelite built Carlos Alcaraz.

Why Bordighera, and why Piatti

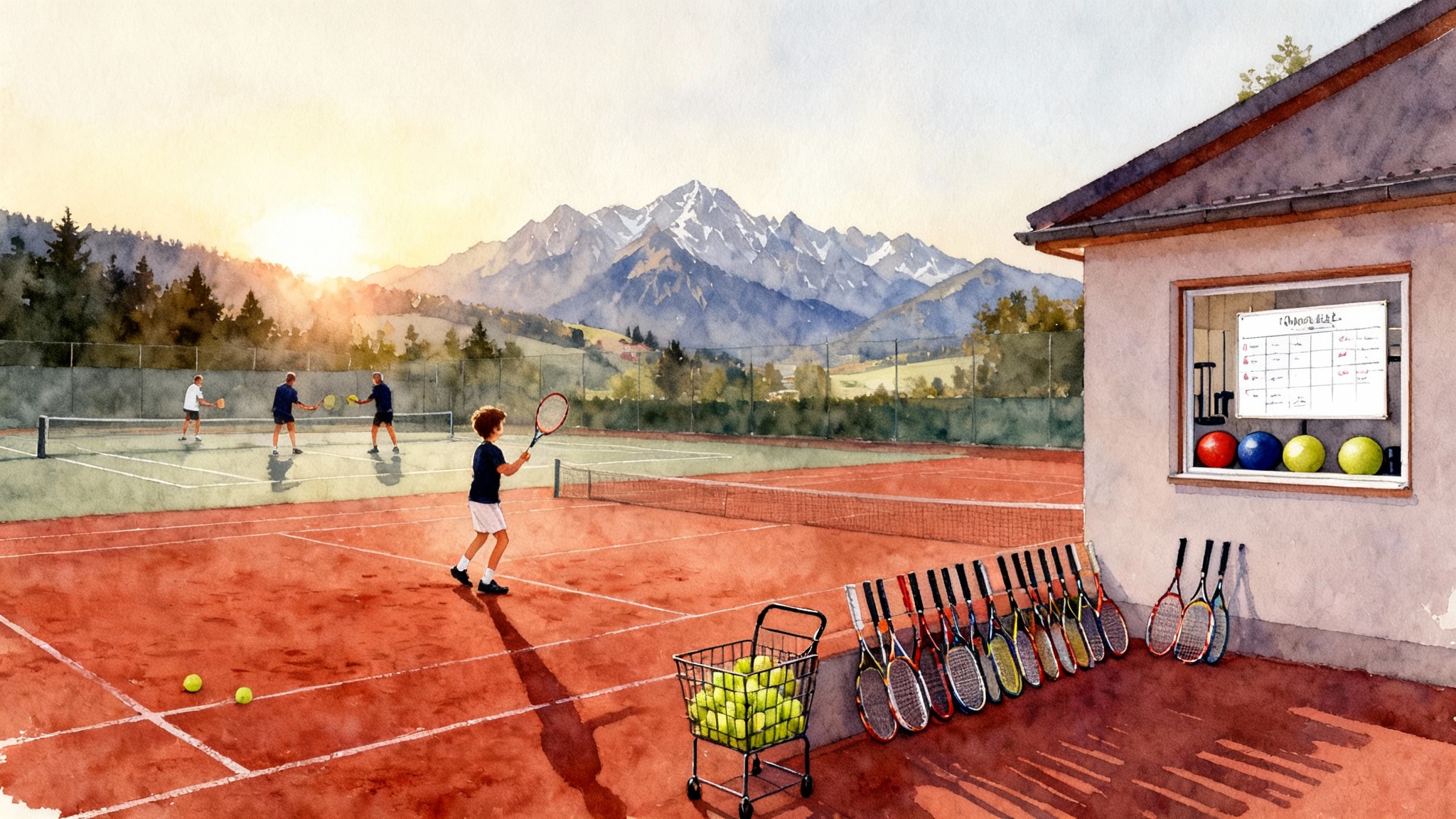

Riccardo Piatti has long been known for meticulous technical work paired with a clear pathway from junior to professional tennis. At Bordighera the environment is compact, the courts are close together, and the staff works with small groups so feedback loops are short. That context created a daily structure where Sinner could live inside the details. The result was not a collection of tricks. It was a stable base of mechanics and decisions that carry under pressure.

Three pillars of the Piatti model stood out in Sinner’s formative years.

- Small-squad drilling: two to four players on a court with a coach who keeps score of details. Not just winners, but depth past the service line, first ball quality after serve, and the ability to neutralize heavy pace.

- Pro-hitting blocks: scheduled sessions where a talented junior faces older, stronger hitters. The goal is not to win practice sets. The goal is to learn the speed of the next level and adjust spacing, preparation, and shot selection to that speed.

- Fundamentals and independence: consistent work on grips, contact point, footwork patterns, and recovery steps, combined with habits that make a player less dependent on constant sideline coaching. Journals, video clips, and goal sheets are part of the week, and players learn to run their own warm ups and cool downs.

Those pillars are not glamorous on a highlight reel. They are the kind of habits that make a backhand down the line reliable in the eleventh game of a fifth set. When you later watch Sinner lean into a return and redirect it cleanly, you are seeing hours of simple, scored patterns from Bordighera. For a Riviera comparison of environments and pro outcomes, read how the Elite Tennis Center and Medvedev aligned process with results.

What a week at Piatti looked like for a rising junior

Every academy has a schedule. The difference is what gets measured. A representative week for a player in Sinner’s lane at 13 to 16 might look like this.

- Monday morning: 90 minutes of drilling in a three-player group. Emphasis on crosscourt forehand with a quality line change every fourth ball. The coach records depth percentage past the service line and notes whether the body stays stacked at contact.

- Monday afternoon: strength and mobility block. Hip rotation, ankle stability, and a short sprint session. Then 45 minutes of second serve plus one forehand patterns, followed by 20 minutes of returns at set scorelines.

- Tuesday morning: two hours with a pro hitter who takes time away on purpose. The junior is told to maintain contact in front and accept a smaller margin over the net. The coach tracks unforced errors that come from spacing mistakes, not ambition.

- Tuesday afternoon: doubles patterns to sharpen the return and first volley. Not a social session. Every drill ends with a point that starts with a specific serve target.

- Wednesday: technical day. Video check for forehand slot and backhand shoulder turn. A footwork ladder is used to pace split steps with the hitter’s contact. Finish with serves to three zones on each side, recorded as makes and misses, not just feels.

- Thursday: another pro-hitting block. The junior must hold serve to 30 and cannot lose a return game by more than two points. If they do, the coach inserts a fed-ball reminder of the missing fundamental, then the points resume.

- Friday: competition set in the morning, recovery and flexibility in the afternoon, and a short classroom session where each player writes the three things that traveled well in the week and the one thing that needs a focused block next week.

In that format the player learns a simple truth. Progress is not random. It is tracked and confronted. If the feet stop on contact, the coach has a clip and a count. If the return floats, there is a goal for contact height and a target on the deuce side that must be hit eight of ten times. Independence grows because the player can describe their own adjustments instead of waiting for instruction.

How fundamentals became a Grand Slam weapon

Watch Sinner in pressure moments and you see the payoff from those years. The serve starts points with clarity. The first forehand does not search for a miracle. The backhand holds direction against pace and then changes down the line when the opponent’s balance opens the lane. The return sits early, on the rise, and it is compact enough to repeat. For career context and results, see the Jannik Sinner ATP player profile.

Those are not magic touches. They are the result of thousands of scored reps where the cost of a lazy recovery step is a lost point on a whiteboard. The small-squad format teaches responsibility. The pro blocks teach reality. The fundamentals keep the body stacked and the swing paths clean so the ball behaves under stress. That is how a player arrives at a first major title and then backs it up with consistent results across surfaces and continents.

The pivotal choices that built the runway

Sinner’s path can be mapped through three big decisions that many families face in their own way.

-

Leaving skiing for tennis. This was a move from a sport where he was already excellent to one where he was a learner again. The lesson for families is to weigh transferable skills. Balance, lower body strength, and rhythm from skiing, or hand-eye coordination from football or basketball, can accelerate tennis development if the new environment insists on fundamentals. Switching is not a reset to zero. It is a reallocation of strengths.

-

Relocating to Bordighera. Moving at 13 required school coordination, housing, and a support structure that kept family close enough while giving the player room to grow. The academy’s daily clarity made that risk calculable. The message is that geography matters less than structure. A move is justified when the new environment offers measurable, progressive work that your current setup cannot match. If you are evaluating options on the French Riviera, compare offerings like the All In Academy on the Riviera.

-

Transitioning from the academy to a new coaching team. As Sinner rose, he left the academy framework and built a tour team with a lead coach, a performance staff, and a plan that fit the professional calendar. The shift was not a rejection of fundamentals. It was an expansion. A tour team sharpened patterns for specific opponents, built strength and recovery strategies for long travel blocks, and coordinated match analysis with scouting.

The theme across all three choices is the same. Each step traded comfort for clarity. Each step was backed by a plan that could be explained to a 13-year-old and to a parent in the same sentence.

A family guide to the big questions

Families often ask the same four questions when they see a story like Sinner’s. When should we move. How do we handle housing and school. How do we evaluate an academy’s day. And how do you plan the handoff to the tour.

1) Timing a move

- Look for plateau signals. If your player dominates locally without being stretched, or if practice quality has outpaced match challenge, the environment may be too small. A move is timely when the next step offers speed and pressure that cannot be replicated at home.

- Demand measurable promises. Before you move, ask the new academy for a written outline of the first eight weeks. It should include how many small-squad hours per week, how many pro-hitting blocks, and which metrics will be tracked. If those numbers are fuzzy, the timing is not right.

- Start with a trial block. Two to four weeks on site, with a coach assigned and a clear plan. Use that time to test both tennis fit and personal comfort.

2) Housing and school logistics

- Decide on living model. Options include boarding with other players, a host family vetted by the academy, or a parent relocation. Teens vary. Some thrive with peers and structured oversight. Others need a parent present, at least for the first year.

- Align school hours with training. Ask the academy for the dominant training windows for your player’s age and level. Build school around those windows, not the other way around. If the academy trains 8 to 10 in the morning and 3 to 5 in the afternoon, look for school flexibility in the middle of the day.

- Make academics concrete. Agree on weekly deliverables with teachers and set a quiet study block in the schedule. Treat it like a practice court booking. It should be non negotiable.

- Plan recovery and meals. Housing should be within a short walk or drive to the courts. Kitchens matter. So does a plan for two hot meals and one snack block around training.

3) Evaluating an academy’s daily structure

- Ask for the ratio. How many players per coach in your child’s core sessions. Small squads of two to four allow genuine feedback and scoring.

- Inspect the pro-hitting pipeline. Who are the regular hitters for your child’s level, and on which days. You want names, not promises, and a calendar that shows those sessions at least twice a week.

- Check the fundamentals routine. Where do grips, contact points, swing paths, and footwork live in the week. Look for a technical day with video and a written focus that carries into the next three training days.

- Demand objective scoring. What gets measured. Examples that matter include depth past the service line, first ball percentage after serve and return, unforced errors per 20-ball rally, return make rate by zone, and serve targets hit by zone.

- Confirm independent habits. Does every player keep a simple training journal. Do they run their own warm up. Is there a post practice routine for mobility and notes.

4) Planning the handoff from academy to tour-level coaching

- Define triggers, not feelings. Agree on concrete thresholds that start the transition planning. Examples include a top 20 junior ranking, repeated success in professional qualifying draws, or a consistent set of practice metrics that meet pro benchmarks for six months.

- Build a six month overlap. Do not snap from academy to tour team. Start with a trial period where the new lead coach visits the academy or travels for select events, while the academy coach remains involved. The player should feel continuity.

- Assign roles early. A tour team is a triangle at minimum. Lead coach, performance coach or fitness trainer, and a data or video analyst who turns match footage into a simple plan. Add a physio when travel volume increases.

- Keep the language. The new team should use the same words for the same fundamentals. If the academy called the backhand drive a lift through the outside of the ball with a tall left side, the tour coach should keep that phrasing. Consistent cues protect confidence under pressure.

Translating Sinner’s habits into daily drills

Parents and young players often ask what to do on court tomorrow. Here are three simple blocks that mirror the spirit of Sinner’s academy work.

- The tolerance ladder. Crosscourt to a big target for three balls, then a controlled line change on ball four. Score only balls that land past the service line. Start at 12 total balls per set and build to 20. This trains structure before ambition.

- The first four. Serve to a corner, strike the first forehand heavy cross, then play the point live. Keep a tally of points won in four shots or less. The goal is not to end quickly. It is to own the pattern.

- The pro pace adjustment. Find a stronger hitter once a week. Tell them to take your time away on purpose. Your job is to maintain contact in front and shorten the backswing. Film five rallies and review spacing mistakes. Then repeat next week.

Each block is simple to score. Each block teaches independent adjustment. If you can name your miss and your fix without turning to the fence, you are on the right path.

What consistency really means

Consistency is often confused with caution. Sinner shows that consistency is built on reliable aggression. He drives through the ball with a clean base and does not part the sea in search of winners. He sets his feet early, he takes the ball at a comfortable height, and he chooses patterns he has drilled a thousand times. The result is pressure without panic. That is the kind of game that survives a poor serving day or a gusty afternoon and still wins in week three of a long swing.

The academy-to-tour story matters here. Bordighera gave Sinner a body of work that could withstand the noise of the professional calendar. The tour team gave him scouting and travel management that let those skills show up more often. Together they turned potential into consistency.

A short checklist you can print

- Two to four players per small-squad session, with names and times.

- Two pro-hitting blocks per week, with confirmed hitters.

- One technical day with video and a written focus.

- Objective scoring of depth, first balls, unforced errors, return make rate, and serve targets.

- A journal with weekly goals and a three line summary after each session.

- Housing within an easy commute, with a kitchen and planned meals.

- School schedule that bends around training windows, not the reverse.

- Six month overlap plan for the academy to tour handoff, with assigned roles and shared language.

If you can check those boxes, you have built your own version of the Bordighera engine.

The map and the mountain

Sinner’s journey from the Dolomites to Bordighera and onto the biggest courts did not depend on a single genius insight. It depended on the right move at the right time, the daily enforcement of simple fundamentals, and the gradual transfer of responsibility from coach to player. Families can borrow that structure. Start with a trial block. Insist on small squads and measurable work. Protect school and recovery with the same seriousness you bring to backhand drills. When the time comes, plan the handoff and keep the language stable. The mountain looks huge from the base, but the map is clear if you look for the right markers. That is the quiet lesson of Bordighera, and it travels far beyond one champion.