From Murcia to Villena: How Equelite Built Carlos Alcaraz

The hook: a split at the top, a method that endures

On December 17, 2025, Carlos Alcaraz announced he was parting ways with Juan Carlos Ferrero, the coach who shepherded him from teen prodigy to multiple major titles. The decision landed just weeks before the 2026 season and the Australian Open. It felt shocking, but it also spotlighted what matters most for elite development: the method behind the rise. Ferrero’s Equelite Academy in Villena did not only coach a star. It built a system that turned a gifted 15-year-old from Murcia into a multi-surface champion. For context on the change, see the Reuters report on Alcaraz split.

This article uses Alcaraz’s move at 15 as the hinge point and unpacks three Equelite pillars that accelerated his jump from junior to world stage: high tempo training patterns, transition and net instincts, and integrated fitness plus rehab. For a parallel look at academy blueprints that scale to the tour, see Piatti’s blueprint for Sinner and Nadal Academy’s integrated model.

Murcia to Villena: the hinge moment at 15

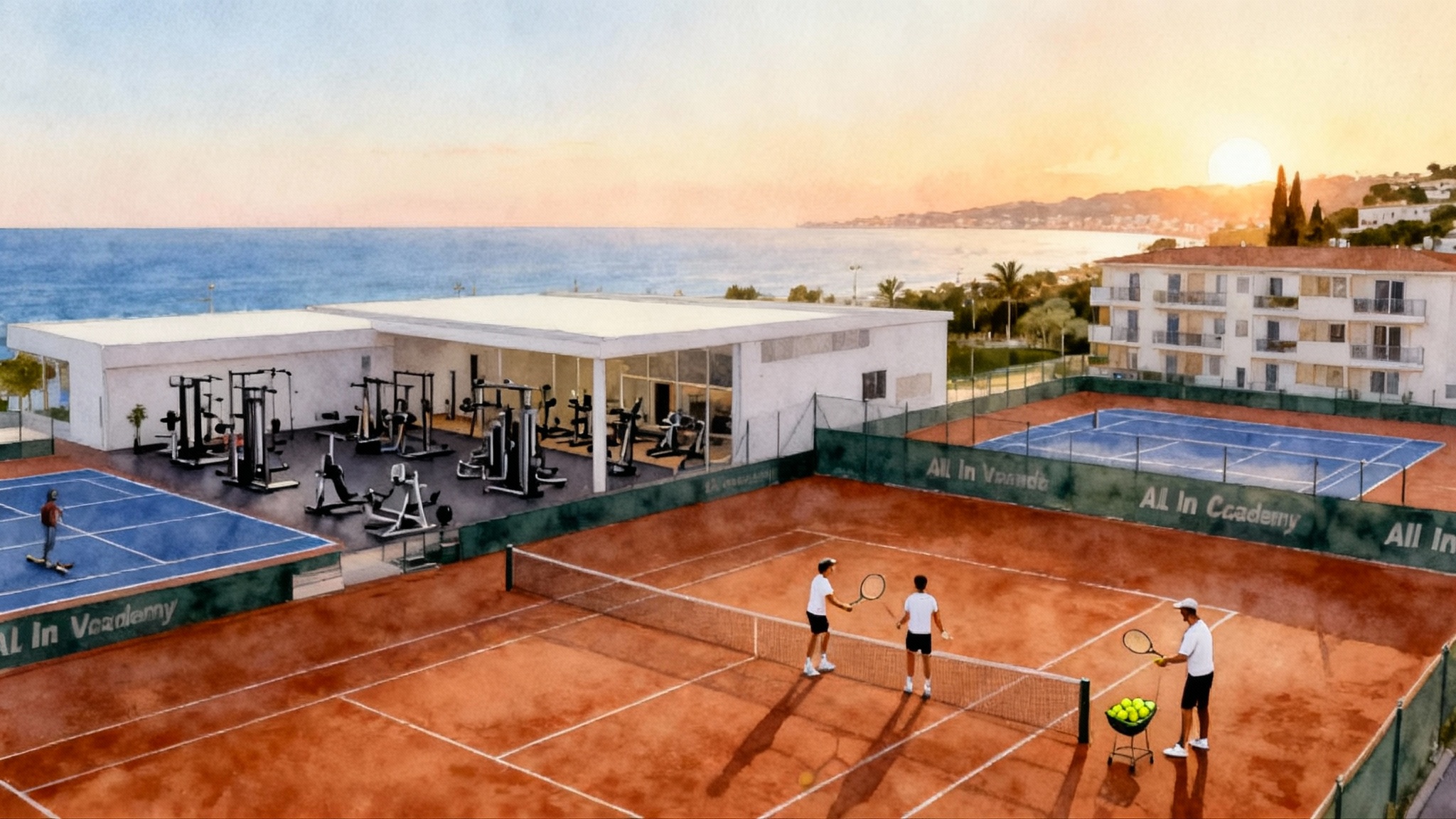

In 2018, Alcaraz left El Palmar in Murcia to live and train in Villena under Ferrero’s direction. That move redefined the center of gravity in his life. Equelite functions like a compact village for tennis. Courts on multiple surfaces sit next to a gym, physio rooms, and player housing. Coaches and staff live on site. The effect is immersion without chaos. Think of it as moving aboard a ship that sails in a straight line every day. Training, school, meals, sleep, and recovery all follow a predictable rhythm.

Families often picture academy life as endless hours on court. Equelite prioritized exact hours, but more important was the repeatable shape of those hours. Each session had a tempo target, a tactical theme, and a physical cue. That structure allowed a teenager to build habits that would survive the turbulence of pro travel.

Pillar 1: high tempo patterns that scale to the tour

Tempo is the hidden spine of modern men’s tennis. Watch Alcaraz at his best and you see quick starts, compressed time between shots, and a first step forward after contact. At Equelite, tempo was not a vibe. It was measured. Here are three patterns the staff used to create pace without sloppiness and to make fast feel normal.

- Serve plus forehand into open court, then recover inside the baseline. The cue was simple: land the serve, split step by the time the return clears the service line, choose direction early, and finish your forehand with the intention to step in. Coaches tracked how many times the player hit the forehand on the rise rather than drifting backward. The outcome was not just winners. It was possession of the middle of the court on ball three and ball five.

- Two-ball pressure sequences. Players hit a heavy cross-court ball, then immediately a line change at a higher contact point. The point of the drill was not the line change itself, it was the decision speed. Coaches set time caps for the second swing path. That constraint forced players to prepare sooner and trust a shorter, more compact backswing under stress.

- Backhand redirect on the rise. Instead of waiting for a plump ball to change direction, the drill asked for a redirect from a neutral or slightly defensive contact. Feet had to be set early. The backhand had to ride through the ball without fear of the opponent’s next shot. This immunized players against being bullied by pace.

None of these patterns look magical on paper. They become powerful when the academy builds a weekly cadence around them. Monday and Tuesday emphasized volume and speed of decision. Wednesday mixed pattern work with serve plus one. Thursday and Friday layered in point play and finishing patterns that demanded better recovery steps. The idea was to raise the speed limit, then teach the body to handle it every day.

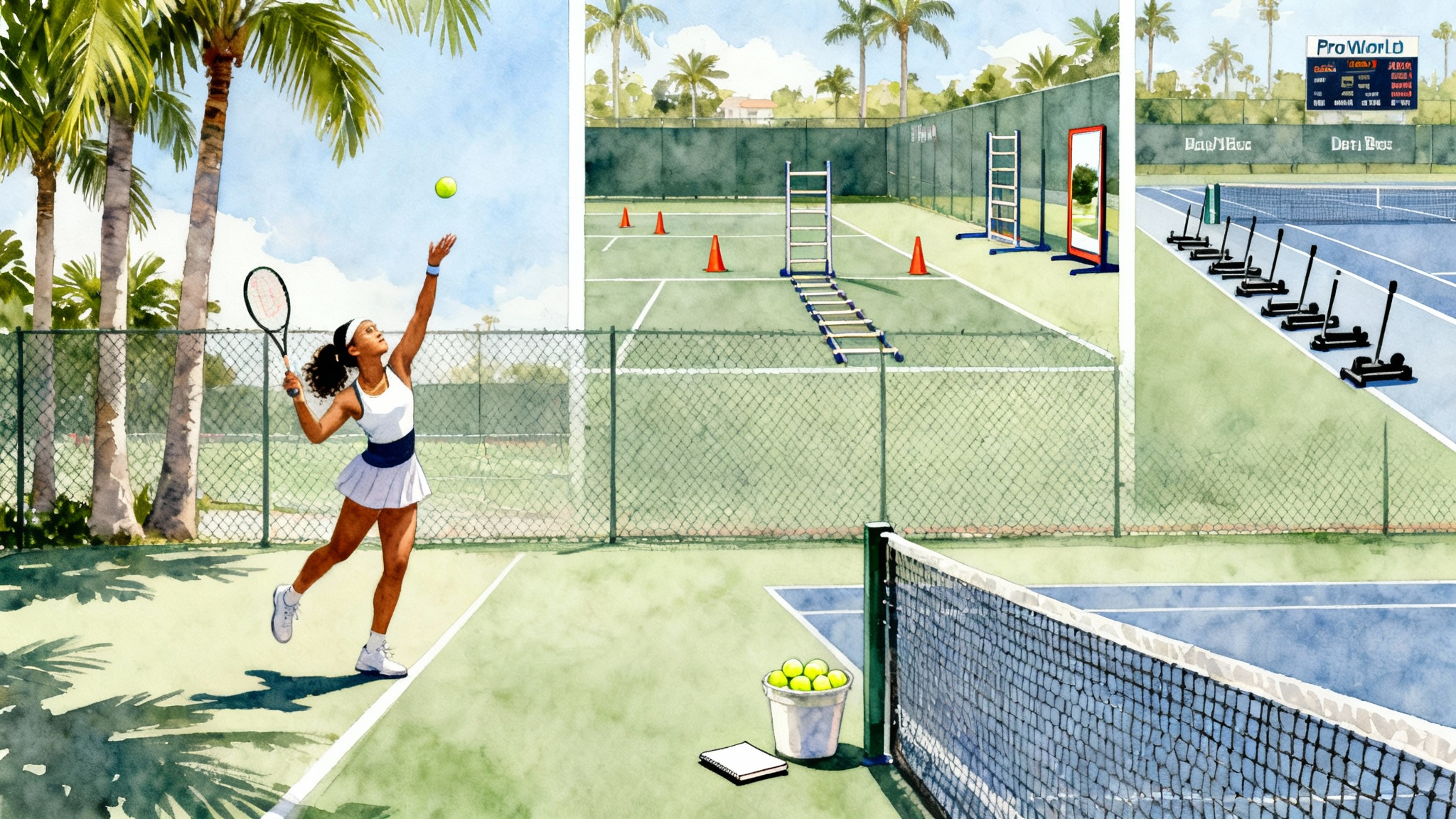

Pillar 2: transition and net instincts as a default, not a bailout

Alcaraz’s brand features drop shots and highlight volleys, but the deeper point is that he treats forward movement as a normal choice, not a last resort. Equelite encouraged two instincts that juniors rarely practice enough.

- The two-touch approach. After forcing a short ball, players aimed to make their approach land deep and heavy, then expect to volley one more time. The first volley was planned as a setter, not a finisher. That mindset reduced panic at the net and promoted better positioning.

- The transition read. Players learned to identify three ball types that trigger a forward move: a short ball after a deep cross-court exchange, a sliced reply that sits up in the middle third, and a floating return after a body serve. Coaches called these out during live drills and demanded an automatic step in. Over time, that recognition became reflex.

These habits mattered later on grass and hard courts, where Alcaraz’s willingness to finish points shortened rallies on fast days and stopped opponents from pinning him to the baseline on slow days.

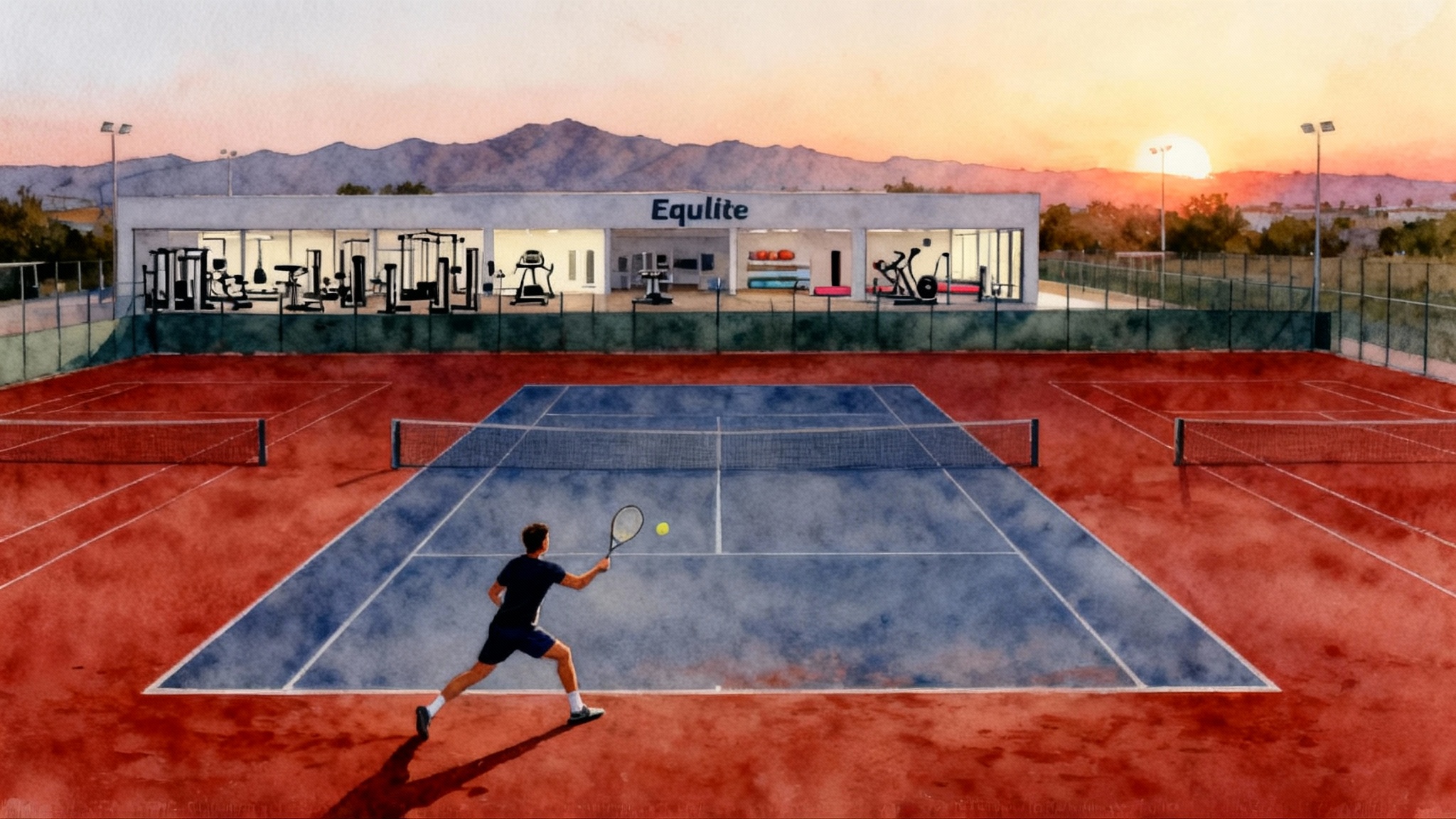

Pillar 3: integrated fitness and rehab under the same roof

Equelite operated with a basic premise. Your body is your calendar. The academy’s gym, track, and physio suite were not add-ons. They were the engine room that let training intensity climb without derailment.

- Testing. Regular strength and movement screens told coaches when to push and when to maintain. For teenagers, the focus was not how much weight they lifted. It was force production and deceleration quality. Could the player arrive fast and still stop on a dime without twisting the knee into bad positions.

- Prehab before rehab. Each week had a bare-minimum menu: hip stability, ankle mobility, thoracic rotation, and shoulder external rotation work. Those minutes helped prevent the chronic overload that ruins youth development.

- Recovery as a skill. Players scheduled sleep windows, hydration plans, and post-session work with physio. It sounds simple, but most juniors skip it. At Equelite, recovery windows were part of the timetable, which meant they actually happened.

The on-site model kept the athlete’s circle tight. When something felt off, coach, trainer, and physio could meet in minutes. Small problems stayed small.

The Challenger choice: competition that hardens edges

Plenty of juniors are good in practice. The jump comes when the match schedule forces those habits to survive travel, different balls, and opponent variety. Alcaraz’s team emphasized a Challenger-heavy calendar in 2020. He captured three Challenger titles at 17 and posted a dominant win rate, a choice that earned him Newcomer of the Year and accelerated his ranking climb. The ATP summarized that stretch in its ATP 2020 newcomer article.

Notice the logic. Challengers offer dense learning at low glamour. Fields are uneven, which forces quick tactical adjustments. Courts and balls change week to week. You meet veterans who will not hand you anything. A teenager cannot fake it through that circuit. He either adapts or tumbles. Alcaraz adapted, fast.

Equelite also hosted a Challenger on its own grounds. That meant a young resident could play high-level pro matches in the same environment where he trained, then return to the gym and get treatment within the hour. The Academy removed friction and let the athlete pour energy into improvement. For a comparable example, see Tenis Kozerki’s on-campus Challenger.

From clay roots to multi-surface majors

A common myth says clay nurtures grinding and nothing else. Alcaraz’s path shows the opposite. The academy patterns emphasized first-strike tennis with balance. Serve placement mattered. Forehands on the rise mattered. Transition movement mattered. Those serve plus one and net instincts transferred cleanly to fast grass and mid-pace hard courts.

By the time he reached the tour’s top tier, Alcaraz could win in three distinct ways. He could outlast you with depth and legs. He could outrun you from defense to offense. He could out-accelerate you from serve to forehand and knife through the court. That versatility traces back to the habits baked in at 15 through daily tempo and forward patterns, not just clay mileage.

What families can copy from the Equelite blueprint

You do not need to be a prodigy to use the same framework. Here are concrete, transferable steps.

When to go full-time at an academy

- Use performance triggers, not birthdays. A good threshold is repeated results in the top tier of your age group at regional or national events over two consecutive seasons, plus proof that match volume is capped by logistics at home. If a player consistently beats older competition and local options are tapped out, the environment is holding them back.

- Time the move during a growth lull. Big growth spurts change coordination and injury risk. If your child is mid-spurt, plan shorter stays or delay a full move until body control stabilizes. Ask for a movement screen and growth assessment from the academy’s fitness staff before committing.

- Start with a four to six week trial. Live the schedule. Test compatibility with coaches, school options, and housing. Look for feedback standards. If all you hear is praise, that is a red flag. You want specific, repeated cues that appear across coaches and sessions.

- Keep school flexible but real. Choose an on-site or partner school that handles travel and still holds the athlete accountable. Ask for weekly study hours and tutoring support built into the training day.

How to structure competition blocks

- Build four to six week blocks around a theme. Example: two weeks clay Challengers, one week training reload with extra serve plus one, two weeks hard Challengers. Insert a light week every third week to protect the body.

- Climb only when winning. The simplest rule is thirty-three percent. If your player is winning fewer than one in three matches in main draws at a level, stay put. When they pass fifty percent over a block, test the next level. Results drive promotion.

- Choose tournaments that align with skills you are building. If your theme is transition and net instincts, add events with quicker conditions or altitude. If your theme is physical resilience and shot tolerance, pick heavier clay stops.

- Treat travel like training. Lock sleep, hydration, and nutrition plans before the block begins. Pack two of everything important, including shoes and strings. Book arrival two days early to hit, lift, and acclimate before match day.

- Track two numbers that matter. First, percentage of points where your player hits the third ball inside the baseline. Second, first volley success after approach. Those capture whether your practice themes survive competition.

How to build a stable support team that actually bridges home base and the tour

- Assign clear lanes. One head coach owns the player’s long arc. One traveling coach handles day-to-day on the road. Strength and conditioning plus physio define the training loads and green-light or red-light the calendar. If two people own the same decision, no one owns it.

- Create a micro-meeting rhythm. Require a 15-minute video call after every match block with all three leads. Agenda: what traveled well, what broke, what to adjust next block. Keep a shared document with three bullet points per meeting.

- Standardize testing. Run the same movement and fitness screen every six to eight weeks and compare numbers, not feelings. That keeps the calendar honest and flags the need for deload weeks.

- Protect recovery windows. Add recovery appointments to the calendar with the same weight as practice. If your child often does not have time for physio or mobility, the schedule is already broken.

- Keep home touches alive. The player should spend periodic weeks back at base to reset technique, strength, and sleep. That is where big technical changes are made. The road is for execution, not overhauls.

What Equelite gets right about environment

Environment scales performance. Equelite’s strengths are not fancy slogans. They are logistics and proximity.

- Multi-surface access in one place. Clay, hard, and a grass court allow pattern transfer rather than surface shock.

- On-site school and housing remove commute friction. A teenager can train, study, nap, and return to court without wasting hours in transit.

- Physio, strength coaches, and tennis coaches share a hallway. When a shoulder pinches or a knee nags, the team meets the same day and edits both the practice plan and the gym work.

- A Challenger tournament on campus gives residents a first taste of pro reality without the chaos of travel. That lowers the barrier to entry and speeds up learning.

Add it up and you get a system built for throughput. More quality reps, better recovery, faster feedback. That is how a 15-year-old’s tools become tour weapons.

The coaching change as a reminder, not a contradiction

The Ferrero split is a headline. The method is the story. Whether led by Ferrero or by another coach, the core operating system that formed Alcaraz endures. High-tempo patterns, a bias to finish at the net, and integrated physical care do not belong to a single person. They belong to a culture. Families can borrow that culture today.

A quick checklist families can print

- Does the academy measure tempo and decision speed, or does it only count winners.

- Can your player explain two patterns they are rehearsing this week and why they matter.

- Are recovery blocks on the written schedule, and are they supervised.

- Does the competitive calendar have themes, checkpoints, and light weeks.

- Are roles clear between the head coach, traveling coach, and fitness plus physio, with set meeting times.

If you cannot answer yes to most of those, change the plan before you change the coach.

The through line from Murcia to Villena to majors

Alcaraz’s story is not an overnight miracle. It is a series of deliberate choices. Leave home at 15 to find an environment that multiplies training quality. Normalize high tempo and forward movement. Use Challengers to test those habits against hard adults. Keep the body available through consistent prehab, sleep, and recovery. Then repeat. A fresh chapter begins after the 2025 split, but the blueprint holds. For players and parents, that is the most useful part of the story. You can adopt the blueprint right now, court by court, block by block, and let the method do the heavy lifting.