How Elite Tennis Center in Cannes Forged Daniil Medvedev

A teenager leaves Moscow for a smaller room with a bigger view

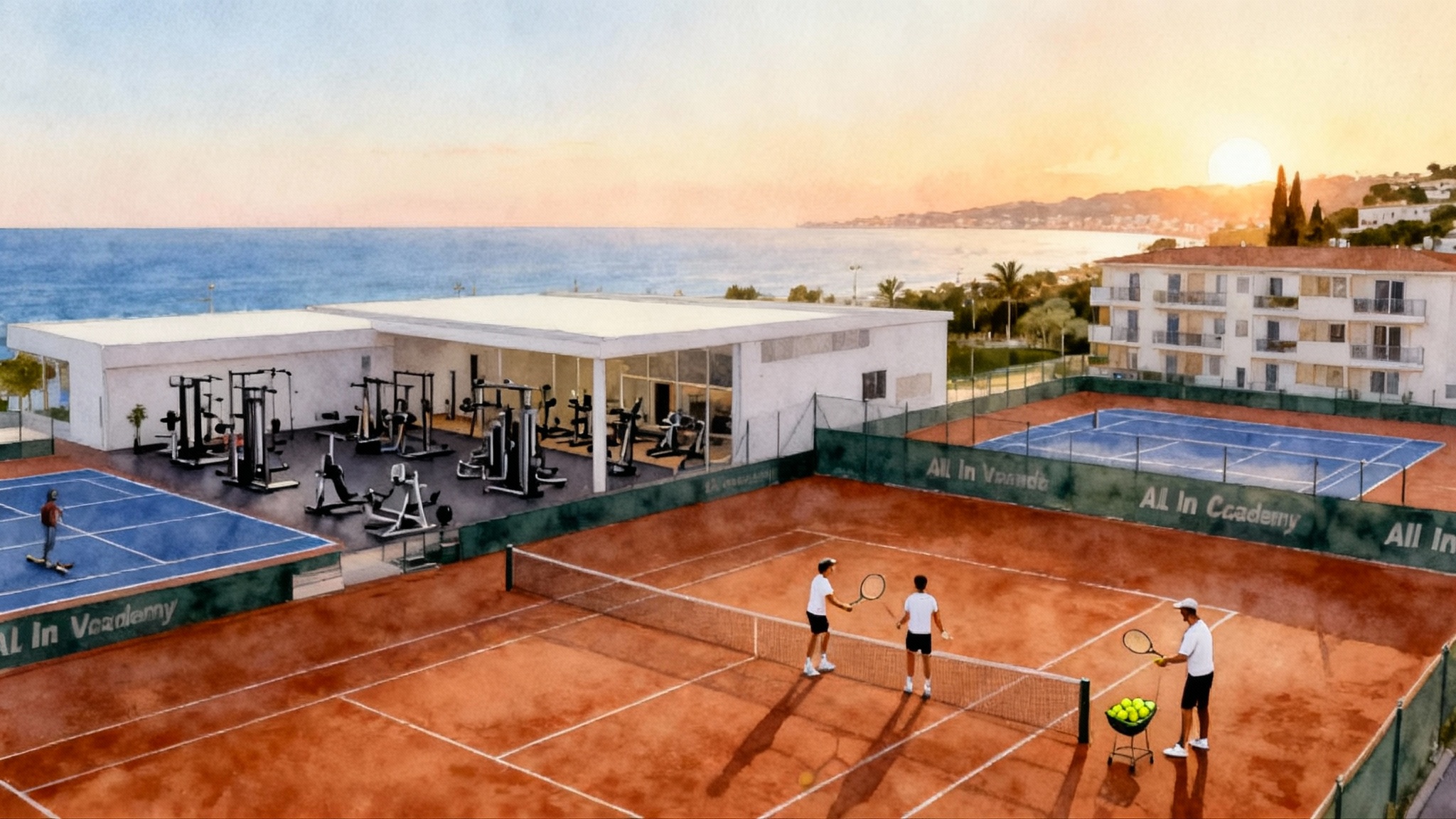

Daniil Medvedev did not choose the loudest academy or the most glamorous campus when he left Moscow as a teenager. He chose a smaller room with a bigger view. That room sat in Cannes, inside Jean René Lisnard and Gilles Cervara’s Elite Tennis Center. The decision traded fast‑paced visibility for deliberate attention. It replaced the comfort of a big brand with the discomfort of real accountability. There were fewer courts, fewer classmates, and far fewer excuses. Nearby options like All In Academy on the Riviera show the region’s depth, but Medvedev’s choice was different in scale and focus.

For many families, relocation feels like a binary choice. Stay home and save, or leap to a mega campus and hope scale produces excellence. Medvedev’s path shows a third option. Move to a boutique program where the player will never be anonymous, where the head coaches actually watch how a backhand breaks down after long rallies, and where the fitness coach knows the player’s feet as well as the physio knows his shoulder. In Cannes, the promise was simple. You will be seen.

Inside Elite Tennis Center’s small‑cohort design

Elite Tennis Center does not sell scale. It sells fit. The core idea is that a small roster lets coaches stack daily details into a steady identity rather than chase highlights that do not last. That design looks ordinary on paper and very different in practice:

- Small court groups: A player’s habits cannot hide. If a second serve drifts short under pressure, it shows up in every drill and every live point.

- Technical into physical: Footwork patterns and strength sessions are planned as a pair. The fitness coach does not guess what the tennis coach emphasized. The staff meets, plans, and repeats.

- Video next to the plan: Match notes live beside the training block. If a player loses return games in a specific pattern, the next day’s basket work mirrors that pattern.

The small‑cohort model gives time for cause and effect to be traced. That is the currency of development. With fewer players, the staff can build a feedback loop that closes quickly. Instead of a once‑a‑month review, every session can be a review.

Two coaches, one voice: Lisnard and Cervara

Big academies often impress with lists of names. Elite Tennis Center impressed by how two names worked as one. Jean René Lisnard set standards and structure. Gilles Cervara became the daily translator of those standards, first in practice blocks and then on the road. That continuity mattered more than any shiny facility.

Think of it like a good doubles team. Lisnard’s role set the geometry of the project: training blocks, intensity maps, tactical pathways. Cervara’s role tracked the live rally that is a season. He traveled, he watched, he refined. Most important, he kept speaking the same language. When Cervara took the reins full time, Medvedev did not switch languages. The same cues worked in practice, in Challengers, in Masters events, and then in New York for a first Grand Slam title. Continuity scaled with the player.

The style Cannes carved, patiently

Medvedev does many things his own way. He stands deep on returns, he uses a flat backhand that knifes through the court, and he solves rallies with a mixture of patience and sudden pace. In a large group, such an unconventional style might get sanded down by generic drills. In Cannes, the staff leaned into it.

- Court position as a tool: Training toggled between deep return positions that buy time and surprise step‑ins that rush servers without warning.

- Flat backhand as a feature: Drills focused on finding height when the ball jumped above shoulder level, then cutting it flat when contact stayed waist high. The goal was to keep opponents off balance rather than paint the lines.

- Serve patterns like a menu: The first and second serve aimed to start rallies in spots that matched Medvedev’s preferred exchanges. Wide on the deuce court to open a backhand, body on the ad court to draw a neutral ball, and sneak up the T when opponents began to lean.

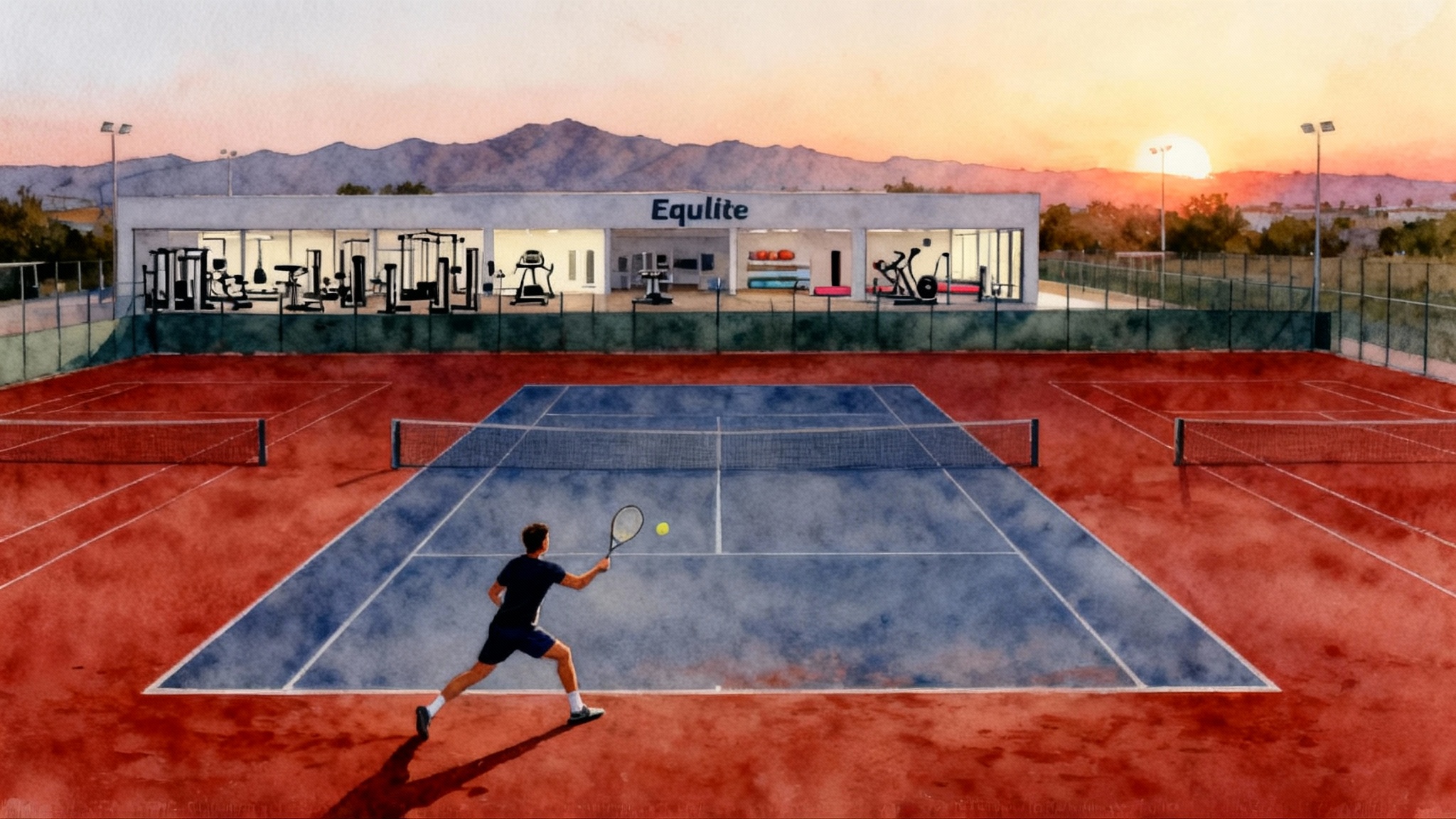

The academy’s integrated setup kept every department aligned with that identity. Strength sessions built the stamina to absorb deep court defending. Movement work emphasized elastic recovery from far behind the baseline. The physio plan assumed long exchanges on hard courts and the toll they take on hips and lower back. Nothing was random. Everything followed the same outline. We have seen a similar commitment to identity in Spain with how Equelite built Carlos Alcaraz.

From quiet gains to public wins

Results do not announce themselves with trumpets. They whisper for months, then shout in a single week. In Medvedev’s case, you could hear the whispers in cleaner holds of serve, fewer clusters of double faults, and smarter return games where he leaned on patterns instead of guesses. The shouts came later. A stretch of summer hard‑court tennis that turned him from a contender into a fixture, an end‑of‑season title against the best in the world, and finally a major trophy in New York that validated the long bet on continuity.

What mattered most was not the trophy list. It was the mechanism behind it. Small groups created clarity. Integrated planning carried that clarity from practice court to stadium court. A traveling coach protected the language day after day, city after city. That is how Cannes scaled.

Why a boutique academy can beat a mega campus

A mega campus can offer more of almost everything. More courts, more gyms, more players. Yet marginal gains often come from the opposite of more. A boutique academy can beat a mega campus when:

- The player needs a clear identity, not a buffet. Fewer voices make it easier to choose and to commit.

- The parents want face time with the actual decision makers, not a rotating set of court coaches they just met.

- The player’s game is unusual. Unconventional styles thrive when drills are built around them rather than squeezed into a standard template.

- The calendar needs to be flexible. Small programs can shift practice hours, find local competition, or add recovery days without asking a committee.

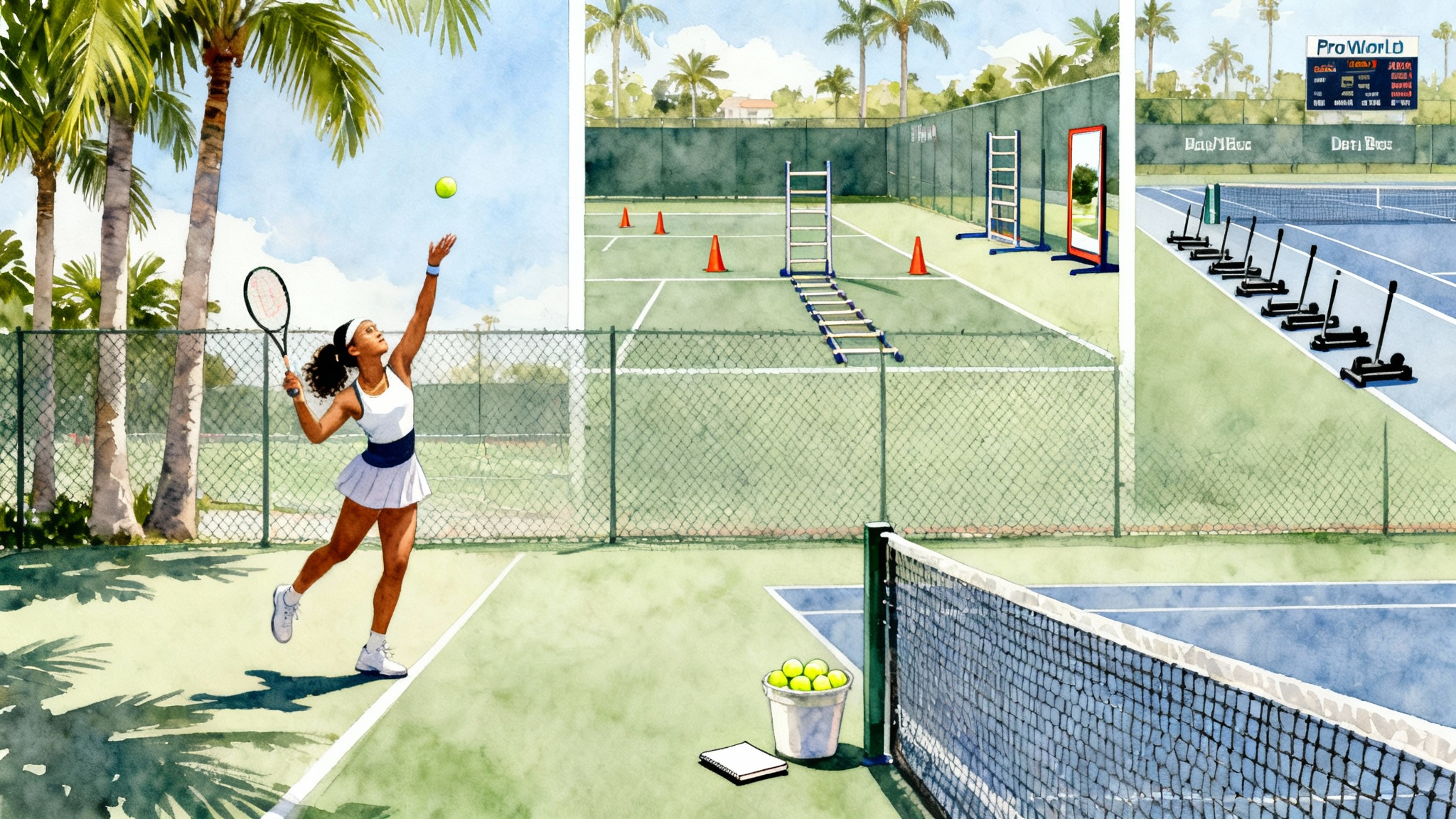

None of this says large academies cannot work. It says that for a certain kind of player, attention is a bigger lever than amenities. For a contrasting big‑campus pathway, explore how IMG Academy shaped Sebastian Korda.

The relocation decision: when to move, how to prepare

Relocating for tennis is a life decision with sport wrapped around it. Use this framework to think about timing and readiness.

- Technical stability: Move when two or three core strokes are stable enough to survive new input. A complete rebuild plus a new country can overwhelm a teenager.

- Competitive need: If the best weekly sparring at home fails to challenge your player, it might be time. Quality practice partners can be worth more than another local trophy.

- Language plan: Decide in advance how the player will learn and practice the local language. Schedule lessons before the move, then maintain immersion on site.

- School format: Map out school options that match the training block. Confirm exam windows and travel exceptions. The fewer surprises the better.

- Family logistics: Agree on a travel rotation for a parent or guardian during the first months. Emotional stability supports physical progress.

A good test is a three‑week trial block with clear goals. Track sleep, mood, ball quality in practice, and how fast the player blends in socially. If all four trend positive, the larger move stands a better chance.

Building a support team that travels

What Cannes showed is that the same voice needs to travel. Here is a blueprint families and academies can copy.

- Lead coach: One person owns the tactical identity. This person reviews match plans, runs pre‑match rehearsals, and leads video sessions after losses.

- Secondary or hitting coach: A second voice who can share load during long swings. This coach should echo the same language and cues.

- Fitness coach: Either on the road for key blocks or available daily by video. They should program to the tournament schedule, not around it.

- Physio: On site during Grand Slam and Masters weeks at minimum, with a remote plan for maintenance during smaller events.

- Data support: You do not need a full‑time analyst. A contractor who tags matches and produces simple pattern reports can raise match IQ quickly.

Contract structures matter. Families can book travel blocks in advance, such as a two‑event swing with fixed day rates and clear deliverables. After each swing, hold a review meeting and update the playbook.

The small‑group training week, modeled on Cannes

Use this sample week as a template. Adjust for age and workload.

- Monday: Technical morning on serve and first ball, fitness afternoon with acceleration and change of direction. Evening match clips focused on first‑serve patterns.

- Tuesday: Live points from deep return positions, then short‑court attacking from the baseline to train transitions. Mobility and hips in the gym. Ten minutes of breath work to close the day.

- Wednesday: Practice set with a stronger sparring partner. The weaker player starts each game 15 love up to script pressure. Heavy recovery in the afternoon.

- Thursday: Backhand height management. Drill low to high balls, then add mid‑court choices. Strength day with posterior chain emphasis for long rallies on hard courts.

- Friday: Serve and return rehearsal under time pressure. Use a serve clock and point the camera at the returner’s feet. Short video meeting to agree on match plan language.

- Saturday: Match play with constraints. For example, the player must hit at least one crosscourt backhand in every rally longer than five shots to reinforce patience before changing direction.

- Sunday: Off court. Walk, stretch, think about anything but tennis.

The point is not to copy drills line by line. It is to mimic the logic. Build each day so that the morning informs the afternoon, and the day informs the week. That is how small groups turn hours into identity.

How to interview an academy the Medvedev way

If you are choosing a training base, use questions that reveal process rather than sales points.

- Coach to player ratio: Ask for the average live ball ratio last month. Not the marketing ratio, the real one.

- Head coach presence: On how many days did the named leaders watch your court in the past four weeks for players at your level?

- Periodization example: Ask to see a written plan from a recent player, with names removed. Look for progression and rest days.

- Match review workflow: Who tags video, who writes the report, and who delivers it to the player? How long does it take after a loss?

- Travel policy: When the player competes, who goes, who stays, and how are decisions synchronized while on the road?

A strong program will answer these with specifics. A weak one will answer with slogans.

What parents and players can copy tomorrow

You do not need to live in Cannes to borrow its best ideas. Try these concrete steps.

- Create a one‑page identity: Write three bullet points that describe how you want to win points. Tape it to your bag. Review before practice and before matches.

- Standardize language: Pick a few cues for serve, return, and movement. Use the same words every time. Consistency beats cleverness.

- Film the feet: Point your phone at the feet for five minutes during returns and during first‑ball patterns. The feet tell you where the rally is going before the racket does.

- Track a single stat: Choose one, such as first serve plus one forehand made to a target. Count it every session for two weeks. Aim for a visible bump.

- Build a travel pack: Even if you compete locally, pack like you are on tour. Include recovery tools, a short menu of warm‑ups, and a post‑match checklist.

These habits create the same feedback loop that a boutique academy offers. Small, repeatable, aligned.

The long fuse to a Grand Slam

Grand Slam breakthroughs can look like explosions. They are usually long fuses. In Medvedev’s case, the fuse ran through Cannes, through quiet sessions where coaches cared about a single second‑serve pattern or a single movement cue, and through tournaments where a small traveling team spoke the same language in every hotel breakfast room.

This is not romance. It is process. Small cohort means you get noticed. Integrated planning means your body and your game move together. Coach continuity means your vocabulary does not change when the opponent does. Stack those three and you get something that travels. That is how you win in February, in June, and in September when the lights in New York feel brighter than any practice court.

Final takeaways for coaches and families

- Choose attention over scale when the player needs identity more than options.

- Move when your technical base can absorb change, your weekly sparring hits a ceiling, and your family has a language and school plan.

- Build a traveling staff that speaks one playbook and reviews it after every swing.

- Measure the small things that decide big matches, such as first‑serve plus one patterns and return depth under pressure.

Cannes did not gift Medvedev talent. It gave his talent a system. If you want a result that holds up against the world, choose a room where someone notices every habit that will matter under pressure. That is the lesson from a small academy on the French coast that helped a teenager grow into a player who could own the biggest court in the sport.